Orlando in Venice: Giolito, Valgrisi, and the Market for a Modern Classic

Orlando Furioso, written by the Ferrarese poet Ludovico Ariosto (1474-1533), was a sixteenth-century bestseller that dramatically impacted the landscape of Italian literature and the print culture of Venice. The chivalric epic consists of 46 cantos of ottava rima that continue Matteo Maria Boiardo’s unfinished Orlando Innamorato (Orlando in Love), the first two books of which were published in 1482–3. This work followed the adventures of Rinaldo da Montalbano and his cousin, the heroic knight Orlando, who falls in love with the beautiful Angelica.

Boiardo, Matteo Maria (ca. 1441-1494).

Orlando innamorato. I tre libri dello innamoramento di Orlando di Mattheomaria Boiardo conte di Scandiano. Tratti dal suo fedelissimo essemplare. Nuouamente con somma diligenza reuisti, e castigati. Con molte stanze aggiunte del proprio auttore, quali gli mancauano. Insieme con gli altri tre Libri compidi.

Venice, Pietro Nicolini da Sabbio, March-April 1539.

Ariosto’s poem, which was published in its complete form in 1532, sees the Saracens and Christians at war in the days of Charlemagne, with Orlando going mad upon learning that Angelica has gone off with a young Moorish soldier. The epic unfolds across numerous episodes, including the restoration of Orlando’s sanity after Astolfo, an English knight, flies to the moon atop a winged horse (the hippogriff) to recover Orlando’s senses for him, and an interwoven narrative of the love affair between Ruggiero and Bradamante, a maiden warrior, sister of Rinaldo, whose marriage ultimately concludes the poem.

The epic is enthralling and, as it turns out, beloved by readers far and wide. Its success started already with the second version of the poem which was first published in 1521. This was reissued fifteen times (perhaps more), while the third (complete) version of the poem published in 1532 was republished sixteen times by 1540. Already greatly impacting the development of the Italian chivalric romance, after 1540, it was subsequently reprinted yearly, especially in Venice, where two Venetian printers in particular, Gabriel GioIito and Vincenzo Valgrisi, produced more editions of Orlando Furioso than any other printer.

Surely part of its appeal, the epic’s multiple viewpoints, lack of unified plot, and departure from “reality” also made it problematic for those who felt it strayed too far from the classical epics like the Odyssey and the Aeneid. With the contemporary desire to establish a recognizable tradition of Italian literature underway, this was a greatly contested issue, and part of the reason for Giolito’s success in particular was the way his editions effectively “legitimized the Furioso,” in the words of Daniel Javitch.

Titian, Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari, 1554. Public domain.

Gabriele Giolito de’ Ferrari (ca.1508-1578) printed his first Furioso in 1542. With it, he inaugurated the re-opening – following the death of his father Giovanni in 1541 – of his Venetian printing house all’insegna della Fenice (Bookshop of the Phoenix). Located in the Rialto district, the house specialized in modern and vernacular literature, and Orlando Furioso was to be the symbol of its greatness. We present here the rare Giolito 1546 quarto edition of Orlando, in an extraordinary blue-paper copy: one of the finest illustrated books produced in the Italian Cinquecento (see a complete description of this copy here).

The Giolito Furioso goes far beyond previous editions by other printers: for the first time the text of the poem is supplemented with commentary, and each canto is introduced by a woodcut vignette, as well as an argomento. Each of these paratexts asserts the poem’s “serious status and pedigree,” and the sentiment is underlined with Giolito’s dedicatory epistle, which opens the 1546 edition just as in that of 1542, to Henri II de Valois, then Dauphin de France, who had married Caterine de’ Medici in 1533. In this preliminary text the printer highlights the similarities between Ariosto’s poem – not merely a chivalric romance like any other – and the great ancient epics of Homer and Virgil.

The text was edited by the Venetian Lodovico Dolce (1508-1568), one of the closest collaborators of the Venetian house, and arguably one of the most important editors of modern literature operating in Venice in the next quarter century. In his Espositione di tutti i vocaboli et luoghi difficili, che nel Libro si trovano, which also supplements the text, Dolce highlights the didactic usefulness of the work as well as its moral value, a claim also made by Giolito in the dedicatory epistle and one which furthered the connection to the ancients.

The 1546 edition also includes – in response to the Cinque Canti first published in 1545 by the rival Aldine printing house – Giolito’s ‘novelty’, i.e., eighty-four stanzas dealing with the history of Italy, which he had in turn obtained from Ariosto’s son Virginio.

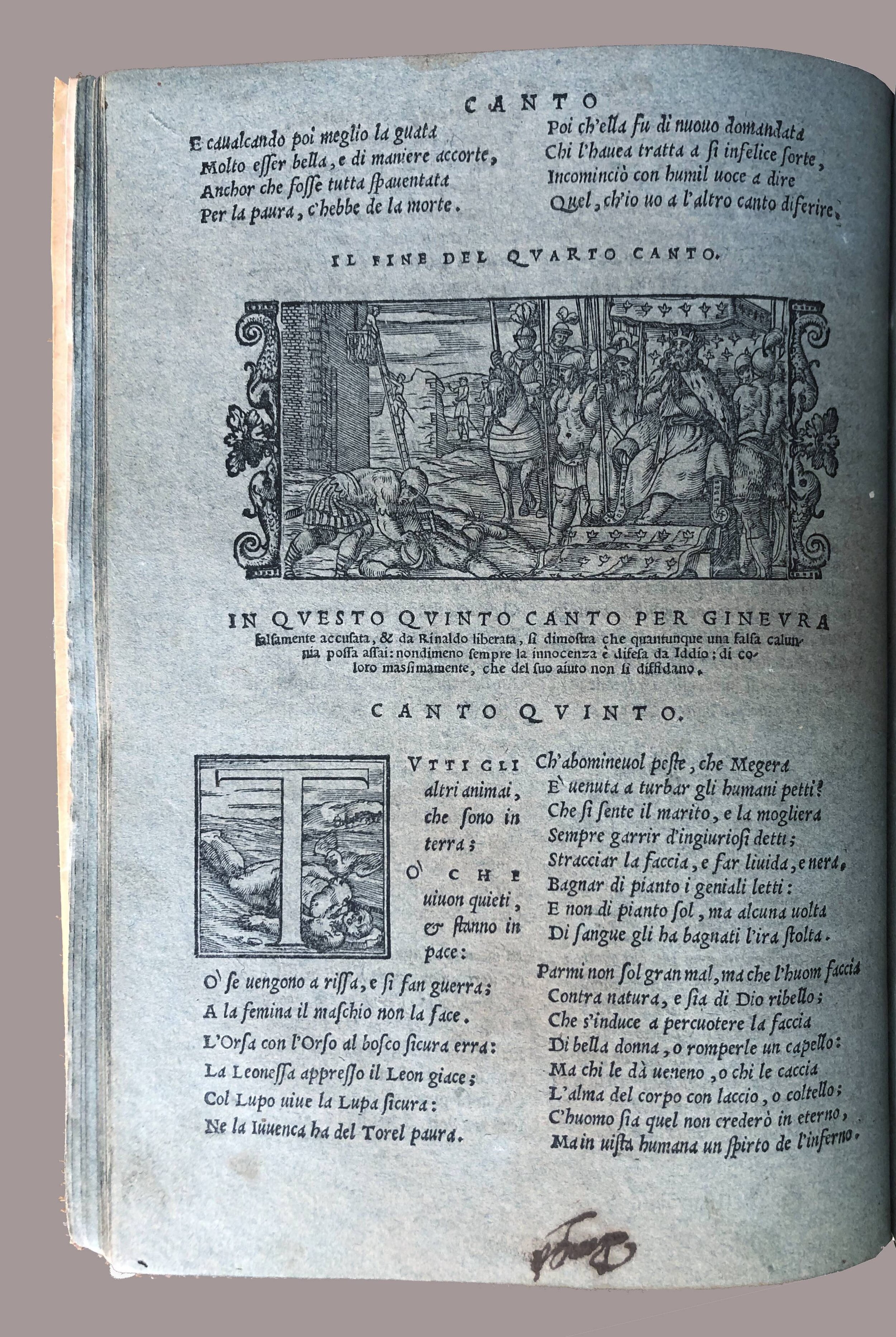

Another remarkable aspect of the Giolito Furioso is the illustrative apparatus that accompanies the cantos: forty-six woodcuts comprising a cycle whose stylistic quality, refined design, and abundance of detail represents a significant step in the illustration of the poem. Each vignette shows multiple scenes pertaining to the canto at hand, visually capturing the multifarious and ever-changing narrative structure of the poem. The various episodes diminish in size in the receding planes of the woodcut, and are thus conceived as separate but simultaneous actions: the majority of the vignettes depict two or three scenes from the related canto, although two woodcuts each include four episodes, and one – the vignette for Canto XLI with a surface area of only 47x87 mm – presents an incredible five scenes simultaneously.

The identity of the skilled artist or artists responsible for designing and cutting of the vignettes introducing each canto is as yet unknown; more recently the name of the Bolognese painter Jacopo Francia (1484-1557) has been offered, whereas a possible attribution to Giorgio Vasari is now generally refused. Indeed, Vasari cites the Giolito illustrations in his Vite, praising the “figure che Gabriel Giolito, stampatore de’ libri, mise negl’Orlandi Furiosi, perciò che furono condotte con bella maniera d’intaglio” (Vite, Florence 1568, II, part III, chap. 127).

In 1541, the Venetian Senate had granted a ten-year privilege for the woodblocks or ‘intagli novi’ of the Furioso, giving Giolito the exclusive right for using this illustrative apparatus. They were then re-used, with a few changes, in numerous subsequent editions issued by the Venetian printer until the quarto edition of 1559. They were also employed for illustrating the Discorso sopra tutti i primi canti d’Orlando Furioso by Laura Terracina, first published by him in 1549, and deeply influenced the diffusion, in the 1540s, of fresco cycles inspired by the figures and plots presented by Ariosto.

The 1546 Giolitina is further enriched by a woodcut medallion portrait of Ariosto taken from a block first used for the Furioso of 1542 and accompanied here by a sonnet. The source is the profile portrait introduced by Niccolò Zoppino in his famous Furioso of 1530, and ultimately derived from Titian. The artist employed by Giolito re-interpreted this earlier portrait, transforming it into a classical bust of Ariosto dressed in a toga and crowned with a laurel wreath. This new iconography was an immediate success and was readily imitated by other printers.

The copy presented here is one of the few copies of Orlando printed by Giolito on blue paper, a format first introduced by Aldus Manutius in 1514, following oriental practices which were particularly widespread in Venice, given city’s strong trading links with the East, as well a thriving dye industry. Like his illustrious predecessor, Giolito used blue paper for volumes he considered exceptional and evidently commissioned by distinguished clientele: blue paper was very special and represented a less expensive alternative to vellum.

Surviving Giolitine on blue paper are quite rare. An edition in carta turchina of the 1554 Furioso was sold in the Pinelli sale for 25 francs, and Angela Nuovo records copies on blue paper of the Giolito Furioso of 1543, 1544, 1549, 1551, and 1554. In this copy the Furioso of 1546 is supplemented by Dolce’s Espositione from the reprint of 1547. Copies of the Furioso of 1546 and 1547 printed on blue paper are unrecorded. Giolito continued to re-issue his Furioso, often changing the dates on the title-pages during printing in order to re-present unsold copies back on the market, or inserting quires from other issues. The interior composition of this volume may therefore testify to hectic phases in the production and ‘packaging’ of a copy on blue paper commissioned by a rich but impatient customer, as well as the aim to supplement the text of the poem with a ‘new’ version of the Espositione, which – as stated on the title-page, dated 1547 – is now corrected and enlarged.

The success of Giolito’s innovative publication was immediate and unprecedented, and the Furioso became a stand-in for the printing house itself. From 1542 onwards the poem was constantly re-issued, both in quarto and, as of 1543, in the cheaper and more popular octavo format, thus proclaiming Giolito’s success as a printer and businessman, and transforming the Furioso into a ‘classic’ of modern literature. So effective was his enterprise that “even when other Venetian publishers such as Valvassori and Valgrisi began to produce rival editions in the 1550s,” Javitch observes, “they continued to imitate the basic format that Giolito had introduced in 1542” (D. Javitch, Proclaiming a Classic, p. 31).

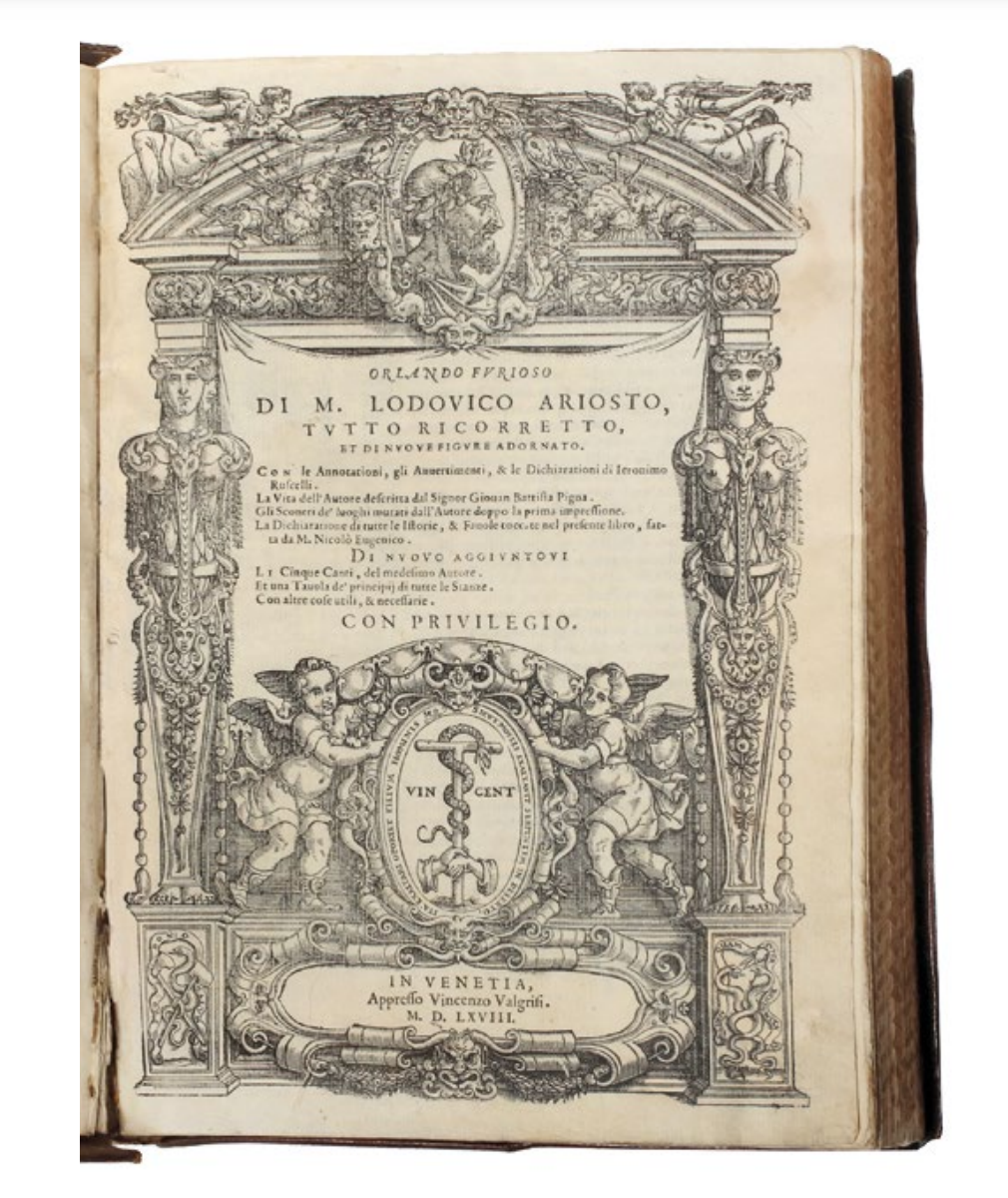

This is not to say that the contributions of these publishers did not further develop the publication of Ariosto’s poem as a masterpiece of Italian literature. Indeed, the Venetian printer Vincenzo Valgrisi produced more editions of Ariosto's poem than any other publisher, apart from Giolito himself, furthering the paratextual features introduced by Giolito as well as the illustrative apparatus. Valgrisi printed his first Furioso in 1556 and went on to produce seventeen editions up to 1587, as well as a less costly octavo edition.

But economy was not the issue for the owner of the handsome and rare quarto edition of 1568 presented here, which is housed in an exceptional Venetian binding of Mamluk inspiration, another hallmark of the Eastern influence that helped forge the distinctive character of Venice’s book trade.

This edition was edited for Valgrisi by the well-known poligrafo Girolamo Ruscelli (1504-1566). Ruscelli began work on a new Orlando between 1552 and 1553, basing his editorial work on the text printed by Giolito in 1552, which he claimed to have compared with previous editions from the 1530s, as well as some autograph corrections received by Ariosto's brother Galasso. His philological ambition, and the textual accuracy employed, are already declared on the title-page: the Furioso is now “tutto ricorretto”, and in polemic against Lodovico Dolce Ruscelli “sought to rival him as the editorial custodian of Ariosto’s poem” (Javitch, p. 39). The poem is supplemented with new commentaries and paratexts, including Ruscelli’s Annotationi, et Avvertimenti sopra i luoghi importanti del Furioso, mainly taken from the compendium published by Tullio Fausto da Longiano in 1542, and the Raccolto di molti luoghi, tolti et felicemente imitati in più autori, dall’Ariosto nel Furioso, in which Ruscelli substantially pirated the Espositione composed by Dolce for Giolito, quoting the names of other commentators but never that of his great and fierce rival.

Starting with the Furioso of 1565, Valgrisi added the texts of the Cinque Canti, allegorical prose, and argumenti by Luigi Groto from Adria (1541-1585). From the edition issued in 1560, the poem is also further accompanied by an enlarged version of Ariosto's Vita, composed by the secretary of the Estense court and minister of Alfonso II Giovanni Battista Pigna (1529-1575) and originally published in his treatise I Romanzi (1554). In the Vita Pigna apparently refers to a Titian portrait – “egli di mano dell’eccellentissimo Titiano pare che ancor sia vivo” – that could be the source of the block designed for the Zoppino Furioso of 1536, then re-interpreted by Giolito as a laureate classical poet, and now included again, in reverse form, by Valgrisi in the rich architectural title-border that opens the volume.

In addition to including “Giolito’s” medallion portrait of Ariosto in reverse, the Valgrisi Furioso offers one of the finest examples of multi-narrative book illustration, with the first full-page woodcuts for each canto of Ariosto's masterpiece, all newly designed. Each woodcut, framed within fine borders with figures and grotesques, records one or more scenes from the illustrated canto, rendered with a skilful use of perspective and close attention to the iconographic tradition established by Giolito.

In the nineteenth century, Girolamo Baruffaldi ascribed the designs for these woodcuts to the Ferrarese painter Dosso Dossi (1480-1542), while Paul Kristeller later attributed them to his brother Battista Dossi (1517-1548), owing to the latter's stylistic tendencies. Recently, Battista's name has been proposed again, along with that of an artist belonging to the circle of Giovanni Britto. A further innovative feature of the Valgrisi cycle is the introduction of geographic charts as backgrounds for the multiple plots of the poem: an apt visual representation of that geographical space which Ariosto continuously enlarged in the Furioso, ultimately including, in the definitive edition of 1532, important discoveries of the navigators of his time. The marvellous woodblocks continued to be re-used in subsequent editions issued from Valgrisi's printing house up until 1603.

One of the greatest points of interest of this copy lies in its spectacular contemporary morocco binding of Islamic inspiration, evidently originating in Venice where it was commissioned by its unknown but surely distinguished and affluent first owner. The binding offers striking testimony to the Ottoman influence on Venetian craftsmen who were active in the field, an influence that can be traced until the end of the sixteenth century. The debt is evident in the great elaborateness of its decoration and ornamental gilt motifs, akin to contemporary patterning in the decorative arts or embroidery designs: the 'moresque' or Mamluk interlaced scroll, the central medallion, the sumptuously gauffered gilt edges in geometric patterning, the extended yapp edges. Some ducal Commissioni – i.e., official documents signed by the Doges or by the Procurators and granted to Venetian patricians elected to the highest offices – exhibit similarly gilt-tooled covers. Tammaro De Marinis argues that these Islamic-style bindings – including those bindings with polychrome filigree decorations – could be the result of a collaboration between Persian and Venetian binders: “there is however no archival evidence of the existence of Persian crafstmen in Venice at the time” (A. Hobson, “Islamic Influence on Venetian Renaissance Bookbinding”, p. 114).

In the early 1900s, this copy was owned by the outstanding American bibliophile Robert Hoe, a founder of the Grolier Club, as well as its first president. As stated in the foreword to the sale catalogue of his marvellous collection, “he was a lover of fine bindings, and his library is rich in specimens of the work of all the great binders, ancient and modern”.

The exquisite binding presented here further reveals the great appeal of the Furioso and the wide range of its readership throughout the Cinquecento. As a result of this popularity, the poem was offered on the market in various forms, from the less expensive octavo format to the wide-margined and lavishly illustrated editions. The Furioso was the most widely diffused work in Venetian homes, and it could be bound in plain limp vellum or housed within deluxe bindings, as is the case with the present copy: it thus made its way into the hands of every rank of reader, small, middle or great.

How to cite this information

Julia Stimac and Margherita Palumbo, "Orlando in Venice: Giolito, Valgrisi, and the Market for a Modern Classic," 14 April 2021, www.prphbooks.com/blog/orlando. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.