The New Patronage

From 14 February to 13 March 2022, the historic headquarters of the Italian Ministry of Economic Development in the Roman via Veneto – a building designed by the leading Italian architect Marcello Piacentini and inaugurated in 1932 – hosted the exhibition Italia Geniale. Design Enables. Having first premiered at the Pavilion Italia at Expo 2020 Dubai (1 October 2021 – 31 March 2022), the exhibition was dedicated to masterpieces of Italian industrial design and was curated by academicians from the Sapienza University of Rome and the Polytechnic University of Milan.

See the catalogue of the exhibition Italia Geniale. Design Enables here.

The exhibition was created in partnership with the Association for Industrial Design (ADI), the Union of Italian Chambers of Commerce, Industry, Handicraft and Agriculture (Unioncamere), and the Italian Trade Agency (ITA), and featured sixty world-famous products of Italian design, dating from the 1930s until today, supplemented with their original projects and patents. The exhibits – which included the Tolomeo lamp, designed in 1988 by Michele De Lucchi for Artemide, and the Valentine typewriter designed in 1970 by Ettore Sottsass for Olivetti, to mention only a few – were divided into five sections:

IMAGIN ABLE WORK ABLE RELATION ABLE LIVE ABLE MOVE ABLE

The RELATION ABLE section included sixteen iconic objects ranging from Poltrona Frau’s ‘Vanity Fair’ armchairs (1930) to the ‘Sacco’ (1970) by Piero Gatti, Cesare Paolini, and Franco Teodoro for Zanotta, as well as another small ‘relationable’ object of particular interest: the Campari Soda bottle, i.e. the iconic cone-shaped bottle of Campari Soda, a low-alcoholic mix of the celebrated bright-red coloured Campari and soda water.

The bottle was designed in 1932 by the Futurist artist, poet, and designer Fortunato Depero (1892-1960) for the Milanese Davide Campari (1867-1936), founder of the eponymous company. Campari was a great patron of the arts and one of the first Italian entrepreneurs to understand not only the crucial role of design and advertising, but also the importance of infusing creativity into industrial processes.

Davide Campari (left) and Fortunato Depero (right), portraits by unidentified artists.

The history of ‘The Bottle’, as it was renamed, is summarized in the exhibition catalogue:

In 1932 Davide Campari asked Fortunato Depero to design a new bottle for Campari Soda, a mix of Campari and soda water that was the first single-serving “ready-to-use” aperitif among those with a low alcohol content and a product destined to revolutionize habits. Depero’s design was inspired by a sketch from 1925, which represented a puppet about to drink from a cone-shaped glass. Starting from that suggestive image, the artist revolutionized the typical conical shape of an aperitif glass and thereby created a highly recognizable object which soon became a true manifesto of an era. […] The bottle represented the culmination of a partnership between Depero and Campari that began in the 1920s. At the same time, it was representative of both the Futurist vision and an intense relationship between art and industry, which emerged precisely in that period.

The inclusion of ‘The Bottle’ in this exhibition provides us an opportunity to briefly present here a book that celebrates this new form of patronage, the ‘numero unico’ or ‘unique issue’ Saggio futurista 1932, which will also be included in the forthcoming catalogue Italian Books 3.

This ‘unique issue’ was created by Depero on the occasion of a visit by the founder of the Futurist movement Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) to Rovereto, Depero’s hometown and the seat of the Casa d’Arte Futurista Depero (The House of Futurist Art Depero). Opened in 1919, the Casa had a highly innovative and multilayered organization, operating simultaneously as an art laboratory and a working advertising agency. In 1957 Depero decided to transform it into a museum – the only museum founded by a Futurist – to house and display his multifarious creations, from paintings and drawings to mosaics, patchwork tapestries, and even furniture.

After a lengthy restoration, The Casa d’Arte Depero is undeed now open to visitors, and belongs to the MART, or Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto (see more information here).

Saggio futurista 1932. Plate showing the tapestry ‘Mucca in montagna’, created by Depero in 1926.

The Saggio futurista 1932 gathers various texts and parolibere (or words-in-freedom), composed not only by Depero, but also by Marinetti and other Futurists, such as Giacomo Balla and Enrico Prampolini.

The publication also includes numerous colour and black-and-white illustrations, and represents one of the best examples of Depero’s revolutionary and highly influential graphic design, with its dynamic, bold, parolibere-inspired text, broken lines, and strong colouring.

Depero’s style is already visible on the striking salmon-pink wrappers. On the upper cover, the publication’s four-line title is written in black between five gilt lines, the first and last of which extend to form, respectively, the letters ‘F’ (referring to ‘Futurismo’ as well as to ‘Filippo’, i.e. Marinetti’s first name) and ‘T’ (referring to ‘Trentino’ as well as to ‘Tommaso’, i.e. Marinetti’s second name).

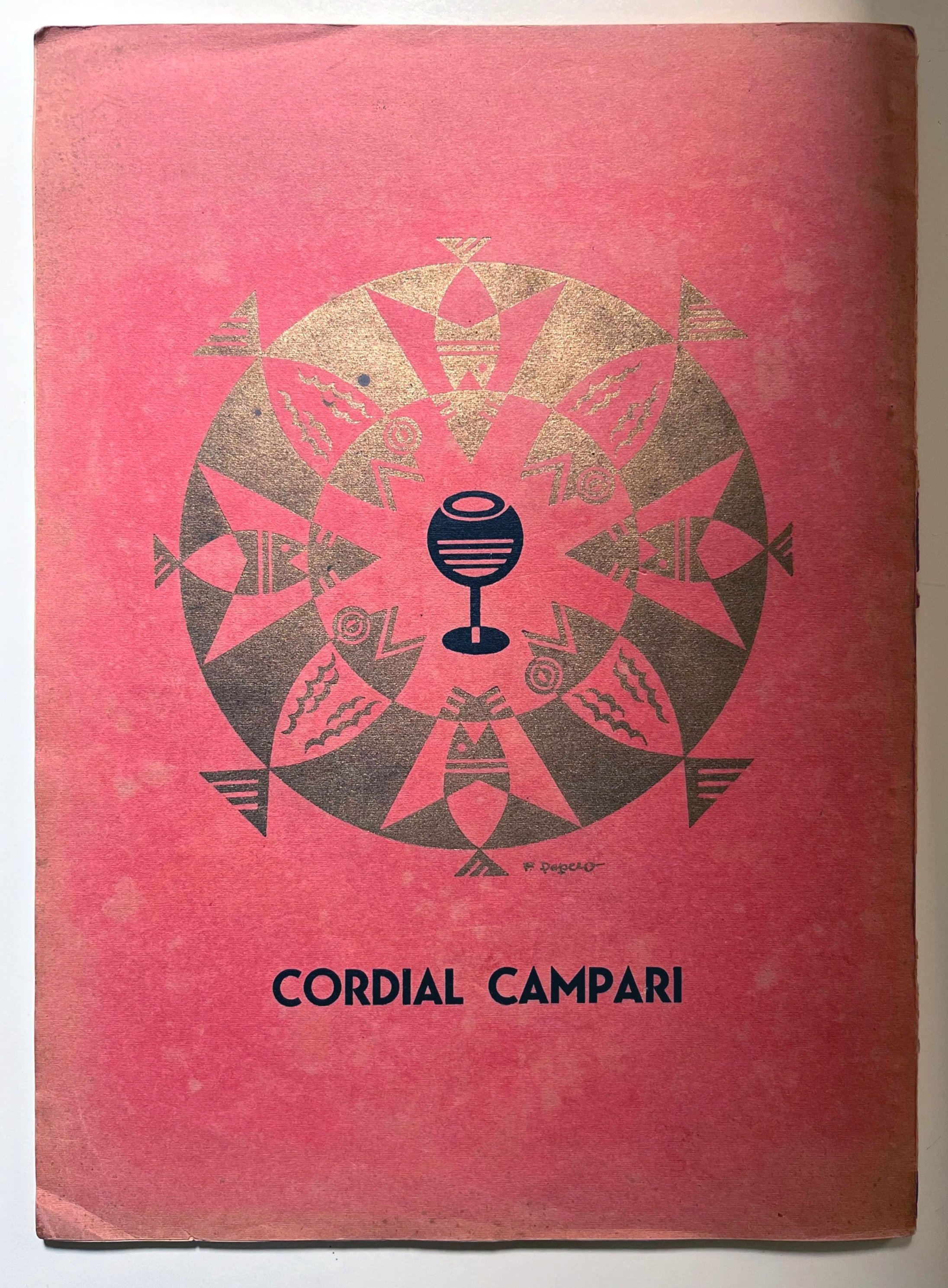

The lower cover is illustrated with an advertisement, printed in black and gilt, designed by Depero for Campari Cordial, the liquor created by Davide Campari in 1887 and produced until the 1990s. It was, indeed, that very Milan-based liquor company that was partially responsible for sponsoring the publication of the Saggio futurista 1932.

Depero officially began collaborating with Campari in 1927, after having painted, for the xv Venice Biennale of 1926, the advertisement Squisito al Selz, a famous example of Depero’s iconic style with that parolibere-inspired lettering, broken lines, and strong colouring. A reproduction of this ‘classic’ advertisement, mounted on cardboard, is included in the Saggio futurista 1932.

Other advertisements designed for the Milanese company, and especially for the Bitter and Cordial Campari, are also scattered throughout the publication, printed in black and white.

Meanwhile, the final pages of the Saggio Futurista 1932, which are printed on a different, yellow paper, present advertisements created by Depero for smaller companies and shops located in Rovereto.

In 1931, Davide Campari had also sponsored the publication of the Numero unico futurista Campari, which included Depero’s Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria, a revolutionary manifesto in which the artist broke down the divide between ‘high art’ and advertising and conceived of companies as heirs of the great patronage of the Renaissance.

The copy of the Saggio Futurista 1932 presented here is itself a testament to this new form of patronage, in that Depero gave it as a gift to another great patron of his multifaceted talent, the entrepreneur and art collector Arturo Benvenuto Ottolenghi (1887-1951).

The title-page bears Depero’s autograph address to his patron, ‘Sempre ed immutabilmente ad Arturo Benvenuto Ottolenghi Fortunato Depero Rovereto 18 aprile 1932’.

A dedication to Ottolenghi was also penned by Marinetti at the margins of the halftone photographic portrait of him included in the Saggio Futurista 1932, ‘a Arturo Benvenuto Ottolenghi con simpatia futurista F. T. Marinetti’.

Arturo Benedetto Ottolenghi and his wife Herta von Wedekind zu Horst (1885-1953) had transformed their residence at Acqui Terme, in Monferrato (Piedmont), into a center for artists. Depero himself was invited to work at the Villa, which had originally been designed by architect Federico d’Amato and the aforementioned Marcello Piacentini. The Villa and its gardens soon became a real museum of arts, thanks to works gifted by its artists in residence, which included Arturo Martini, Ferruccio Ferrazzi, and Adolfo Wildt, and of course Depero himself.

Ottolenghi was also the main sponsor of Depero’s first trip to New York in 1928. The journey, which was visually and textually documented in the Saggio futurista 1932, was made possible thanks to the ‘10.000 lire’ gifted by his generous patron, as Depero himself recounted in an undated letter to his friend Gianni Mattioli, stamped on 7 December 1928:

Three days before setting sail, I did not have enough money to pay in advance for my return ticket and could not get any reduction. I had despair in my soul – Rosetta [Depero’s wife] was crying tears like walnuts – I was mad and could not sleep. On the eve of my departure, when I was about to pay the total amount, a dear friend from Genoa, an industrialist, understood my state of mind and gave me 10,000 lire…

(quoted from R. Bedarida, “Bombs Against the Skyscrapers. Depero’s Strange Love Affair with New York 1928-1949”, Italian Modern Art, 1 (2019), p. 26; our transl.)

Depero’s grateful dedication to Ottolenghi on the title-page of the copy presented here underlines his continued gratitude: ‘sempre e immutabilmente’, ‘always and unalterably’.

How to cite this information

Margherita Palumbo, “The New Patronage,” PRPH Books, 16 March 2022, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/the-new-patronage. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.