On This Day: Consecrations of The Old and New Basilicas of Saint Peter

Photo of Saint Peter’s Basilica and Piazza taken by Margherita Palumbo from the gardens of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (Vatican City). 5 November 2020.

On 18 November 323 AD, the first Basilica Sancti Petri, Saint Peter’s Basilica, was consecrated by Emperor Constantine over the tomb of Peter the Apostle, the first Roman Pontiff as well as the first patriarch of Antioch in the Eastern Christian tradition. The site was the former location of the ancient Circus of Emperor Nero, during whose reign Peter was martyred. Precisely 1300 years later, in 1626, the new Saint Peter’s was established on this day as well, after more than a century of construction. Its splendor and enormity have made it a singular monument. Saint Peter’s is arguably the most famous church of Christendom as well as the largest church in the world, and its story is a testament to the great spirit of creativity and ambition that fueled the High Renaissance and Baroque.

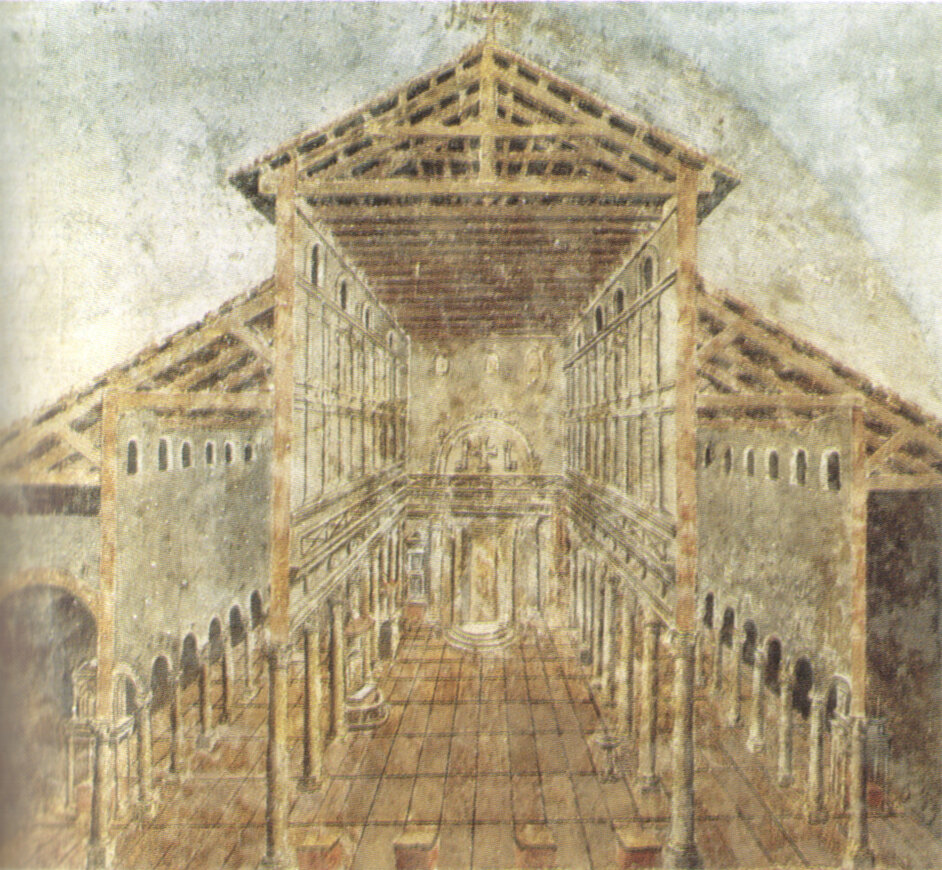

Fresco showing a cutaway interior view of the Old Saint Peter's Basilica as it looked in the fourth century. Public domain.

Pope Sylvester I (285-335) consecrated the first Saint Peter’s in the fourth century, following the building’s construction which lasted about 40 years. In the more than 1000 years that followed, the site became an especially important one for pilgrims and also held Papal coronations, as well as the coronation of Charlemagne in 800 as Holy Roman Emperor. In 846 the Basilica was sacked by raiders who also destroyed Saint Peter’s tomb, prompting Pope Leo IV to build the Leonine wall to protect the Basilica from future threats.

A conjectural view of the Old Saint Peter’s Basilica ca. 1483-1506 by H. W. Brewer, 1891. Public domain.

Over the years, however, especially through the displacement of the pope’s residence during the Avignon Papacy, the first basilica fell into ruin. Efforts to repair it were initiated by Pope Nicholas V (1397–1455), but it was Pope Julius II (1443-1513) who ultimately ordered the ancient building to be torn down due to structural concerns, and it is also he who organized a competition to find an architect capable of conjuring what was to be its new iteration (many of the designs of this competition are still preserved at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence).

Raphael, Portrait of Pope Julius II, 1511–12. Oil on wood. National Gallery, London. Public domain.

Julius II was an extraordinarily ambitious pope and a great patron of the arts. It is he, for instance, who commissioned Raphael to paint frescos in the suite of reception rooms at the Apostolic Palace now known as the “Raphael Rooms,” and he was also responsible for commissioning Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Furthermore, Julius II had commissioned Michelangelo to design his, the pope’s, own tomb, which was to be placed inside the new basilica. Indeed, this new basilica was to form no exception to the pope’s legacy of great patronage—rather, it was to represent the very epitome of High Renaissance architecture.

A design by Donato Bramante (1444-1514) won the competition organized by Julius II. This design exemplified the harmonious union of science and beauty that characterized the High Renaissance, with a perfectly geometrical arrangement of circles and squares within the centralized plan of a Greek cross. In reality, however, the edifice would ultimately end up being in the shape of a cruciform, the result of an amalgamation of visions, politics, and the general forces of time.

Bramante’s plan for the new Saint Peter's Basilica, 1506.

Indeed, work on the new basilica progressed slowly, and with many changing hands. Upon Bramante’s death, Raphael took over as lead architect, but he died on 1520 at the young age of 37. In 1547, after various more shifts in organization, an elderly Michelangelo was named ‘Capomaestro’, that is, superintendent in charge of the building project, and it is he who is responsible for how much of the building finally looks today.

Still, it was still not until 1590 that the famous dome was completed, 26 years after Michelangelo’s death. The dome—which Michelangelo had begun conceiving in relation to Brunelleschi’s famous dome in Florence—is evident in the famous summa of Roman topography and statuary, the Romanae Urbis Topographiae & Antiquitatum… by the French antiquarian and poet Jean-Jacques Boissard (1528-1602).

Boissard, Jean-Jacques (1528-1602). Romanae Urbis Topographiae & Antiquitatum… Frankfurt, Johann Feyrabend for Theodor de Bry, 1597-1602.

See the full description here.

PrPh is pleased to be currently offering a copy of Boissard’s great work bearing a distinguished provenance and pictured here. The work was published in Frankfurt by Johann Feyrabend for Theodor de Bry between 1597 and 1602. It is profusely illustrated, De Bry himself having been responsible for many of the fine engravings included, and in the copy currently on offer, the engravings are presented in their first state.

The Antiquitates were intended to offer scholars and visitors to Rome a travel guide of the city while also offering precious testimony to its Renaissance glory through information on its great archeological collections and a clear display of the antiquarian taste of that time.

Of the greatest importance is, in Part II, the map of modern Rome, 'NOVISSIMA VRBIS ROMAE DESCRIPTIO A° M.D.LXXXXVII.', engraved by de Bry and depicting the façade of Saint Peter’s Basilica as it had developed to that point, before the Ticino-born architect Carlo Maderno (1556-1629) extended upon Michelangelo’s plan, designed the basilica’s nave and created its grand Baroque façade. Here the basilica is intentionally oriented toward the reader and not toward the Obelisk and the Vatican Gardens, as it is in reality (see Frutaz, CXXXVIII, pl. 278).

The Vatican Gardens, meanwhile, can be seen in Giovann Batista Falda’s marvelous survey of Baroque gardens, I Giardini di Roma, published in Rome by Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi, ca. 1680, a wonderful copy of which we are pleased to currently offer as well.

Falda, Giovan Battista (1643-1678). I Giardini di Roma. Con le loro Piante Alzate e Vedute in Prospettiva.... Roma, Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi, [ca. 1680].

See the full description here.

Among gardens by many other distinguished figures, Falda also includes those by Maderno and by Maderno’s uncle, the architect Domenico Fontana (1543-1607), who (among many other things), in 1586 was responsible for moving the large Egyptian obelisk from beside Saint Peter’s to its current place in the centre of the piazza.

The obelisk placement is significant because of Saint Peter’s history: the apostle’s crucifixion took place close to the obelisk in the Circus of Nero, and its later position in Saint Peter’s Square acts as a witness to his death.

Falda has one more particularly interesting connection to the new Saint Peter’s Basilica: as a boy, he was sent to Rome to work in the studio of Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), the famous sculptor and architect who would help define the Baroque style and who was a critical figure in the prolonged design and construction history of the basilica: he would add no less than the Cathedra Petri, the Baldacchino, and the celebrated piazza, Saint Peter’s Square.

While the magnificence of Saint Peter’s Basilica is without comparison, the grandeur and significance of the marvelous piazza is not to be underestimated. Its footprint is evident in the encyclopedic panorama of Rome produced by Giuseppe Vasi (1710-1782), the Prospetto dell 'Alma Cittá di Roma visto dal Monte Gianicolo of 1765.

Vasi, Giuseppe (1710-1782). Prospetto dell 'Alma Cittá di Roma visto dal Monte Gianicolo, 1765.

Complete suite of twelve joined etchings on wove paper, total platemark approx. 1015 x 2625 mm. (40 x 103 1/4 in), good margins, carefully dissected and mounted on linen, framed and under glass.

Composed of twelve joined etchings, the map lists and presents 390 monuments and sites, the numbering of which correspond to those in the guidebook that Vasi published in the same year. Seen from Monte Gianicolo and looking northeast, it shows Saint Peter's Basilica in the north (left), and the Fonte dell'acqua Paola in the east (right).

Detail showing the new Saint Peter’s Basilica with the Piazza created by Bernini, from Giuseppe Vasi (1710-1782), Prospetto dell 'Alma Cittá di Roma visto dal Monte Gianicolo, 1765.

As Vasi’s monumental panorama makes clear, the piazza forms as much of a contribution to the topography of the Roman landscape as the basilica’s dome does for its skyline. Its symbolic value is equally potent. As Bernini himself explained, his vast encircling of colonnades act like "the maternal arms of Mother Church," reaching out and embracing the faithful and reuniting the heretics.

Photo of Saint Peter’s Basilica and Piazza taken by Margherita Palumbo from the gardens of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (Vatican City). 5 November 2020.

Today, Saint Peter’s Basilica continues to inspire awe and fascination for worshippers and non-worshippers alike. As a monument to faith, art, science, and cultural heritage, it has also become a symbol of endurance and longevity, as this photograph by Margherita Palumbo taken on the eve of the recent lockdown measures due to the Covid-19 pandemic well attests. Seen from the gardens of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (Vatican City), the image captures the fortitude and magnificence of the Basilica in a moment of conspicuous quietness—a fine representation of the strength and grace of a nation that will undoubtedly persist despite the prolongation of these challenging times.

How to cite this information

Julia Stimac, “On This Day: Consecrations of The Old and New Basilicas of Saint Peter,” PRPH Books, 18 November 2020, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/stpetersbasilica. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

![Falda, Giovan Battista (1643-1678). I Giardini di Roma. Con le loro Piante Alzate e Vedute in Prospettiva.... Roma, Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi, [ca. 1680]. See the full description here.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1605721158331-JIHXSNU9AK45JJIXJ341/falda%2B2.jpg)