Twelve Blue Caesars and Numismatic Imagery in Venice

From the second installment of our Italian Books catalogue series – a special issue devoted entirely to printing on blue paper – we are highlighting an eighteenth-century book that is particularly remarkable for both its fine series of woodcuts and its distinguished provenance: Le vite de’ Dodici Cesari di Gajo Svetonio Tranquillo, the Italian translation of Suetonius’ De vitae XII. Caesarum, published in Venice in 1738.

De vitae XII. Caesarum (The Lives of the Twelve Caesars) was composed by the Roman historian, librarian and archivist Suetonius around 122 A.D., during the reign of the emperor Hadrian, and presents the biography of the ‘precursor’ to the first imperial dynasty, Julius Caesar, along with those of the first eleven emperors to follow him, from Augustus to Domitian. The work had a wide manuscript circulation, and from the Carolingian age onwards, it was one of the most popular classical texts, providing an exemplary model for the crafting of imperial biographies, or more generally for the genre of life writing of illustrious men. Suetonius’ biographies are richly detailed: the writer sketches individual portraits of each of the twelve Caesars, picturing their private lives, outlining their mental attitudes, enumerating their virtues and vices, and describing their physical characteristics. The work first appeared in print in Rome in August 1470, edited by Giovanni Antonio Campano, and issued by Giovanni Francesco da Lignamine. It was closely followed that same year by a second edition, published by the Roman press run by the German Conrad Sweynheym and Arnold Pannartz. Countless editions and translations into vernacular languages followed in the subsequent centuries.

Beyond the realm of biography and the cultural history of the Roman Empire, Suetonius’ Lives of the Twelve Caesars also had an enormous impact on the visual arts and on antiquarian imagery. For centuries, these lively descriptions represented a precious resource for paintings, prints, sculptures, and metalwork, thus reflecting the passion – even obsession – among rulers and princes for such imperial themes, while simultaneously giving new life to Suetonius’ Twelve Caesars. A couple examples, drawn from the numerous artworks that visualized Suetonius’ work, will suffice to show the extent of this cultural lineage: the eleven canvases of Roman emperors Titian produced in 1540 for the Camerino dei Cesari (Cabinet of the Caesars) of Federico Gonzaga Duke of Mantua, all of which were sadly lost in a fire in Spain in 1734; and the Renaissance silversmith masterpiece that is the Tazze Aldobrandini (1587/99), a set of twelve silver-gilt standing cups, each of which stands over a foot high and bears a statuette of one of the first twelve Caesars with episodes of their respective lives rendered in the shallow dish upon which they stand. The set was once in the possession of a member of the powerful Aldobrandini family, but is currently scattered across various collections worldwide.

Suetonius’ Lives also played a remarkable role in numismatic studies and coin collecting. Coins depicting the Twelve Caesars became a must-have for all refined collections, and as of the mid-sixteenth century, the emperors’ portraits in illustrated editions of Suetonius were usually based on antique coins. An example of this is the second, enlarged edition of the commentary on Suetonius published by Laevinus Torrentius, which first appeared in 1578 in Antwerp, and again in 1592, bearing a border-framed title-page with the medallion portraits of the Twelve Caesars surrounded by inscriptions imitating Roman coins. The 1675 Basel edition of Suetonius – which likewise enjoyed great popularity and was frequently reprinted – was edited by the well-known antiquarian Charles Patin and also fully illustrated with antique coins.

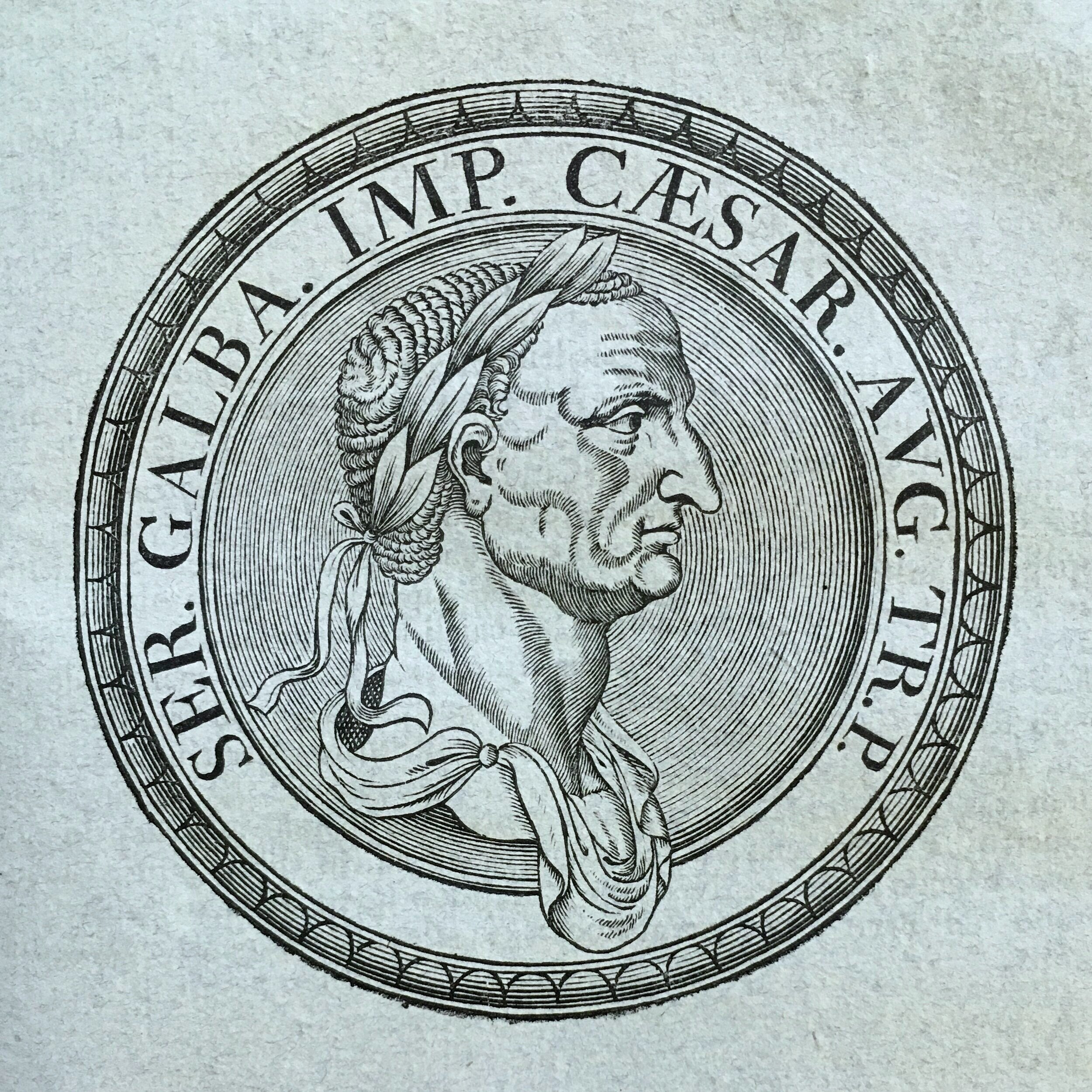

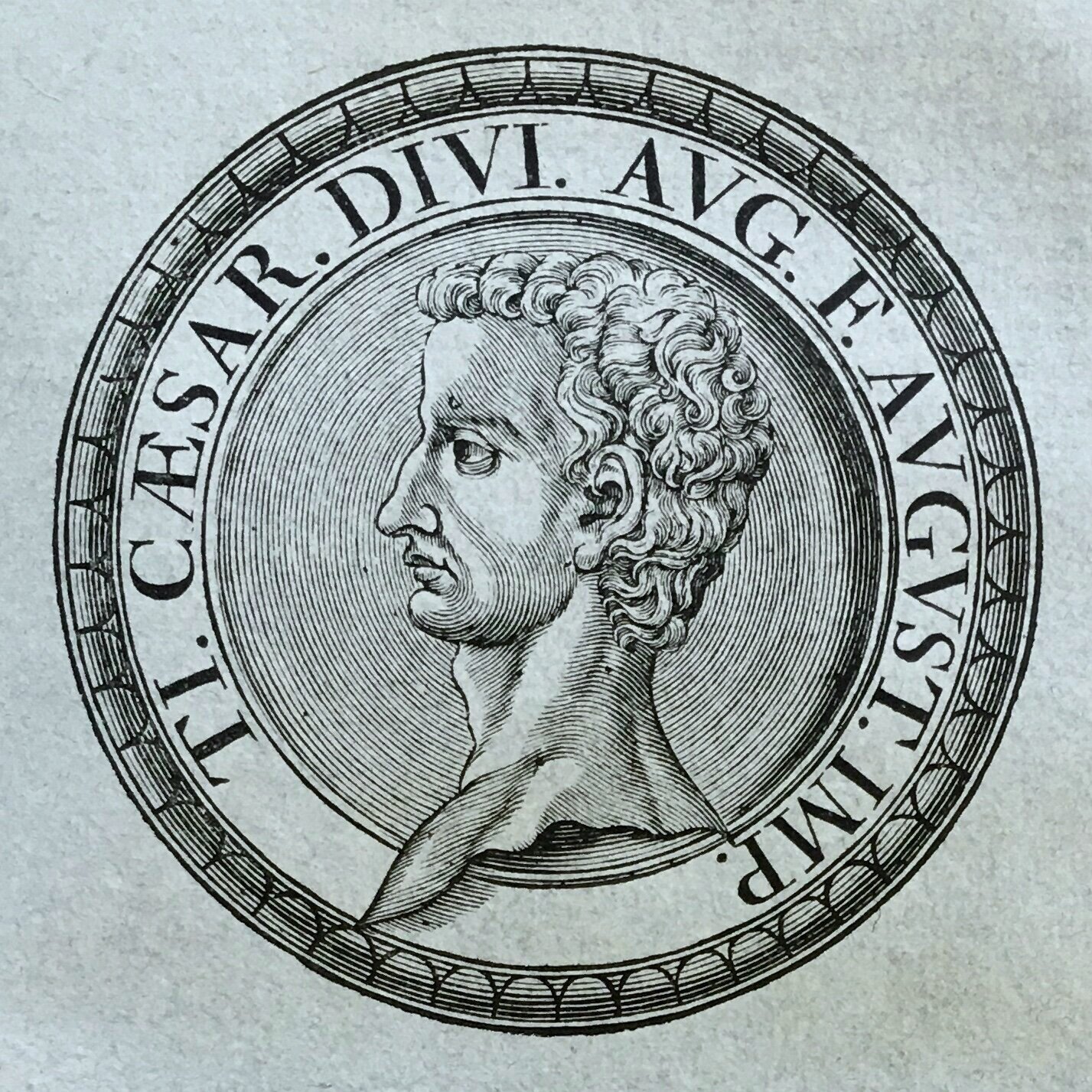

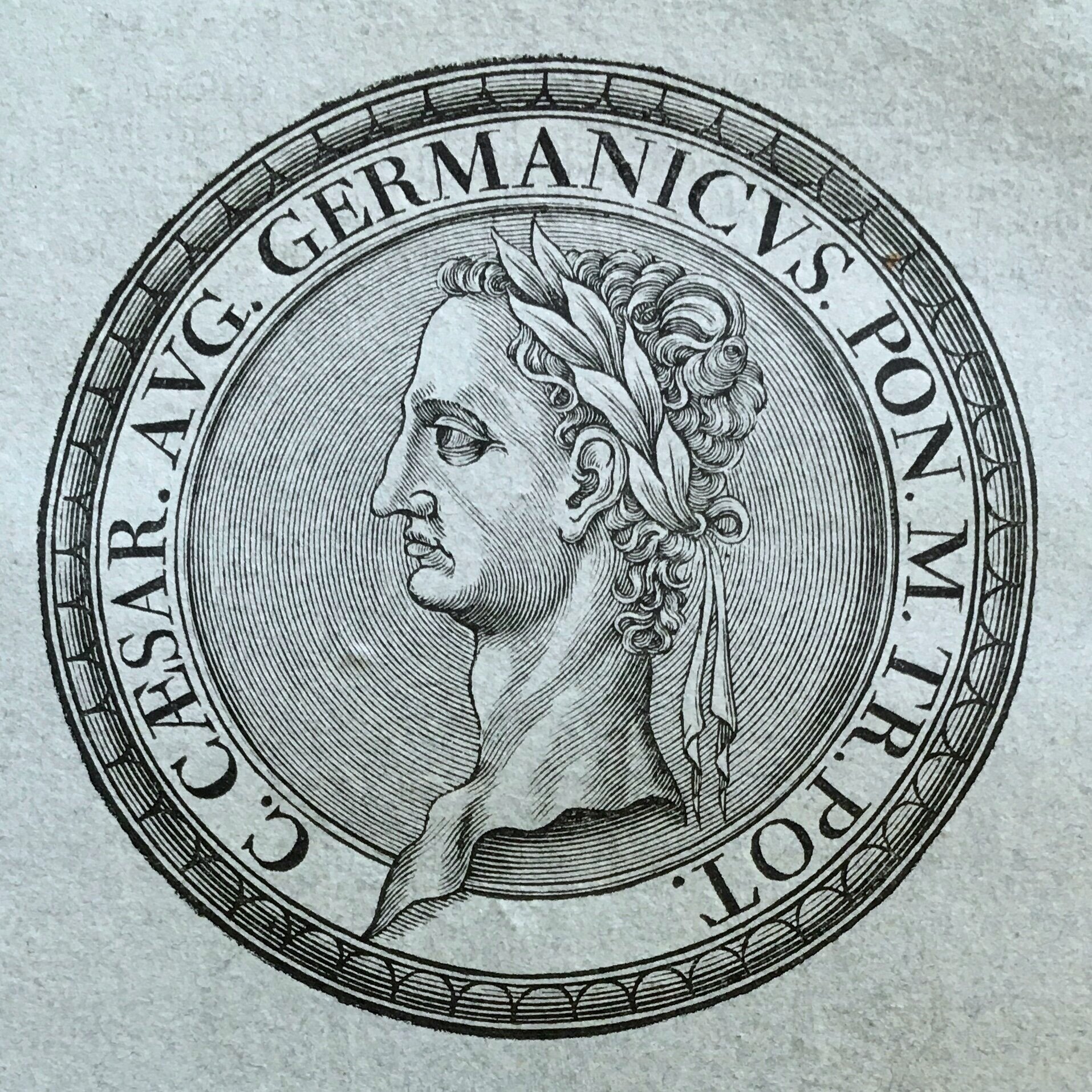

This close relationship between Suetonius’ Lives and numismatic imagery is clearly evident in the late Venetian edition of 1738, presented here in a rare copy printed on blue paper: Le vite de’ Dodici Cesari di Gajo Svetonio Tranquillo, published by Francesco Piacentini (see a complete description of this copy here). As the fine title-page printed in red and black ink states, the translation is that into ‘volgar Fiorentino’, i.e. in Florentine vernacular made by Paolo Del Rosso (1505-1569), issued in Rome in 1544 by Antonio Blado, at the expense of Francesco Priscianese. In his preliminary address to the reader, the printer Piacentini briefly presents the highly esteemed translation by Del Rosso, which is introduced – as in the original edition of 1544 – by the dedicatory epistle to the Florentine ambassador at the court of Pope Paul III, signed by Francesco Priscianese. He goes on to enumerate the novelties and improvements of his new edition, citing above all its illustrative apparatus, which includes – as announced on the title-page – ‘le vere effigie de’ Cesari’, the true, reliable portraits of the Caesars. i.e. the woodcut medallions portraying each of the Twelve Caesars, as a visual introduction to the biographies.

As the printer explains, these images closely reproduce the outline of the series of medallions originally executed by the outstanding Flemish painter, numismatic, and antiquarian Hubert Goltzius (1526-1583), which first appeared in his Vivae omnium Imperatorum Imagines, published in Antwerp in 1557 by Gilles Coppens van Diest.

Anthonis Moor. Portrait of Hubert Goltzius, 1573-74. Bruxelles, Musées Royaux des Beaux Arts de Belgique (public domain).

Piacentini emphasizes the accuracy of the intaglio woodcut images included – on the example of Goltzius’s Vivae omnium Imperatorum Imagines – in the publication, as well as the great financial cost necessary for their realization: producing copper engravings would have been much cheaper. However, the Venetian printer did not follow Goltzius’ example entirely. The Flemish artist had, in fact, rendered his woodcut portraits in chiaroscuro, using a printing technique that flourished especially in sixteenth-century Italy, as the companion catalogue of the 2018 exhibition The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy, curated by Naoko Takahatake at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, strikingly attests.

The chiaroscuro woodcut – whose invention is attributed by Giorgio Vasari to Ugo da Carpi (1480-1532) – is a rather elaborate technique, that “involves the superimposed printing of multiple blocks of different colors, with the ostensible aim of imitating the effects of certain kinds of drawings […] In a two-block chiaroscuro woodcut, the line block is commonly inked in black or dark grey, while the tone block color can vary greatly […] When two or more tome blocks are used, they are typically printed in a graduated shades of the same hue to render tonal values” (The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy, p. 12). The paper provides the white highlights (see an example of chiaroscuro effects rendered by hand, also on blue paper, here).

The result is magnificent. “In its size and scale Vivae omnium Imperatorum Imagines is without precedent in the field of numismatics. Although other publishers and printmakers issued volumes containing illustrations of antique medallions, their undertakings were more modest than Hubert Goltzius’ large folios, with their full-page chiaroscuros. Comparing these earlier numismatic texts (or even Hubert Goltzius’s own later volumes) to the Imagines shows how effective the addition of color was. The chiaroscuro prints are far more successful than black and white woodcuts or engravings in capturing the metallic and sculptural qualities of the coins” (N. Bialler, Chiaroscuro Woodcuts. Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617) and his Time, Amsterdam 1992, pp. 31-32).

This chiaroscuro technique was possibly too elaborate for Francesco Piacentini, who rendered the portraits of the Twelve Caesars with a single tone block. Moreover, when the complete works of Goltzius – including the Vivae omnium Imperatorum Imagines – were reprinted in 1644-45 by the Officina Plantiniana, the series of portraits of emperors and empresses were printed as traditional woodcuts.

Regardless of the technique used, the 1738 Suetonius is rightly considered one of the finest examples of Venetian illustration. The woodcuts are perfectly outlined, and the effect in re-creating antique coins is even finer in the case of the copy presented here, in which the well-inked medallions clearly stand out against the blue-paper ground.

The fine illustrative apparatus is further enriched by an elaborate woodcut border framing the half-title, signed by the English artist John Baptist Jackson (1701-1780), which offers a compendium of motives from Antiquity: vases, columns, arms, shields, armors, hermae, and of course coins.

At the top, the motto ‘ex intimo sui surgit’, used by Piacentini in his device, which is printed on the red and black title-page.

Jackson was born in Battersea in 1701. After having learned the rudiments of printmaking in England, he moved to Paris in 1725, where he studied the technique of chiaroscuro woodcuts with Jean Michel Papillon and Vincent le Sueur. Later, in 1731, he travelled to Venice, where he resided until 1745. His Venetian stay was decisive for his career as an engraver and illustrator: eighteenth-century Venice was an important centre for the printmaking revival and the production of finely illustrated books. There, Jackson could also find generous support from another English resident, the great collector and art dealer Joseph Smith (1682-1770), who had settled in Venice in the 1700s and in 1744 would be named British Consul of the city. Smith – or, to borrow Horace Walpole’s words, the ‘The Merchant of Venice’, – also had close relationships to printers and publishers; as of the 1730s he had an active role – not only as a financial backer – in the press directed by Giovanni Battista Pasquali (1702-1784), which produced some of the finest books in Venice.

Further, Smith had an authentic passion for drawings and prints, which quickly made him a veritable ‘impresario of printmaking’. His name is closely linked to one of the most important Venetian artists of the age, Antonio Canal, better known as Canaletto (1697-1768). As a mark of gratitude towards his munificent patron, Canaletto dedicated his celebrated set of etched views Vedute Altre prese da i Luoghi altre ideate da Antonio Canal e da esso intagliate poste in prospetiva (1744) – one of the most impressive eighteenth-century series of views of Venice and surrounding areas ever made – to ‘Ill.mo Giuseppe Smith Console di S. M. Britannica’.

From Canaletto’s Vedute Altre prese da i Luoghi altre ideate da Antonio Canal.

Smith introduced Jackson to his wide artistic and publishing network in Venice, and commissioned him to make chiaroscuro woodcuts from two artworks preserved in his palace overlooking the Canal Grande, a bronze sculpture by Giambologna, and Rembrandt’s painting Descent from the Cross (now in the National Gallery of London). He also encouraged Jackson to undertake a more ambitious project, i.e. to reproduce, in chiaroscuro, works by Venetian masters such as Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto, and Jacopo Bassano, which were located in various churches and confraternities, or scole. From 1739 onwards, Jackson dedicated himself to this project, and realized a series of seventeen chiaroscuro woodcuts, which the British Consul collected into a volume published by Giambattista Pasquali in 1745 (Titiani Vecelii, Pauli Caliari, Jacobi Robusti, et Jacopi de Ponte opera selectiora a Joanne Baptista Jackson Anglo ligno coelata et coloribus adumbrata).

Although in 1738 Jackson had only signed the fine woodcut border framing the half-title of the 1738 Suetonius, and the medallion portraits of the twelve Roman emperors are generally attributed to anonymous designers and engravers, some scholars suggest that Jackson himself may have collaborated on the realization of these traditional woodcuts.

Owing to his sour temperament, and rivalry with other printmakers active in the lagoon, Jackson was however not entirely able to profit from his Venetian relationships. In 1745 he returned to England, where he tried to apply his skills in chiaroscuro woodcutting technique to a commercial venture, establishing, a few years later, a wallpaper manufactory in Battersea. The initiative was a failure: he remembered – perhaps with regret – Venice and Smith’s patronage in a booklet he published in London in 1754, for promoting, albeit in vain, his manufactory, the Essay on the Invention of Engraving and Printing in Chiaro Oscuro, as practised by Albert Dürer, Hugo di Carpi, &c.

Many of the copies included in the special issue of our Italian Books catalogue devoted to works printed on blue paper bear distinguished provenances, pointing to some of the greatest names in this special sector of book collecting. The fine Le vite de’ dodici Cesari of 1738 is no exception. The earliest known owner was in fact the Venetian patrician and senator of the Serenissima Giacomo Soranzo (1686-1761), as attested by his ownership inscription on the recto of the front flyleaf, ‘1743 Di Giano Soranzo’.

Soranzo was one of the greatest collectors of works printed on blue paper. His magnificent library – comprising 4,000 manuscripts and about 20,000 printed books – was mostly sold by his heirs between 1780 and 1781. Volumes bearing his ownership mark are scattered worldwide; however, this special copy of the Suetonius on blue paper had already changed owners during Soranzo’s life, passing precisely into the hands of one of the great protagonists of our post: the British Consul Smith. Smith’s large ex libris – finely engraved by another great Venetian artist who enjoyed Smith’s munificent patronage, Antonio Visentini (1688-1782) – is pasted on the front pastedown. Vicentini is well known for the series of etchings entitled Prospectus Magni Canalis Venetiarum, all taken from Canaletto’s paintings, and issued by the Smith-Pasquali press in 1735.

In 1755, the general catalogue of the Bibliotheca Smithiana appeared, edited by Girolamo Francesco Zanetti and Giovanni degli Agostini, and printed by the ever loyal Pasquali, and characterized by the usual elegance and accuracy. Fifteen different editions of Suetonius’s Twelve Caesars are listed, starting from the Venetian Vitae that appeared in Venice in 1471, and including this very copy of the 1738 Suetonius, printed on thick blue paper:

“[Svetonius] la stessa, tradotta dal suddetto [Paolo Del Rosso], con le vere Effigie de’ Cesari (cavate da Goltzio) ed altre illustrazioni. Ven. per Francesco Piasentini [sic] 1738. 4. c. gr. turchina. leg. Oll.” (Bibliotheca Smithiana seu Catalogus librorum D. Josephi Smithii Angli, p. ccclviii).

Many of the Suetonius editions that belonged to the British Consul are illustrated. He also owned the aforementioned complete works of Goltzius published by the Officina Plantiniana, including the Vivae omnium Imperatorum Imagines. He did, after all, have a great interest in numismatics, and fittingly amassed an exquisite collection of antique coins and gems.

The 1755 catalogue represents the peak of Smith’s book collecting. Compelled by increasing financial difficulties, Smith resigned himself, in subsequent years, to selling his large library; his celebrated art collection, meanwhile, was mostly purchased by King George III in 1761, for the sum of 20,000 pounds. The British Museum preserves, almost intact, his precious collections of drawings and prints, which includes not only the great names of Canaletto and Visentini, but also chiaroscuro woodcuts by his dear Jackson. Among them, a three-quarter portrait in black, brown and ochre of Julius Caesar with a laurel wreath (see https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1918-0713-31), from an etching by Aegidius Sadeler II for his series The Emperors and Empresses of Rome (1597-1627), the drawing of which is attributed to Titian. In its wonderfully sinuous lines and variegated depths, it seems impossible that Jackson did not have in mind the fine models of the striking blue Venetian Suetonius presented here, and, more broadly, the ongoing importance of the imperial themes Suetonius put into circulation.

How to cite this information

Margherita Palumbo, “Twelve Blue Caesars and Numismatic Imagery in Venice,” PRPH Books, 21 October 2020, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/suetonius. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.