One of the Greatest Female Poets of the Renaissance: Gaspara Stampa and Her Rime

Gaspara Stampa’s Rime – presented here in its very rare first edition – represents an equally rare example of a ‘canzoniere’, or collection of love lyrics, written from the perspective of a woman to seduce a man. As the poet and virtuosa’s crowning achievement, it also represents one of the most important collections of lyric poems to come out of the Renaissance.

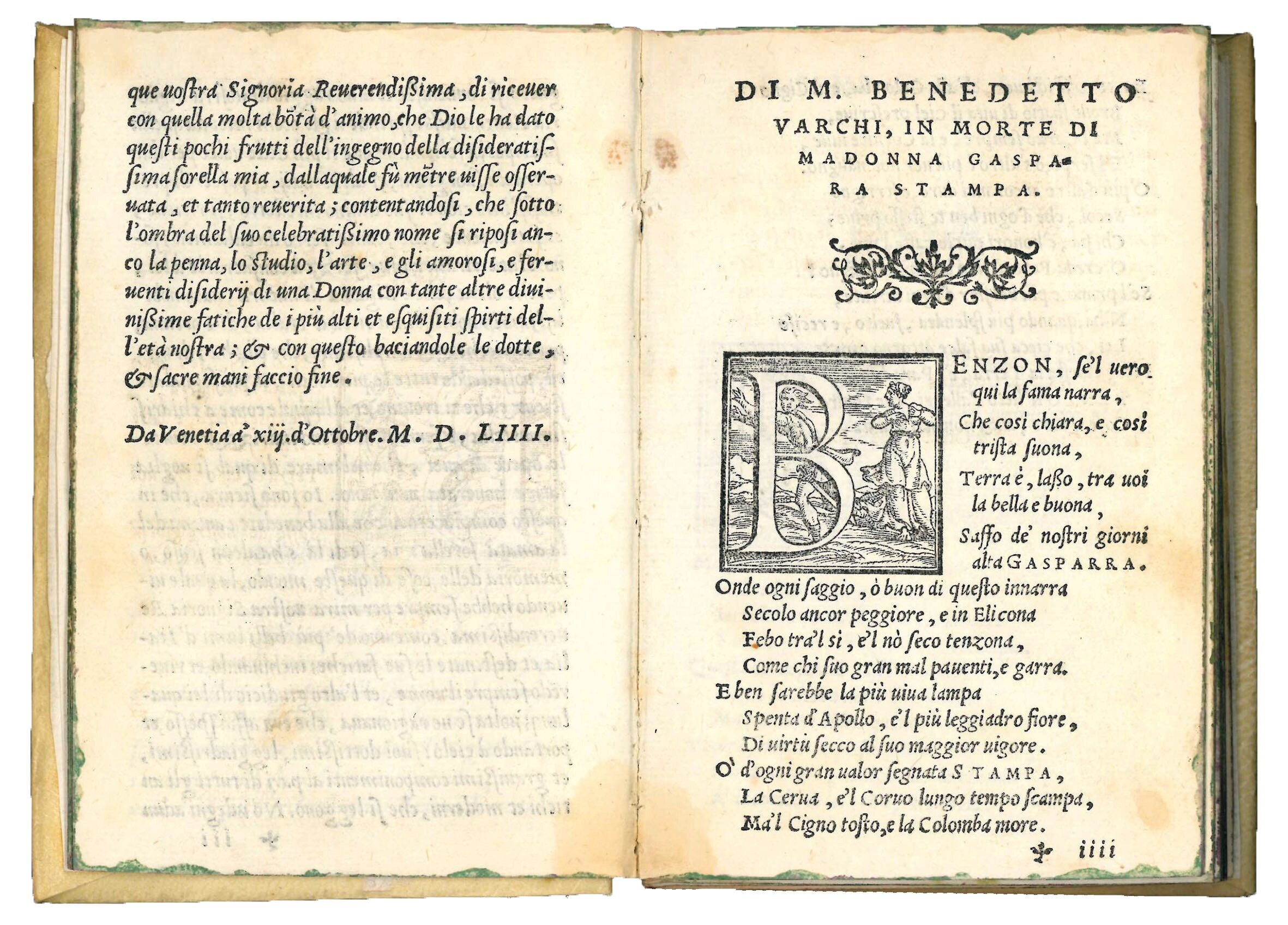

Gaspara Stampa (?1523 – 1554). Rime. Plinio Pietrasanta, Venice, 1554.

See more information about this copy here.

The work was published in Venice by Plinio Pietrasanta in 1554, a year after Stampa’s death in April 1553. At that time, her sister Cassandra had collected “quelle che si sono potute trovare” (‘all those [poems] that could be found’) and published them along with epistles and elegies by her and others. Giorgio Benzone, a family friend and a poet in his own right, assisted Cassandra with editing the project, which the latter dedicated, on October 13, 1554, to Giovanni Della Casa (1503-1556), archbishop of Benevento, papal ‘nuncio' to Venice, poet, etiquette and society writer, diplomat, and inquisitor, who was especially celebrated for his treatise on polite behavior, Il Galateo overo de’ costumi (1558). With this dedication, Cassandra writes, she will surely respect the will of the “benedetta anima della amata sorella mia […] la quale vivendo ebbe sempre per mira vostra Signoria Reverendissima, come uno de’ più belli lumi d’Italia” (‘blessed soul of my beloved sister […] who while living always had your Reverend Lordship in her sights as one of the most beautiful lights of Italy’, leaf Ψ2r).

Gaspara Stampa herself was, like Vittoria Colonna and Louise Labé (ca. 1524-1566), a leading luminary of Renaissance poetry, though, like theirs, her legacy has been dampened and distorted through centuries of gender biases. Stampa scholar Unn Falkeid explains the trajectory of her reception, noting that, “[d]espite Stampa’s impact on sixteenth-century Italian culture, during the two centuries following her death she was virtually forgotten until the 1738 republication of her poetry, and even then the strange editorial and reception history of her poetic corpus distorted her memory in such a way that her poetry never regained the prominence it once had.” (U. Falkeid & A.A. Feng, “Introduction”, in Rethinking Gaspara Stampa in the Canon of Renaissance Poetry, Farnham, 2015, p. 2) A primary issue was the fact that, like the majority of female cultural figures whose work has been subject to re-evaluation in the past few decades, “her biography, and especially, her presumed love affairs have tended to overshadow her works. In the last few decades, however, there has been a substantial increase in critical attention paid to Stampa’s poetry among both European and North American scholars who have sought to refocus Stampa scholarship on her poetics rather than the mystic love and its reception”. (p. 2)

Beyond making the sheer force, intensity, and innovation of her verses known to a wider audience, this re-appraisal has helped illuminate Stampa’s significance as a female writer. For not only was she obviously working in a male-dominated world, but her work also responds to, and develops upon the canzoniere model developed by Petrarch in the fourteenth century – a celebrated model in Stampa’s time but one based firmly on a male perspective, predicated on a male poet’s idealization of his female love. “Stampa is not only a woman following a literary code created by and for men, she writes her poetry with confidence, takes tone and makes woman’s voice heard where it traditionally does not exist. She makes a man a subject of her poems, hence he becomes both a muse and an object deprived of voice. She echoes, or even rewrites, Petrarchan poems, and she compares herself to both him and other legendary poets. Her renewing and individual style unifies body and soul in an earthly bound love. It contradicts both the literary love ideal she emulates and the well-established Neoplatonic philosophy on love. Undoubtedly it makes her ‘unique among all others’”. (J. Vernqvist, “A Female Voice in Early Modern Love Poetry-Gaspara Stampa”, in TRANS. Revue de littérature générale et comparée, 15, 2013, p. 14)

Exploring the complexities of love from an unapologetically female perspective – as M.B. Moore writes, Stampa “boldly claims poetic equality with male masters” (M.B. Moore, “Body of Light, Body of Matter. Self-Reference as Self-Modeling in Gaspara Stampa”, in Desiring Voices: Women Sonneteers and Petrarchism, Carbondale, IL, 2000, p. 58) – Stampa’s own canzoniere thus ultimately investigates a vast array of ideas relating to personhood and creativity within a male-dominated tradition. “Repeatedly pointing to the act of writing, to its polyvocality and wit, and to the speaker's sex, Stampa's deixis constructs subjectivity. Conceits about artistic representation involving perception, matter, and imagination, for example, exemplify her female speaker's wit and knowledge of philosophical discourse, displaying an ingenuity expected only in male poetic geniuses. The content of these metaphors, furthermore, undermines the gendered dualism of master discourses that associate women with matter and chaos, men with spirit, form, and mind. Directed to an audience she defines at times as female, this witty display affirms women's complex subjectivity. Insofar as these poems' wit aims at erotic persuasion, Stampa also assumes that the gifts of mind and intellect that she represents may evoke rather that repel male desire. Wit becomes erotic lure”. (pp. 58-59)

Portrait of Gaspara Stampa, 1738, by Daniel Antonio Bertoli/Felicitas Sartori. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. Public Domain.

Though born in Padua into a wealthy bourgeois family (her father Bartolomeo was a jeweler), Gaspara Stampa grew up in Venice, in the area now known as Campo San Trovaso, where she moved with her mother Cecelia and two siblings Cassandra and Baldassare after Bartolomeo’s death, the family having relatives in the lagunar city. Stampa was afforded an excellent education initially under Fortunio Spira, a grammarian and poet, who taught her and her siblings Latin, grammar, and possibly Greek. They were also taught lute and voice by the musician Pierrissone Cambio. Gaspara was noted for her lovely singing voice by Girolamo Parabosco, organist at St. Mark’s in Venice and a composer, poet and playwright, who greatly praised Gaspara’s talents in his Lettere amorose (Venice, 1545, ll. 24v-25r). She would indeed become an excellent singer, musician, and songwriter in addition to her success as a poet.

Between around 1535 and 1540, the Stampa household became a salon of sorts, frequented by literary men like Girolamo Parabosco, Francesco Sansovino, Daniele Barbaro, Ludovico Domenici, Luigi Alamanni, Antonio Brocardo, Ortensio Lando, Sperone Speroni, and Benedetto Varchi. Conversation often turned to Petrarch and Petrarchism, the poetic imitation of work. It must have been a perfect milieu for Stampa, who undoubtedly learned a great deal about versification, meter, rhythm, cadence, imagery, form and rhyme from this period.

Early in 1544, Stampa’s brother Baldassare, a promising poet, died at the age of nineteen while at the University of Padua. His death precipitated a religious crisis for Stampa, whose fame as an artist seems to have already been growing (F.A. Bassanese, “Gaspara Stampa”, in Italian Women Writers, London, 1994, p. 405). In response to the death, Suor Angelica Paola de’ Negri, the abbess of the San Paolo Convent in Milan, sent a long letter to Stampa in an effort to comfort her and to urge her to abandon the world and retire to a convent. Instead of following Suor Angelica’s advice, Stampa re-entered the social scene, mingling with old friends and new acquaintances including Pietro Bembo's son Torquato, Giorgio Benzone, Girlamo Molin, Paolo Tiepolo, and Domenico Venier, and continuing her work as a singer and musician.

Portrait of Collaltino Collalto by Daniel Antonio Bertoli/Felicitas Sartori. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek. Public Domain.

On Christmas Day 1548, in Domenico Venier’s ridotto (salon), Stampa met count Collaltino di Collalto (1523-1569), a landed aristocrat and soldier from Friuli who was also a friend of many literati and a mediocre poet himself, though he is remembered now primarily as providing the fodder for Stampa’s great work. This fortuitous meeting began a tumultuous three-year love affair during which Stampa composed her canzoniere. For the most part, Collaltino ignored her advances, but Stampa nevertheless persisted in writing love sonnets for him. In May 1549, she enclosed 100 of these sonnets with a letter and mailed it to Collaltino, who was campaigning in France. Initially, Stampa’s mother and her sister hoped Collaltino would marry her, but the count’s unresponsiveness during this six-month absence dashed their hopes. After his return and a brief reunion with Stampa, he retreated to his estate in Friuli, leaving Stampa to doubt his love for her. In 1550 Collaltino took her to the estate, San Salvatore, but proceeded to ignore her while she was there. The same year, Stampa became a member of the Accademia dei Dubbiosi, using the pseudonym ‘Anaxilla’, ‘Anissilla’, or ‘Anassilla’, which Bassanese explains was “derived from the Latin toponym (Anaxum) for the Piave River, which flows through the Collalto estate in the Marche Trevigiane.” (F. A. Bassanese, “What's in a Name? Self-Naming and Renaissance Women Poets”, Annali d'Italianistica, 7, 1989, p. 105) Sadly, 1550 would also be the year of the poet’s first nervous breakdown, the beginning of a series of illnesses that would lead to her death.

Between 1551 and 1552, Stampa met Bartolomeo Zen, a Venetian patrician with whom she began a romantic relationship. In 1553, three of her poems were published in Il sesto libro di diversi eccellenti autori, edited by Girolamo Ruscelli. She would, however, fall ill again in 1554, coming down with a violent fever and dying within a fortnight. There were claims that she had committed suicide after learning of the plans of her former lover, Collaltino di Collalto, to marry Giulia Torelli.

Although Stampa produced at least 311 poems, the three sonnets published in 1553 were her only three compositions published during her lifetime. Nevertheless, her poetry seems to have been known to her contemporaries, and she herself is the dedicatee of numerous works praising her beauty and intelligence. The Rime also contains eight sonnets in praise of Stampa written by Benedetto Varchi (3), Giulio Stufa, Giorgio Benzone, Torquato Bembo (2), and Leonardo Emo.

While the vast majority of Stampa’s compositions included in the Rime were written in response to her relationship with Collalto, many are also addressed to noble personalities from her circle and to fellow poets, pointing up her unique position in these elevated circles.

Some of the content of Stampa’s writings in addition to its multiple male addressees have led historians to speculate as to whether the poet was also one of Venice’s famous courtesans (especially after the publication of Abdelkader Salza’s article in Giornale della letteratura italiana, 62, 1913, pp. 1-101), but to date no evidence has surfaced to definitively settle the issue. “Nevertheless, if she was not a courtesan,” Bassanese writes, “Stampa was certainly an ‘irregular’,” drawing on the term so incisively used by Eugenio Donadoni to describe her in his Gaspara Stampa: Vita e opere (Messina, 1919): “a female artist who existed on the fringes of polite society, accepted for her beauty and accomplishments rather than her bloodline or power.” (Bassanese, “Gaspara Stampa”, p. 405)

Counting among her more modern admirers is the German poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, who refers to Stampa in the first of his Duino Elegies:

“Aber die Liebenden nimmt die erschöpfte Natur / in sich zurück, als wären nicht zweimal die Kräfte, / dieses zu leisten. Hast du der Gaspara Stampa / denn genügend gedacht, daß irgend ein Mädchen, / dem der Geliebte entging, am gesteigerten Beispiel / dieser Liebenden fühlt: daß ich würde wie sie? / Sollen nicht endlich uns diese ältesten Schmerzen / fruchtbarer werden? Ist es nicht Zeit, daß wir liebend / uns vom Geliebten befrein und es bebend bestehn: / wie der Pfeil die Sehne besteht, um gesammelt im Absprung/ mehr zu sein als er selbst. Denn Bleiben ist nirgends” (Rainer Maria Rilke, Sämtliche Werke, Wiesbaden & Frankfurt a.M., 1955, I, pp. 685-6)

‘But, Nature, spent and exhausted, takes lovers back into herself, as if there were not enough strength to create them a second time. Have you imagined Gaspara Stampa intensely enough so that any girl deserted by her beloved might be inspired by that fierce example of soaring, objectless love and might say to herself, perhaps I can be like her? Shouldn't this most ancient of sufferings finally grow more fruitful for us? Isn't it time that we lovingly freed ourselves from the beloved, and quivering, endured: as the arrow endures the bow-string’s tension, so that gathered in the snap of release it can be more than itself? For there is no place where we can remain’.

References

E. Donadoni, Gaspara Stampa, Messina, 1919; M. Weston Brown, Vittoria Colonna, Gaspara Stampa and Louise Labé: Their contribution to the development of the Renaissance sonnet, New York, 1991; Edit 16, CNCE34706; Universal STC, 857433; M. Bianco, “Gaspara Stampa, Rime, Venezia, Plinio Pietrasanta, 1554”, in Petrarca e il suo tempo, Milan, 2006, pp. 535-537; F.A. Bassanese, Gaspara Stampa, Boston, 1982; F. A. Bassanese, “What's in a Name? Self-Naming and Renaissance Women Poets”, Annali d'Italianistica, 7, “Women's Voices in Italian Literature”, 1989, pp. 104-115; F.A. Bassanese, “Gaspara Stampa”, in Italian Women Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook, R. Russell, ed., London, 1994, pp. 404-413; D. De Rycke, “On Locating the Courtesan in a Gift of Song: The Venetian Case of Gaspara Stampa”, in The Courtesan’s Arts: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, M. Feldman & B. Gordon, eds., Oxford, 2006, pp. 124-132; J. Tylus, “Rescuing the Renaissance, Women Writers, Courtesans, and Salza’s Stampa”, in The Italian Renaissance in the 19th Century, L. Bolzoni & A. Payne, eds., Cambridge, MA, 2018, pp. 419-428.

How to cite this post

Fabrizio Govi, “One of the Greatest Female Poets of the Renaissance: Gaspara Stampa and Her Rime," PRPH Books, 22 September 2021, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/stampa. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.