Happy 1600th birthday, Venice!

Sixteen centuries ago last week—25 March 421—the first stones of the Church of San Giacomo di Rialto (also known as San Giacometto), Venice’s oldest church, were said to have been laid, effectively founding the lagunar city that would go on to have such a formidable impact on the world as we know it.

The magnificence of Venice. Graevius, Johann Georg (1632-1703). Splendor Magnificentissimae Urbis Venetiarum Clarissimus; E Figuris elegantissimis, & accurata Descriptione emicans; In Duas Partes distributus.... Leiden, Peter Van der Aa, 1722.

See a complete description of this copy here.

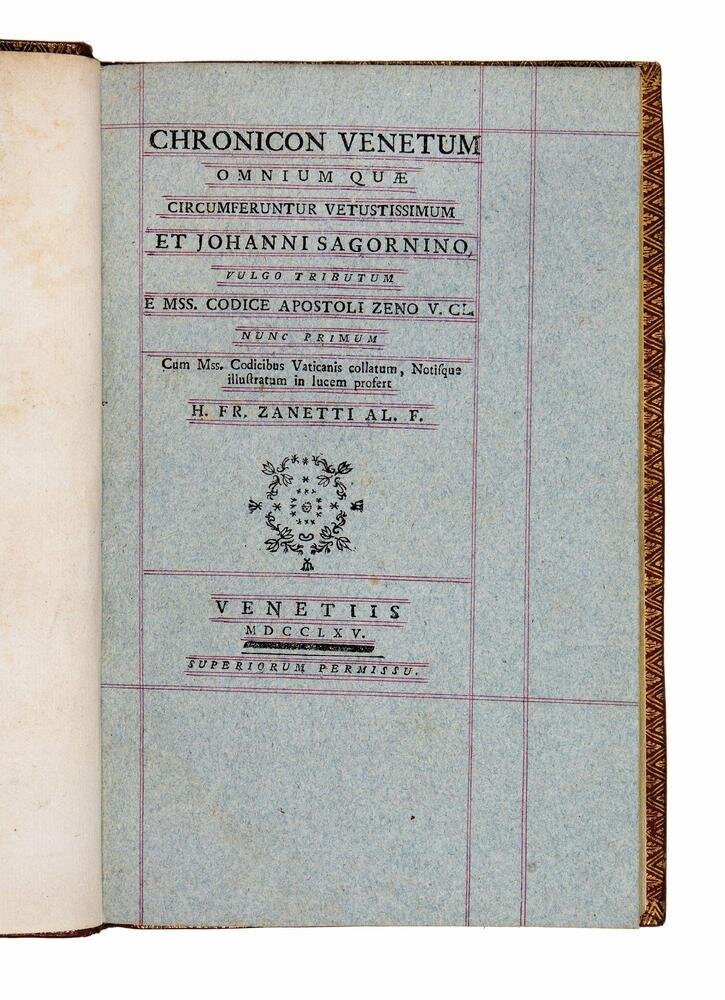

Already by the eleventh century, when the Chronicon Venetum—the oldest chronicle of the Republic of Venice, generally attributed to Ioannes Diaconus—was penned, Venice had become a major trading and maritime power. As attested by the luxury copy of the Chronicle printed on blue paper presented here, this trade position only grew stronger. Part of Venice’s commercial significance lay in its strong trading links to the East, and especially to the Ottoman Empire. This fact, mixed with the city’s thriving dye industry, meant that it was able to first introduce blue paper to the world of publishing (for more on this see the introduction to our Italian Books II catalogue, devoted to books printed on blue paper), a rich, visually appealing innovation that speaks to the elegance so characteristic of Venetian productions.

Ioannes, Diaconus (ca. 965-1018). Chronicon Venetum omnium quae circumferuntur vetustissimum et Johanni Sagornino vulgo tributum e Mss. codice Apostoli Zeno V.Cl. nunc primum Cum Mss. Codicibus Vaticanis collatum, Notisque illustratum in lucem profert. H. Fr. Zanetti Al. F. Venice, 1765.

See the complete description of this copy here.

Of course, many, many publishing “firsts” came out of Venice before blue paper, seeing as how the city was, as of the turn of the sixteenth century, the publishing capital of Italy, if not Europe. The same democratic, entrepreneurial, and cosmopolitan spirit that helped drive its commercial prowess also led to its centrality in the publishing industry following the arrival of the first press in 1469. The first privilege, of sorts, was granted that year to German typographer Johannes of Speyer, who was granted a five-year patent for printing in Venice and its dominions. This was more like a monopoly over the invention, however, with the first “real” authorial privilege being granted, also in Venice, in 1492, to Pietro Tomai for his Phoenix, in order to protect both his ‘invention’ and his book. Speyer’s death shortly after the privilege was granted meant the ‘invention’, and its commercial prospects, were once again fair game in La Serenissima. Others, like Erhard Ratdolt, of Augsburg, and Aldus Manutius, from Bassiano, thus moved into the city to establish their presses in the thriving milieu. In partnership with Bernhard Maler, also of Augsburg, and Peter Löslein, of Langencen (in Bavaria), Ratdolt published Regiomontanus’s Kalendarium in 1476 with the earliest known example of an ornamental title-page in the history of printing. It is also the first Italian book to feature extensive use of woodcut initials.

Regiomontanus, Johannes (1436-1476). Kalendarium. Venice, Bernhard Maler, Peter Loeslein and Erhard Ratdolt, 1476.

See the complete description of this copy here.

Manutius’s contributions are decidedly well known. In addition to specializing in Latin and Greek texts that were so critical to the development of humanist scholarship, his invention of italic type and the octavo “pocket-size” format meant that books could be more easily read away from the lectern. An example is presented here in a fine volume, housed in its contemporary binding, of the first Aldine edition of the Latin elegiac poets (generally published together following the Venetian princeps of 1472), followed by the first Aldus edition of Lucanus' Pharsalia, which first appeared in Rome in 1469.

Catullus, Gaius Valerius (ca. 84-ca. 54 BC) – Tibullus, Albius (ca. 55-19 BC) – Propertius, Sextus Aurelius (47-14 BC). Catullus. Tibullus. Propetius. Venice, Aldo Manuzio, January 1502. (bound with:) Lucanus, Marcus Anneus (35-65). Lucanus. Venice, Aldo Manuzio, April 1502.

See the complete description of this copy here.

Alessandro Paganini followed with his innovative long 24° format, as in his edition of the celebrated dialogue Asolani by the Venetian patrician and humanist Pietro Bembo, written between 1497 and 1504, printed by Paganini in Venice in 1515.

Bembo, Pietro (1470-1547). Gli Asolani di messer Pietro Bembo. Venice, Alessandro Paganini, April 1515.

See a complete description of this copy here.

Manutius’s brilliant design skills also led to such Renaissance masterpieces as the curious and enchanting Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a marvelous production that perfectly symbolizes the enduring attraction of the “Aldine anchor.”

Colonna, Francesco (ca. 1433-1527). La Hypnerotomachia di Poliphilo, cioe pugna d’amore in sogno. Dou’egli mostra, che tutte le cose humane non sono altro che Sogno: & doue narra molt’altre cose degne di cognitione. Venice, Sons of Aldo Manuzio, 1545.

See the complete description here.

But Manutius is still only one of the many important figures that made Venice the seat of their enterprise, and these are but some introductory points to the importance of Venice in the history of the book and to culture at large. So, in conjunction with this special anniversary of Venice’s 1600th birthday, we will be writing a series of blog posts that delve further into this infinitely large and important topic, our way of celebrating La Serenissima and her legacy to the history of the book.