Pignoria’s ‘Mensa Isiaca’ and Early Egyptology

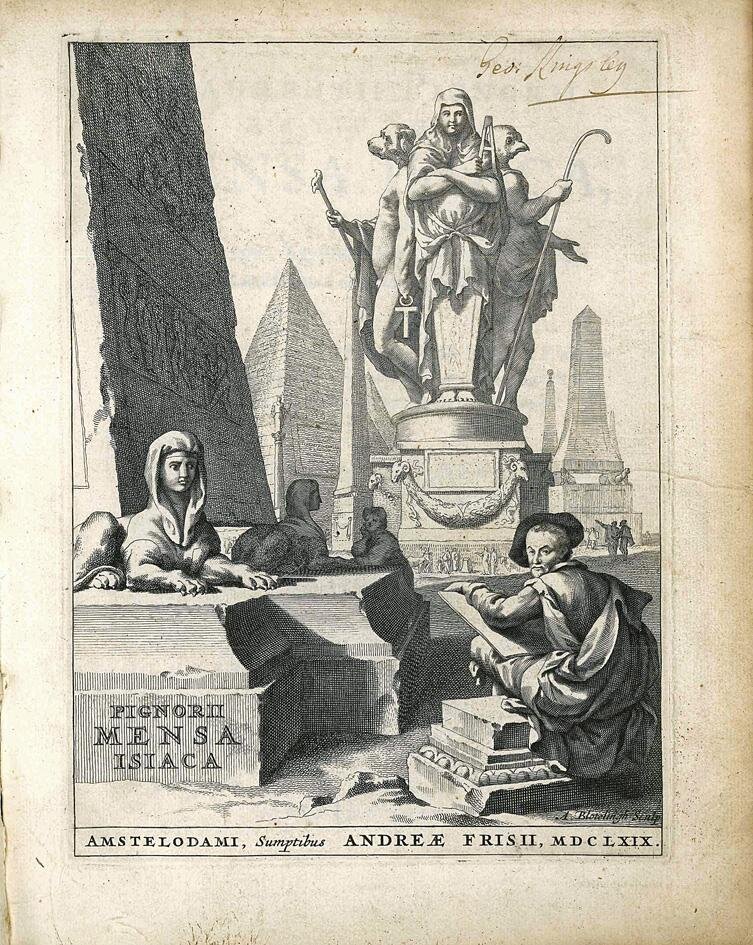

Detail of title page by Abraham Blotelingh, for Lorenzo Pignoria (1571-1631), Mensa Isiaca, qua sacrorum apud Aegyptios ratio & simulacra subjectis tabulis aeneis simul exhibentur & explicantur. Accessit ejusdem authoris de Magna Deum matre discursus, & sigillorum, gemmarum, amuletorum aliquot figurae & earundem ex Kirchero Chisletioque interpretatio. Nec non Jacobi Philippi Tomasini Manus Aenea, & de vita rebusque Pignorij dissertatio. Amsterdam, Andreas Fries, 1669.

This week’s post highlights the third and arguably best edition of an important treatise on the Mensa Isiaca by Paduan scholar, collector, antiquarian, and philologist Lorenzo Pignoria (1571-1631), which we are pleased to currently offer (see the full description of the available copy here).

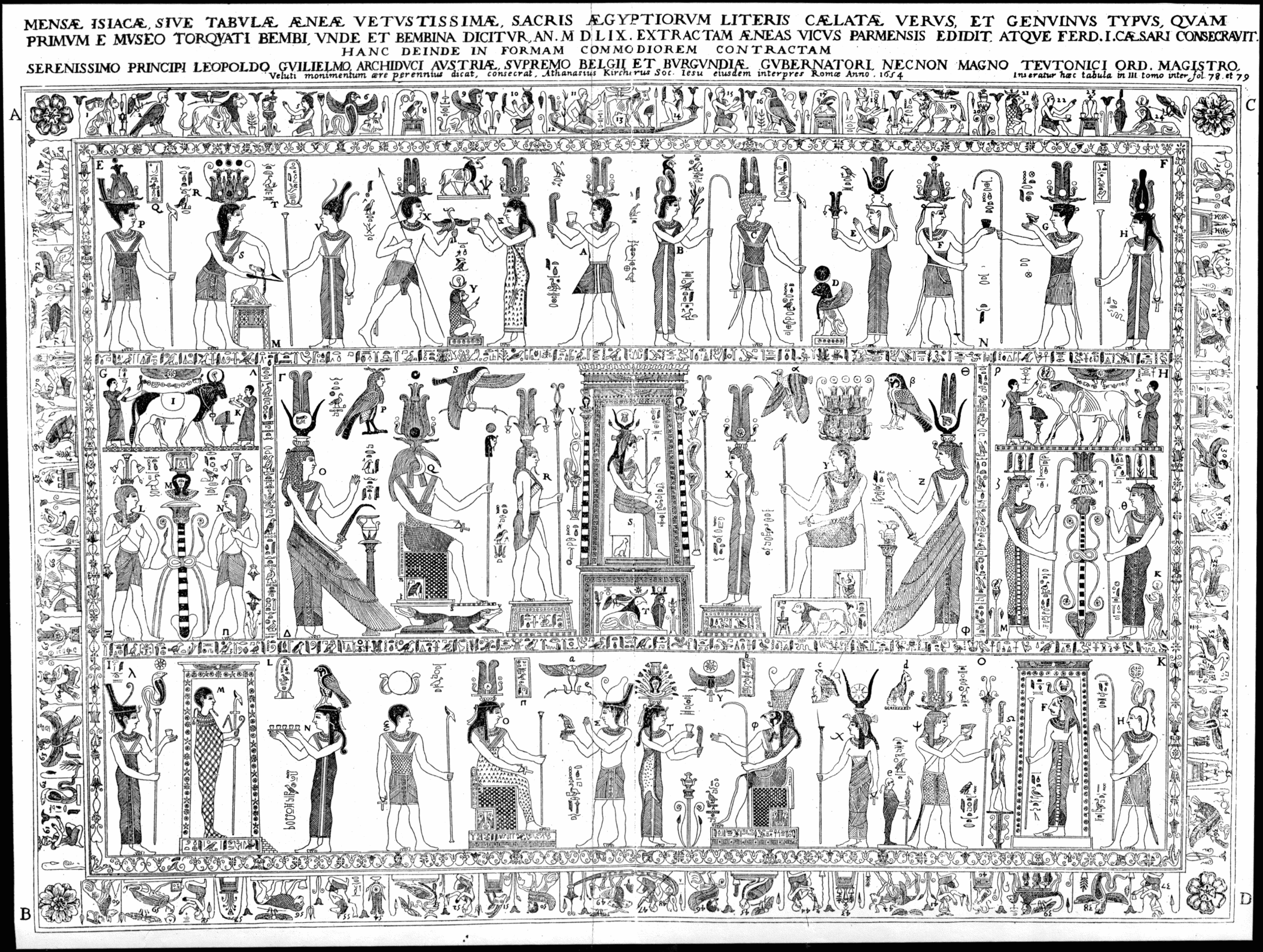

The 'Mensa Isiaca' or Table of Isis is a large, elaborate bronze tablet with enamel, copper, and niello inlay and bearing Egyptian cult scenes with figures of Isis (in the centre), Osiris, Thoth, Apis and other Egyptian deities. It is understood to have been discovered in the ruins of the Temple of Isis after the Sack of Rome in 1525 or 1527. After being acquired by the humanist scholar Cardinal Pietro Bembo, it also became known as the ‘Tabula Bembina’ or the ‘Bembine Table’; after his death in 1547 the Table passed to his son Torquato (1525-1595). It was later acquired by the Gonzagas and remained in their collections until the capture of Mantua in 1630. The table of Isis eventually came into the hands of Cardinal Pava, who gave it to the Duke of Savoy, who then presented it to the King of Sardinia. In 1797 the tablet was brought to Paris by French troops, and in 1809 – as Alexandre Lenoir attests – it was exhibited in the Bibliothèque Nationale. Later, it returned to Turin, and is now held at the Egyptian Museum of this city.

Fragment of the Mensa Isiaca. (Public Domain).

The Table was an object of fascination for Renaissance scholars, and appears in studies by such famous figures as Kircher, Montfaucon, Jablonski, and Caylus, but it was the humanist Pignoria who first provided a detailed printed account of the object in this very work, the first scholarly work on Egyptology, which first appeared in Venice in 1605, under the title Vetustissimae tabulae aeneae sacris Aegyptiorum.

Pignoria’s treatise is grounded in the object itself. He considered the hieroglyphs on the Table to be incomprehensible (a correct assessment, as it turns out, as they are in fact nonsensical, but this could only be fully determined after 1822, when Jean-François Champollion deciphered hieroglyphs using the Rosetta Stone, which had been found by Napoleon’s troupes in 1799) and was careful to avoid symbolic or allegorical interpretations—the dominant trend for investigations of ancient cult objects at the time—as he explains to the reader:

I will explain the images of this table, not allegorically, but, to the best of my ability, faithfully following the ancient narratives [ad veterum narrationum fidem]. For I, more than anyone, hate those excessive and usually irrelevant interpretations of this kind of material, which the Platonists, departing from their master’s teaching, have imposed to shore up their tottering fables. And I thought it better to confess my ignorance rather than annoy my learned reader.” (trans. D. Stolzenberg, Egyptian Oedipus, p. 59)

Pignoria thus relied instead on what he could observe directly from the object in comparison with classical texts, inscriptions, amulets, carved gems, coins, and statuettes, but always with caution and by considering individual figures and portions rather than offering a holistic interpretation of the Table’s overall significance. “Pignoria was,” as Stolzenberg notes, “willing to hazard an interpretation of the table’s symbols, but his identifications of individual figures were explicitly tentative, and he did not attempt to explain how they related to one another semantically” (Stolzenberg, Egyptian Oedipus, 46).

His tentativeness, learned background, and detailed object study proved fruitful: contrary to the widely held belief at the time that the Table was a mystical relic from the dawn of creation, Pignoria concluded that the Table was a Roman work of the Augustan period. This is in line with current assessments that date the creation of the Table to Rome in the first century AD.

The origin and significance of the Mensa Isiaca is still subject to debate, although Pignoria's explanation long proved the simplest and most convincing: he believed it was a representation of sacrificial ceremonies according to Egyptian rites. Though the scenes are Egyptianising, modern scholars agree it was produced in Imperial Rome, probably for use in the Temple of Isis.

Nonetheless, in the seventeenth century the Table, having become one of the most famous Egyptian artifacts known, was central to a host of mystically bent theories. It was so used, for example, by the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher as a primary source for deciphering hieroglyphs in his Oedypus Aegyptiacus (1652/55), which included the below illustration based on the illustrations included in Pignoria’s own work. In contrast to Pignoria’s emphasis on the Table as an archeological object, Kircher’s account gave an allegorical understanding of hieroglyphs that situated Egypt as a source of ancient mystic or occult wisdom.

The Bembine Table of Isis from Kircher’s Oedypus Aegyptiacus, reprinted in Manly P. Hall’s The Secret Teachings of All Ages (1928).

Given Pignoria’s reliance on visual details, illustrations were critical to the work, which would indeed become a great success, following the trajectory set by the Table itself. The popularity of the Table had begun to spread in 1559 after the Parma engraver Aeneas (or Enea) Vico (1523-1567) published a large engraving of it which he had executed e Musaeo Bembi that same year. Vico’s illustration was to scale, having presumably traced the actual Table. Granted a ten-year privilege, the illustration appeared under the title Vetustissimae Tabulae Aeneae but without any other historical information.

Vico’s engraving forms the basis for the illustrations by Giovanni Franco included in the 1605 publication. In 1600, Franco had copied the plates on a smaller scale and sold them as a collection of 12 prints, 11 folding plates that together make up the entire Isis Tablet plus a title-page. The plates were included, variously assembled and folded, and in varying numbers, in a handful of copies (probably deluxe versions) of the first edition published by Franco in 1605.The edition also includes in-text illustrations and five supplementary plates of antiquities, primarily gems, unassociated with the text. A second edition of Pignoria’s work, undertaken by Johann Theodor and Israel de Bry, appeared in Frankfurt in 1608, with a slightly larger illustration of the Table. (Whitehouse, Documentary culture, p. 70)

One of 11 folding engravings included in the 1669 edition of Pignoria’s Mensa Isiaca.

It was not until the 1669 edition, however, that Pignoria’s text could be considered in its greatest glory. By that time the Paduan had passed away, having succumbed to the plague on June 13, 1631, but his too-brief career was nonetheless rich and diverse, and he left an important and influential humanist legacy. After returning to Padua following his stay in Rome in the early 1600s, he had become parish priest of San Lorenzo. The chair of letters in Pisa was soon offered to him through Galileo Galilei, but he refused it in order to devote himself to his studies. These proved numerous and wide-ranging, including annotated editions of the most important emblem books (like Alciati’s Emblemata), interpretations of Roman frescoes, and texts on the gods of Mexico, Japan, and India, with which he effectively extended sixteenth-century mythography beyond the European context. Always with an empiricist angle, these works offered an important alternative to the standard classical narratives then in circulation. His 1625 work L’Antenore is dedicated to the mythical founder of Padua, whose tomb was in his church, and in 1630 he obtained a canonical office in Treviso. Pignoria was also a great collector, whose collection included paintings, portraits, inscriptions, coins, medals, ancient tools, weights, fibulae, oil lamps, amulets, and keys, and had a widely admired museum. In other words, Pignoria was the perfect candidate for the publishing project of one Andreas Frisius (or Fries; 1630-1675) which was soon to be underway.

Frisius’s first printer’s device encapsulates his principal objectives based on the retrieval of information from the past. Under a Moses-type figure handling a number of large books reads the phrase ‘Optimi consultores mortui’, that is, “The best counselors are (the) dead”. The Belgian bookseller and printer, whose first works appeared in 1664, was dedicated to publishing learned, scholarly books. He felt it was important for the modern world to retrieve information from the Roman world and was particularly interested in reprinting works by later humanists, especially by Italian authors, though always in Latin, as Pignoria’s text is presented here. Frisius approached these editions with an emphasis on an exceptional degree of accuracy and he also placed great effort on including many illustrations throughout.

The full-page engravings and numerous vignettes in the 1669 edition of Pignoria’s work are no exception. Here Frisius reproduced the exceedingly rare woodcut illustrations from the first edition, which, as noted, generally did not appear together with the text, and he also includes a wonderful engraved frontispiece by the well known Abraham Blotelingh (more commonly Blooteling; 1640-1690).

Numerous other illustrations are also included in the important texts Frisius chose to include after the original work: an index with commentaries on ancient amulets by Kircher and Jean Chifflet; Pignoria’s Magnae Deum matris Idaeae, introduced by a separate title-page and addressing the Roman cult of the goddess Cybele and the god Attis; a description of the bronze hand used in the cult of Cecrops written by Giacopo Filippo Tomasini (1597-1654); and Tomasini’s De vita, museo et bibliotheca Pignorii (1669/1670), devoted to Pignoria’s work and library.

This third edition therefore offers a substantial augmentation both in terms of textual and visual information, as compared to the first and second editions of Pignoria’s Mensa Isiaca, placing various scholars and images in dialogue with one another. In presenting the text this way, Frisius is able to complement the strengths of the original work in a way that effectively transmits its own significance to a new generation of learners, greatly expanding on the reader’s ability to understand and appreciate Pignoria’s careful study and to contextualize it in terms of the by-then growing field of Egyptology.

Brunet, IV, 653; Graesse V, 290; Caillet 8681; Blackmer 1312; Gay 1567; Ibrahim-Hilmy II, 119; Philobiblon, One Thousand Years of Bibliophily, no. 213; H. Whitehouse, Documentary Culture: Florence and Rome from Grand-Duke Ferdinand I to Pope Alexander, Bologna 1992; D. Stolzenberg, Egyptian Oedipus. Athanasius Kircher and the Secrets of the Antiquity, Chicago-London 2013; M. Buora, “Pignoria, Lorenzo”, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani 83 (2015); I. Maclean, Episodes in the Life of the Early Modern Learned Book, Boston 2020, esp. ch. 5, “Andreas Frisius (Fries) of Amsterdam and the Search for a Niche Market, 1664–1675”.

How to cite this information

Julia Stimac, “Pignoria’s ‘Mensa Isiaca’ and Early Egyptology,” PRPH Books, 11 November 2020, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/pignoria. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.