Giambattista and Giandomenico Tiepolo: The Real Otherworldliness of Two Rococo Masters

This year marks 250 years since the death of rococo master Giovanni Battista (Giambattista) Tiepolo (1696–1770), arguably the most celebrated artist of 18th-century Europe. In his honour, this post considers the work of not just the elder Tiepolo, but also that of his son Giovanni Domenico (Giandomenico; 1727–1804), through whom the changing tides of the 18th century most clearly come into focus. Between Baroque and Neo-classicism, this was a fascinating moment in the use and status of art as the Western world entered a period of intellectual, social, and political upheaval, that would culminate with the French Revolution in 1789 and the fall of the Venetian Republic not a decade later.

Giandomenico Tiepolo, The Tiepolo Family. Photo: Sotheby’s (PD-Art photographs).

Originating from Venice, the Tiepolos were critical in bringing the lagunar town back into artistic prominence during the 18th century. In its golden age two centuries earlier, Venice had been a major artistic centre, but its importance had since fallen off as artists like Caravaggio and the Carracci brothers shifted the focus to central Italy, especially Rome. In the 18th century, the age of the Grand Tour, artists like Canaletto, with his famous Vedute or views of the city, capitalized on the tourist market and helped revive Venice as an important artistic centre, despite the city’s waning political significance. This vedute tradition was carried on in the next generation by Francesco Guardi (1712–1793), who traded Canaletto’s prized accuracy for the freedom of imagination. However, it was the Tiepolos, Giambattista in particular, who transformed the city’s interiors, painting such massive dramatic scenes like the Capture of Carthage, his first masterpiece, executed in 1728–29 as part of the scenes of Roman history that decorated the Ca'Dolfin (the house of the Dolfin family). In fact, Giambattista married into the artistic family of Francesco Guardi when he wed the latter’s sister Cecilia (1702/3-ca. 1779; their brothers Giovanni Antonio and Niccolò Guardi were also artists, as was the father, Domenico), with whom he had nine children, including Giandomenico.

Canaletto, The Portico with the Lantern, from a spectacular wide-margined and complete set of his etchings, in a contemporary binding, together with a series by Marieschi.

Canaletto, Antonio Canal called (1697-1768). Vedute Altre prese da i Luoghi altre ideate... [Venice, Giambattista Pasquali, after June 1744]. (bound with:) Marieschi, Michele (1710-1743). Magnificentiores selectioresque Urbis Venetiarum prospectus... Venice, at the author’s atelier, 1741.

See the complete description here.

Giambattista Tiepolo, The Capture of Carthage, 1728-29. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Between the 1720s and 1770, the Tiepolos dominated the art scene with magnificent scopic confections that merged the world of imagination and fantasy with those of mythical heroes, ancient history, and divine splendor. Like a stage set with dazzling perspective, these highly inventive works are grandiose and theatrical but with such a high degree of detail and finesse that they also seem incredibly delicate, almost fragile. Importantly, their quality of staged fiction also works to bring the viewer in, inviting her participation on a purely imaginative level.

It is no coincidence that books printed on blue paper—a lavish option that was still more affordable than vellum—flourished at this time, as evinced in the latest installment of our Italian Books series: markers of luxury and wealth were increasingly varied and available, at least for those of the right class. Most visibly in France, this was a period when the power shifted from the monarchy to the aristocracy, putting the fancies of the leisure class, with their enormous wealth and political power, flagrantly on show. In Venice, the masks of Carnevale were worn half the year and decadent festivities were de rigueur. This was the basis of Antoine Watteau’s paintings of Venetian of splendor, as with his the Fêtes Vénitiennes of 1719. Rococo art presented the luxury and excess of this aristocratic class with visual delicacies that only too recently had been reserved for the ruling sect.

Rome versus Bologna. A defence of Raphael and Carracci printed on blue paper.

Victoria, Vicente (1658-1712). Osseruazioni sopra il libro della Felsina pittrice per la difesa di Raffaello da Urbino, dei Caracci, e della loro scuola.... Rome, Gaetano Zenobi, 1703.

See the full description here.

Antoine Watteau, Fêtes Vénitiennes, 1719. National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh.

A response to the classicism and the “Grand Manner” of Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), rococo art originated in France with lighthearted scenes of frolicking aristocrats rendered with loose brushwork and sugary pastels. In Italy, it was Giambattista Tiepolo’s name that became synonymous with the style: his luminous, chromatically brilliant works, often rendered with complementary pastel colours, are imbued with a soft, romantic quality and lively, animated scenes. However, they also differ from the French example with more dramatic subject matter taken from history, myth, and literature. Significantly, he also continued the Baroque tradition of ceiling decoration, which came to form one of the most important elements of his artistic legacy.

In 1750, Giambattista brought his sons Giandomenico and Lorenzo (1736-1776) with him to Würzburg, Germany, where he had been invited by the Prince Bishop Carl Philipp von Greiffenklau and commissioned to paint the Imperial Hall of the Neue Residenz (the royal residence). Between 1750 and 1753, the Tiepolos completed the grand ceiling fresco Olympus and the Four Continents. Having studied under his father, Giandomenico demonstrated his precociousness early on, and at just 13 years old he became the elder Tiepolo’s chief assistant. In 1750, he was a mere 23 years of age, but he nonetheless collaborated with his father so successfully on the Residenz ceiling fresco that it is often difficult to discern their individual contributions.

Giambattista and Giandomenico Tiepolo, Olympus and the Four Continents (1750—1753), (Residenz Palace, Würzburg, Germany). Photo: Maria (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The elaborate allegorical fresco places Apollo presiding over the planets and continents, the four parts of the world then known—Europe, Asia, Africa, and America—which are placed at each side of the room. The ceiling, a testament to the range of the Tiepolos’ subject matter, is particularly impressive for its changes in perspective, designed to correlate with the view of palace visitors as they stopped at certain designated points along the grand stairway. It also evinces a trademark of the Tiepolos’ art, its “sprezzatura”—a studied effortlessness first described in Baldassare Castiglione’s Il libro del cortegiano as a type of nonchalance cultivated to conceal all art and industry.

Title page from the extremely rare Cortegiano.

Baldassarre Castiglione (1478-1529). Il libro del cortegiano del conte Baldesar Gastiglione [sic]. Florence, Benedetto Giunti, 1531 [probably Rome, 1537].

See a complete description of this copy here.

Upon their return from Würzburg, Giambattista purchased a small family villa in Zianigo, near Mirano, which Giandomenico would decorate with frescoes between 1759 and 1797. These are fascinating works, not only for their execution, but also in terms of subject matter, since the artist, unconstrained from the wishes of a patron, permitted himself absolute freedom. In 1906, nearly all the frescoes were stripped from the villa to be sold abroad; however, they were purchased by Venice in 1936 and moved to the Ca’ Rezzonico Museum on the Grand Canal, where they are now on view in small rooms, in an arrangement closely recalling their placement in the family villa.

The reason for the extended period of their execution is largely due to the Tiepolos’ commissions, which were often quite extensive projects. For example, in 1762, they were called to paint the royal palace in Madrid, where they worked for the next eight years on several large frescoes and altarpieces. These works are said to have exerted an important influence on a young Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828). Although Goya’s famously dark scenes may seem at odds with the Tiepolos’ brighter aesthetic, the radical freedom of imagination is entirely evident in both oeuvres. Indeed, an exciting exhibition curated by Dr. Sandra Pisot at the Hamburger Kunsthalle, “Goya, Fragonard, Tiepolo: The Freedom of Imagination”—scheduled for 13 December 2019 to 13 April 2020 but sadly temporarily closed due to COVID-19—considers the Spanish and French artists along with Giambattista and Giandomenico Tiepolo as important champions of an innovative formal language and important precursors to modernism.

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, Una Reina de Crico (Punctual Folly) 1816 - 1824 (printed 1877). Original etching with burnished aquatint engraved by the artist for Los Proverbios.

See the full description here.

Despite the similarities in the style and technique of Giambattista and Giandomenico Tiepolo, an important difference lies between them in terms of subject matter. The difference is markedly evident in their paintings from as early as the 1750s, for example in the decorative frescoes at the Villa Valmarana, the palatial residence of the aristocratic Valmarana family from Vicenza, which the Tiepolos carried out in 1757. There Tiepolo the father took on the main rooms of the villa while Giandomenico worked on the guest quarters, the ‘Foresteria’. In Giambattista’s “Room of Ariosto,” the artist painted scenes from Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, presenting the story of Angelica and Medoro. In these works, represented here by Angelica and Medoro with the Shepherds, the master’s ability to create alluring heroic-mythical scenes in an inviting though still otherworldly way is particularly salient in the idyllic pastoral setting and extreme animation of Angelica’s clothing.

Giambattista Tiepolo, Angelica and Medoro with the Shepherds, 1757.

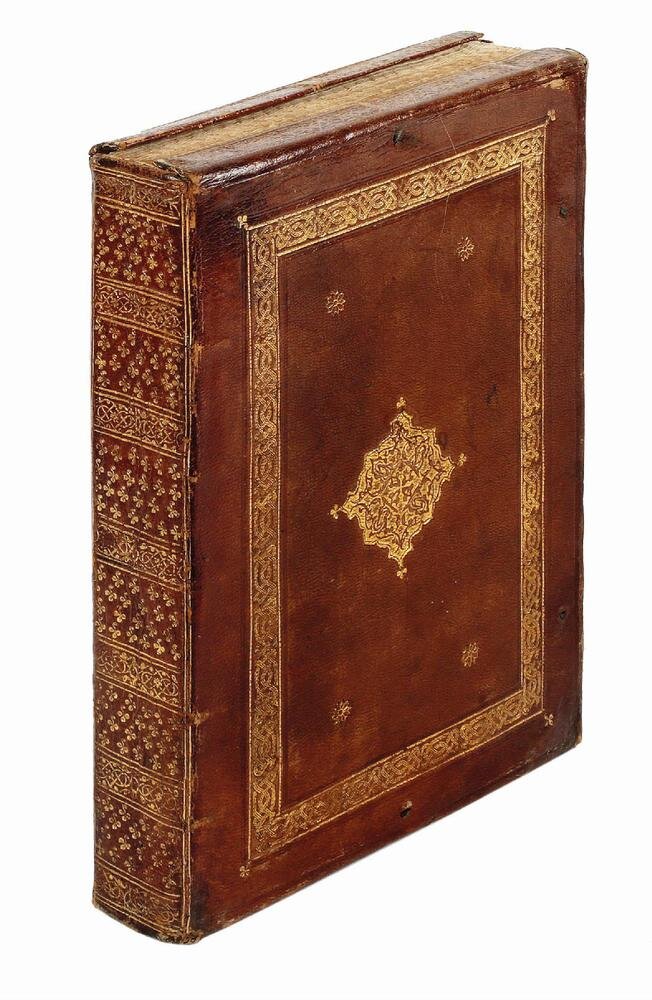

The Valgrisi Furioso, in a precious Islamic-style Venetian binding.

Ariosto, Ludovico (1474-1533). Orlando furioso... Di nuouo aggiuntoui Li Cinque Canti.... Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1568.

See the complete description here.

Giandomenico, meanwhile, painted his magnificent Il Mondo Novo—that is, the New World. This important work is organized around a small object, a box of wonders with eyeholes through which viewers could see printed, hand-coloured panorama views (vedute ottiche). Yet Giandomenico did not focus on the object itself; rather, he paints the backsides of the crowd of people gathered about it during carnival—real people, men and women from a diverse array of ages and classes, as would be found in contemporary Venetian streets, all bustling together as they seek to engage with this fascinating pictorial achievement.

Giandomenico Tiepolo, Mondo Novo, 1791. Detached Fresco. Museo del Settecento Veneziano, Ca' Rezzonico, Venice. Photo: PD-US.

This emphasis on contemporary life is a significant departure from his father’s work, with its expansive grandeur and fabricated universe: Giandomenico ultimately preferred to look at the world around him. Although he still painted numerous decorative compositions in the highly rococo manner of his father, Giandomenico particularly excelled at genre scenes of popular theatre and everyday life, which he rendered in a more objective, realist style, if still elegant and playful and with the exquisite lightness of touch inherited from the elder Tiepolo.

Il Mondo Novo was an important subject for the artist, who revisited it again many years later for the portego (vestibule) at the family villa in Zianigo. As evident in this fresco (pictured above), the scene involves another recurrent favourite of his: the Commedia dell’Arte character Pulcinella, who was even granted his own room at the villa, which the artist painted with enigmatic scenes involving many Pulcinella figures in a variety of situations.

[Commedia dell’Arte]. Album with representations of Italian, mainly Venetian, costumes and characters. Illuminated manuscript on parchment. Italy (Venice ?), first quarter of the 17th century.

See the complete description here.

Although hardly a “real” person, Pulcinella stands for the voice of the people and thus goes hand in hand with the “new world” Giandomenico held so dear. A crafty, scrappy, ambiguous, and versatile figure, he is also lazy, spirited, and greedy, silly and cruel. Ever the paradoxical figure, this diversity of traits combine for a fascinating representation of the more basic needs, wants, and wishes of society that were then coming into view. Witty and sarcastic, Pulcinella mocked the powerful while his double-sided, elusive character formed an apt representative of the tensions at play in European society, even if he was still completely fictitious.

In a series of 104 drawings titled “Divertimento per li regazzi” (“Fun for Kids”), Giandomenico represented the life story of Pulcinella right up until his death, further pressing the representational limits of this fictional being. In the image presented here, held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Pulcinella is being buried while surrounded by a group of similar bystanders. As the museum description points out, “Both subject and composition allude to representations of saints' burials, imparting sacred overtones to the scene and emphasizing Punchinello's role as a secular everyman.” A far cry indeed from his father’s more grandiose figures.

Giandomenico, The Burial of Punchinello, ca. 1800

As so often happens, a great hint at the divergence between father and son is evident even earlier, in the medium of printmaking, which affords a special haven for experimentation.

The first etchings Giandomenico executed were the Stations of the Cross, after the paintings he had produced for the Venetian church of San Polo (1748-1749), the composition and style of execution of which were greatly influenced by his father.

However, during their shared time in Würzburg between 1750 and 1753, the younger Tiepolo undertook a series of etchings that would come to be regarded as one of the most original and inventive cycles in the history of printmaking. Although the idea for the Idee pittoresche sopra la Fugga in Egitto (Picturesque Ideas on the Flight into Egypt) is said to have come from the elder Tiepolo (who painted a version of it, pictured at right, near the end of his life), Giandomenico ran with it, using it to prove his artistic inventiveness and defend his own artistic reputation (even if this were ultimately to remain overshadowed by that of his father).

Giambattista Tiepolo, The Flight into Egypt, ca. 1767-70. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

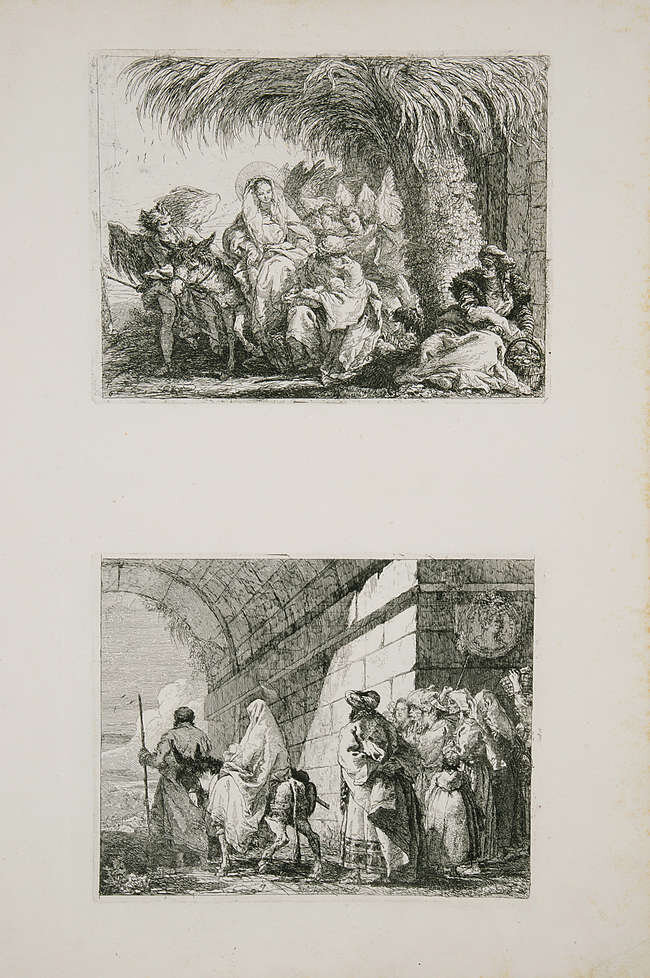

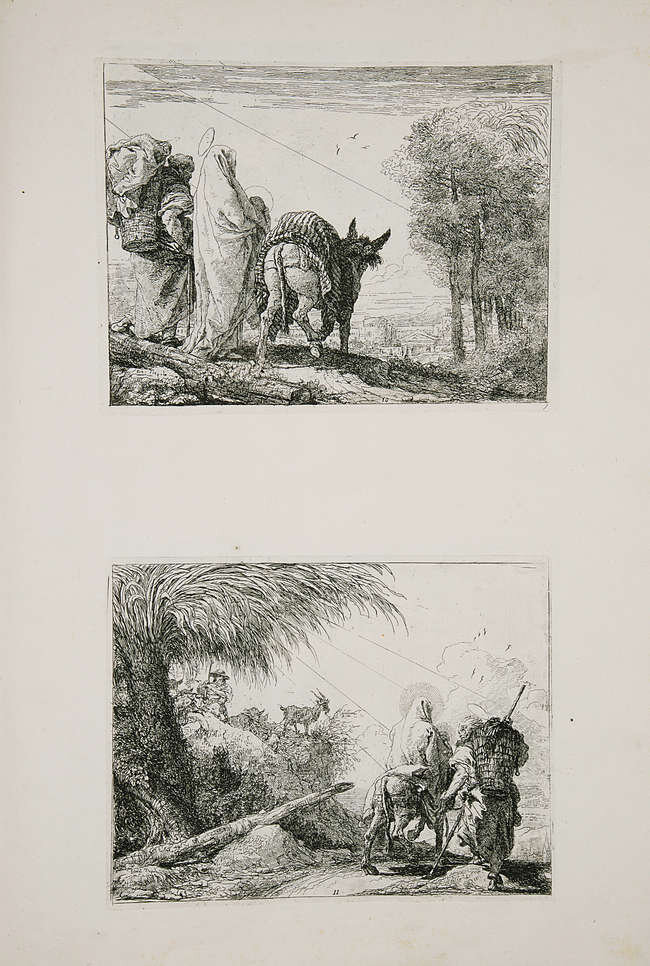

The example of the celebrated series presented here features the plates in their final state (see the full description here). As briefly recounted in the Gospel of Matthew, when an angel had warned them that King Herod intended to find and kill the infant Jesus, Mary and Joseph fled with their son to Egypt. With great technical variety, the series depicts the Holy Family on their journey from Palestine to Egypt and back.

Title leaf from Giandomenico Tiepolo, Idee pittoresche sopra la Fugga in Egitto. [1753].

Giandomenico Tiepolo, Mary helped by an Angel and Joseph carrying the basket and Mary helped by two Angels follows Joseph with the donkey (1753), from Idee pittoresche sopra la Fugga in Egitto. [1753].

The subject itself was not unusual for artists, and Martin Schongauer and Albrecht Dürer had long made it particularly popular among printmakers. However, The Flight into Egypt is a simple, two-stage story and had generally been treated as such. The young Tiepolo, however, transformed it into a magnificent series of 24 etchings which look fondly on the Holy Family along their arduous travels: with elegant rococo grace and clouds of angels, Giandomenico realizes a tender, almost cinematic portrayal that presents the Family as a family.

“The theme of the Holy Family had been rendered sterile by centuries of use [...] To give the subject a new aesthetic dignity, Giandomenico concentrated on details of landscape, such as trees, shrubs and views, and on domestic objects, which gave the episodes a feeling of truth, an ethical quality impregnated with poetry” (Rizzi, The Etchings of the Tiepolos, p. 18).

By turning the episode into a pictorial cycle, Tiepolo completely changed the handling of the Flight into Egypt: apart from the first and last images, which depict the departure from Bethlehem and arrival into Egypt, the etchings are basically interchangeable, such that images of the Holy Family, the angels, the donkey, and the landscape can be rearranged into dynamic, ever-changing compositions.

The series later became an important source of material for the monumental collection of drawings Giandomenico Tiepolo undertook for illustrating the New Testament; at least twenty-eight of the drawings focused on the Flight into Egypt.

* * *

Despite Giandomenico’s forward-looking perspective, already evident so early in his career, the Tieopolos were out of fashion by the time he finished the frescoes at Zianigo. The change had begun around the middle of the 18th century: influenced by recent scientific advancements, thinkers like Rousseau, Diderot, and Voltaire became figure heads of the Enlightenment, which brought a new emphasis on empiricism and sought to shed light on science and reason. This ushered in an age of rationality and equality that did away with the inherited traditions that continued to uphold the aristocracy.

The Tiepolos’ lightness and grace was considered immoral and exchanged for the hard severity of Neoclassicism. In 1796, Napoleon’s troops invaded Italy, and Giandomenico retired to his villa, taking with him what was left of the great Venetian painting tradition. In 1797, the Venetian Republic fell to Napoleon’s armies, and by 1799, the military leader had conquered most of Italy in the name of the French Revolution.

The great irony, of course, is that rococo was part of this shift, and the Tiepolos, though each fantastically otherworldly in their own way, were also each doing their part to to realize a new kind of art, one that would involve the viewer in a way that had previously been unimaginable.

C. Feller Ives, “Picturesque Ideas on the Flight into Egypt Etched by Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 29.1970/71 (1971), 5, pp. 195-202; A. Rizzi, The Etchings of the Tiepolos, London 1971, nos. 67-93; Tunick-Rizzi, Italian Prints of the 18th Century, London 1981, no. 11; A. M. Get - G. Knox, Domenico Tiepolo: A New Testament, Bloomington, Ind., 2006, p. 77; F. Reue, Giandomenico Tiepolo - Die Flucht nach Ägypten, Augustinermuseum Freiburg (exhibition catalogue), Freiburg i.B. 2007; Philobiblon, One Thousand Years of Bibliophily, no. 234; D. A. Spieth, “Giandomenico Tiepolo's 'Il Mondo Nuovo': Peep Shows and the ‘Politics of Nostalgia’”, The Art Bulletin 92.3 (September 2010), pp. 188-210.

How to cite this information

Julia Stimac, “Giambattista and Giandomenico Tiepolo: The Real Otherworldliness of Two Rococo Masters," 18 March 2020, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/tiepolo. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

![Title page from the extremely rare Cortegiano.Baldassarre Castiglione (1478-1529). Il libro del cortegiano del conte Baldesar Gastiglione [sic]. Florence, Benedetto Giunti, 1531 [probably Rome, 1537].See a complete description of this copy here.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1584579436587-SYNOPEKZKV19W1QIWWI7/castiglione%252Btitle%252Bpage.jpg)

![[Commedia dell’Arte]. Album with representations of Italian, mainly Venetian, costumes and characters. Illuminated manuscript on parchment. Italy (Venice ?), first quarter of the 17th century.See the complete description here.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1584566862263-6JQMDJC2886YTWEIY4CW/Commedia+dell%27arte++masquerade.jpg)

![Title leaf from Giandomenico Tiepolo, Idee pittoresche sopra la Fugga in Egitto. [1753].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1584571204095-EPYU8RJ1Z1GJNRLBU4E1/Tiepolo+14+title.jpg)

![Giandomenico Tiepolo, Mary helped by an Angel and Joseph carrying the basket and Mary helped by two Angels follows Joseph with the donkey (1753), from Idee pittoresche sopra la Fugga in Egitto. [1753].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1584571961812-4Q92SV6CGI9WF8IF7TNA/Tiepolo++2+2.jpg)