On Girolamo Zanetti, Editor of the Oldest Chronicle of Venice

In 1765, the editio princeps of the oldest surviving Venetian chronicle appeared under the title Chronicon Venetum — presented here in a luxury copy, printed on thick blue paper — edited by antiquarian Girolamo Francesco Zanetti (1713-1781) on the basis of a manuscript then in the possession of his fellow Venetian Apostolo Zeno (1669-1750), whose textual version was collated with two codices preserved in the Vatican Library.

Written in the early eleventh century, the Chronicle of Venice covers the period from the sixth century to 1008, beginning with the Lombard invasion of Italy ca. 569 and ending with the rule of Pietro II Orseolo (991-1008). Very few contemporary documents survive from Venice’s early period, such that this work remains an extremely valuable source. There are in fact eight manuscripts of the chronicle, only three of which date to before 1500. The manuscripts do not share a common title and do not name the author. In fact, the chronicle was long thought to be the work of Giovanni Sagornino, as Zanetti attributes it here. This attribution persisted until the nineteenth century, when the attribution to Ioannes Diaconus (John the Deacon) gained general acceptance, owing to the prominence of the latter in the chronicle, along with certain detailed accounts of the period under the rule of Pietro II Orseolo, for whom John served as ambassador and chaplain.

Ioannes, Diaconus (ca. 965-1018). Chronicon Venetum omnium quae circumferuntur vetustissimum et Johanni Sagornino vulgo tributum e Mss. codice Apostoli Zeno V.Cl. nunc primum Cum Mss. Codicibus Vaticanis collatum, Notisque illustratum in lucem profert. H. Fr. Zanetti Al. F. Venice, 1765.

See the full description of this copy here.

This Venetian chronicle enjoyed lasting popularity; included among its legacy of readers was the especially noteworthy English critic and writer John Ruskin (1819-1900), who referenced the Chronicon Venetum (then still understood to be by Sagornino) in his celebrated work on Venetian art and architecture, The Stones of Venice, which first appeared in 1851. Since that time the text has been revised and the most recent translation is by Luigi Andrea Berto, who published it under the title Istoria Veneticorum in 1999. (1) Evidently, an air of mystery continues to follow the critical chronicle, which has been the subject of intensive work of late. (2) Something of the sort also befalls its first editor, Girolamo Zanetti, whose legacy recent work by scholar Maria Chiara Piva has done much to recover.

The witty and erudite Girolamo Zanetti was born in Venice, the youngest of Alessandro Zanetti and Antonia Limonti’s five children. Girolamo would later describe his father, a tradesman, as not very learned but a great lover of sciences and the fine arts, and he was evidently enthusiastic enough in these arenas, for at least two of the children succeeded in establishing themselves as important figures in the cultural milieu of eighteenth-century Venice. (3)

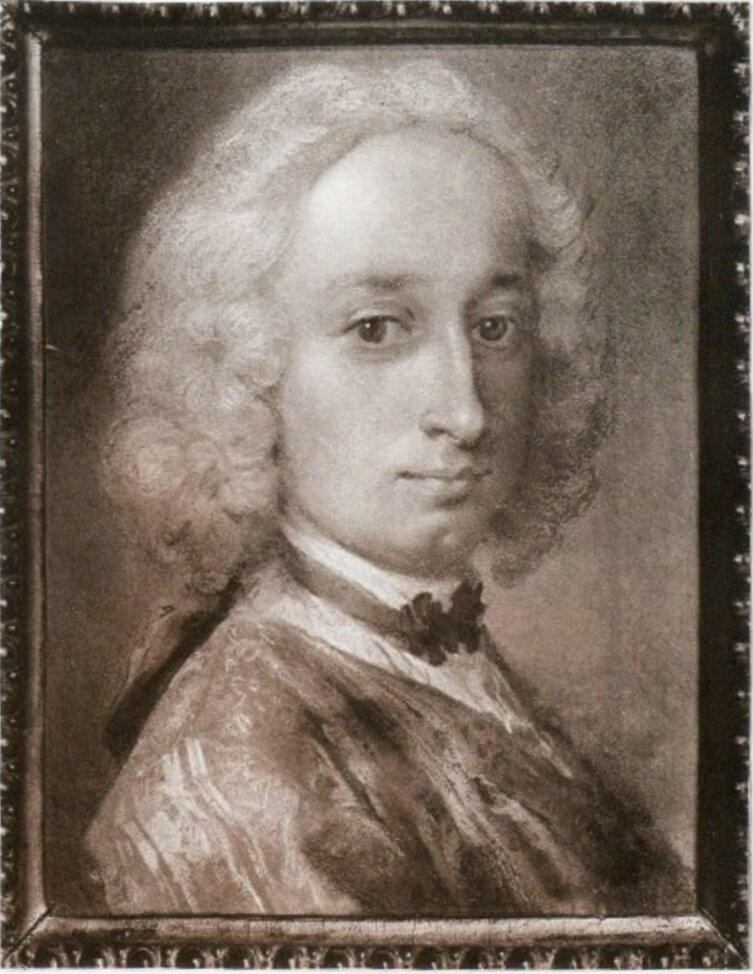

Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of Girolamo Zanetti, from Antonio Muñoz, Pièces de choix de la collection du Compte Grégoire Stroganoff, Rome 1912, v. II, p.49, pl. XXXIV.

It helped that Girolamo’s older cousin Anton Maria Zanetti the Elder (1680-1767) was already making a name for himself as a great artist, connoisseur, and collector of drawings and prints with various ties across Europe. Meanwhile, Girolamo’s older brother, Anton Maria Zanetti the Younger (1706-1778) was an accomplished artist and art historian, who later became librarian of the Marciana Library from 1738 until his death in 1778 (at which point the position went to Jacopo Morelli).

Giovanni Antonio Faldoni after Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of Anton Maria Zanetti the Elder, ca. 1725, Metropolitan Museum, New York, Public Domain.

Clearly, the Zanetti family tended to stick with a few select names, an issue which has continued to plague scholars dealing with their work. In his lifetime, Anton Maria Zanetti the Elder, the son of another Girolamo Zanetti, used “Anton Maria Zanetti di Girolamo” to differentiate himself from his younger cousin, though this inadvertently contributed to further confusion in later years, following our Girolamo’s own incursion into the literary world.

The older Anton Maria did of course come to prominence first. A talented artist, engraver, critic, and dealer, he amassed an important collection of drawings, prints, and gems, and his expertise were highly sought, especially by English travellers on the Grand Tour but also by collectors across Europe.

Much of Anton Maria the Younger’s early training in art and engraving came from making copies of works in the elder cousin’s collection, and the pair collaborated on projects. In the 1720s they began work on an illustrated catalogue of all the ancient sculptures in Venice’s public buildings. The catalogue was finally published in two volumes in 1740 and 1743 as Delle antiche statue greche e romane che nell’antisala della Libreria di San Marco e in altri luoghi pubblici di Venezia si trovano – albeit now limited to only 100 examples – and included Girolamo Zanetti’s Italian translation of Anton Francesco Gori’s Latin commentary. Subscribers to the work included Pierre-Jean Mariette, Pierre Crozat, and Apostolo Zeno, whose commentary was also initially to be included. It was, in fact, in Zeno’s library that the Venetian chronicle ultimately translated by Girolamo Zanetti was later discovered by Girolamo Tartarotti, to Zeno’s own surprise. (4)

Anton Maria Zanetti the Younger, Anton Maria Zanetti the Elder, and Girolamo Zanetti, Delle antiche statue Greche e Romane: che nell' antisala della libreria di San Marco, e in altri luoghi pubblici di Venezia si trovano, vol. II, Venice 1743.

It was during these years that Anton Maria Zanetti was commissioned by Lorenzo Tiepolo to catalogue first the statuary of the Marciana Library, of which Tiepolo was then the librarian, and then its manuscripts, a task he undertook with the help of Antonio Bongiovanni. The intimate knowledge Zanetti formed of the Library during these projects provided an excellent foundation for when he took over its charge in 1737. His commitment to Venetian art remained a strong current throughout his life, however, and he also became the first inspector of public paintings for the Serenissima.

Girolamo Zanetti’s strong interest in Venice’s cultural history was formed in this context. His early studies were under the Jesuits and he learned ancient languages, partly with the help of his brother Anton Maria. He went on to study law and even practiced as a lawyer for a period, but his antiquarian and philological interests soon won him over.

Girolamo’s great erudition ultimately allowed him to publish on a broad array of topics. Early on, he collaborated again with Anton Maria the Elder and Gori in translating Gori’s descriptions of the elder Zanetti’s collection of gems and cameos, which was published in 1750. Soon after that, he worked with Giovanni degli Agostini to edit the general catalogue of the Bibliotheca Smithiana, the library amassed by the famous British consul in Venice Joseph Smith, which was published by Pasquali in 1755.

Girolamo’s interest in collaboration is also evident in the series of topical periodical dissertations he published with Angelo Calogerà and Zaccaria Seriman under the title Memorie per servire alla storia letteraria e civile (1753–1759). Indeed, he was, like his friend Gasparo Gozzi, an important figure in the “new” kind of journalism taking shape in the period. In this series and other periodicals he published on a range of topics, sometimes polemical, from the latest discoveries pertaining to Venice’s oldest churches to recent literature, theatre, and other contemporary issues. He was also particularly interested – again like Gozzi and Bergalli, another dear friend – in French theatre, and translated Molière. He even wrote his librettos.

Despite the remarkable range of his work, Girolamo’s continued interest in ancient and medieval history remains apparent throughout his career, especially in terms of Venetian culture. It was, for instance, also in 1750 that he rose to prominence with a work on the history of Venetian currency, Dell'origine e della antichità della moneta viniziana ragionamento (Stamperia Albrizzi, Venice 1750). He went on to produce texts on the Etruscan language, Greek inscriptions, and ancient bas-reliefs, and in the 1760s he won prizes at the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres in Paris for a work on clothing worn by the Egyptians prior to the Ptolemies, and for a study on the difference between the Greek and Roman perspectives on Saturn and Rhea.

In 1758, Girolamo Zanetti’s Dell’origine di alcune arti principali appresso i Viniziani appeared, published in Venice by Stefano Orlandini. In it, the author located the Italian revival of the arts in Venice, in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. This was a strong claim in the years since Vasari’s Vite, with all the pride of place the latter put forth with its heavy emphasis on Florentine and Roman artists, to the well-justified chagrin of artists in Venice (and indeed everywhere else). Zanetti supported his thesis by recalling the foundational myth of Venice, in which Romans settled the islands and, from the fifth century, lived in relative geographical isolation and political autonomy from the rest of Europe, ultimately giving them an excellent position to be “among the first to restore the arts back to their former splendour and to raise them up from the thorns and muck where the Barbarians had left them bedraggled and crushed.” (5)

In her important study of Dell’origine di alcune arti principali appresso i Viniziani, Piva observes how Zanetti provided a rich and forward-looking analysis of medieval Venetian art by combining a reconsideration of “markedly ancient chronologies” with direct formal analysis of the works themselves. The result was a careful, thoughtful address of Venetian art and architecture that attempted to consider its value in terms of the works’ own contemporary contexts of production, a method not generally seen in art-historical studies of the time, and certainly not to this degree. (6)

Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of Anton Maria Zanetti, ca. on or before 1700. National Museum, Stockholm. Public domain.

Girolamo was clearly keenly aware of Venetian art of his own time as well. Especially noteworthy in this regard is his Elogio in celebration of the great Venetian artist Rosalba Carriera (1673-1757), which Zanetti read before the Academy of Fine Arts and Letters in Padua on December 6, 1781, the day before he died, and which was eventually published in 1818. (7) His family’s close ties to Carriera made him well-suited to compose this sympathetic work. In fact, Carriera’s earliest-known pastel portrait – dating to probably just before 1700 – is of Girolamo’s cousin, Anton Maria Zanetti the Elder, who stayed with Carriera in Paris in 1720-1721 and acted as her intermediary with the French collector Pierre Crozat. (8)

Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of Girolamo Zanetti, from Antonio Muñoz, Pièces de choix de la collection du Compte Grégoire Stroganoff, Rome 1912, v. II, p.49, pl. XXXIV.

The pastel portrait of Girolamo Zanetti pictured here, also attributed to Carriera, was listed in the Stroganoff collection, with the sitter identified by an inscription on the back of the frame. (9) In later years this portrait – the location of which is now unknown, after being sold at Sotheby’s in 1974 – has also been identified with Anton Maria the Elder, a misattribution, as Piva points out, that can only be explained by the heavy recurrence of select names in the Zanetti family. (10)

Indeed, Girolamo Zanetti’s own identity has been somewhat subordinated to the dense intellectual and artistic activity of which he was part. At the same time, the dense milieu of connections and enquiries also made him particularly well suited to undertaking the vast project represented by the Venetian chronicle, and though the provenance of this particular luxury, blue-paper copy of the Chronicon Venetum remains as yet obscure, it is intriguing to consider who may have been among its original owners, given the exciting cultural circles Zanetti and his family travelled.

1. Giovanni Diacono, Istoria Veneticorum, ed. Luigi Andrea Berto, Fonti per la Storia dell’Italia medievale. Storici italiani dal Cinquecento al Millecinquecento ad uso delle scuole 2, Bologna 1999.

2. See A. Pazienza, “Archival Documents as Narrative: The Sources of the Istoria Veneticorum and the Plea of Rižana,” in Venice and its neighbors from the 8th to 11th century: through renovation and continuity, eds. S. Gelichi and S. Gasparri, Boston 2018, and S. Marin, “Between Authorship and Anonymity: The Case of the Venetian Chronicles,” The Medieval Chronicle, 13 (2000).

3. Girolamo Zanetti, "Memoria," in Antonio Maria Zanetti the Younger, Varie pitture a fresco de’ principali maestri veneziani. Ora la prima volta con le stampe pubblicate, Venice 1760.

4. G. Sarton, “Girolamo Tartarotti, 1749,” Isis 39, no. 4 (November 1948), p. 207.

5. Cited in C. Piva, “Girolamo Francesco Zanetti and Dell’ origine di alcune arti principali appresso i Viniziani” in Re-Thinking, Re-Making, Re-Living Christian Origins, Viella 2018, p. 285.

6. Ibid, pp. 281-298.

7. G. Zanetti, Elogio di Rosalba Carriera, dalla tipograia di Alvisopoli, Venezia 1818, p. 9. On this work see C. Piva, “‘Breve ma veritiera Storia della vita di una nostra Pittrice’: l'elogio di Rosalba Carriera di Girolamo Zanetti,” in Storia della critica d'arte 3 (2019), pp. 189-217.

8. C. Piva, “‘Breve ma veritiera Storia della vita di una nostra Pittrice’: l'elogio di Rosalba Carriera di Girolamo Zanetti,” p. 190.

9. Antonio Muñoz, Pièces de choix de la collection du Compte Grégoire Stroganoff, Rome 1912, vol 2, p. 49, pl. XXXIV.

10. C. Piva, “‘Breve ma veritiera Storia della vita di una nostra Pittrice’: l'elogio di Rosalba Carriera di Girolamo Zanetti,” p. 196.

How to cite this information

Julia Stimac, “On Girolamo Zanetti, Editor of the Oldest Chronicle of Venice," PRPH Books, 30 June 2021, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/zanetti. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.