Gasparo Gozzi’s Favole Esopiane in a Changing Venice

Gozzi, Gasparo (1713-1786). Favole esopiane di Gasparo Gozzi pubblicate nelle nozze Da Mula – Lavagnoli. Venice, Stamperia Pinelli, 1809. See a description of this copy here.

In 1809, Jacopo Morelli and the Pinelli press paired up to print an edition of Gasparo Gozzi’s Favole esopiane on the occasion of the marriage of Elena Lavagnoli and Antonio Da Mula. A special copy of this edition, printed on blue paper, is presented here (see the description of this copy here). We learn in the first prefatory text – addressed to the groom’s father, Andrea da Mula, and written by one Paolo Boscoli – that the edition was published on the recommendation of Morelli himself, who was also responsible for the editing. Gasparo Gozzi had, however, passed away over two decades earlier, prompting our curiosity about Morelli’s decision. In fact, as the latter states plainly in his own preface, he was a great admirer of Gozzi, whose reputation as an esteemed writer, critic, journalist, and intellectual was by then firmly established. Moreover, the nature of the Fables would have widespread appeal, appropriate for a marriage celebration. Nevertheless, the timing of the publication in the years after the fall of the Venetian Republic lend to his decision a particular poignancy that is worthy of unravelling.

Gasparo Gozzi (1713-1786) was born in Venice to a noble family who had lost their wealth. He was the first of 11 children, including the well-known playwright Carlo Gozzi (1720-1806). In 1739, Gasparo married the formidable Luisa Bergalli (1703-1779). He was 25 and she 35 – a particularly dramatic age gap for the time, and with the additional differences in their social statuses (she being of humbler origins) – the union did no favours to Bergalli’s legacy, despite the fact that she was a remarkable poet, anthologist, translator, and playwright. By the time of their marriage she had already published an important anthology of female poets, two dramas, and a comedy, and would go on to produce translations of Terence, Racine, and Molière, while also remaining devoted to poetry. Although Gozzi’s own family encouraged literary endeavors, Bergalli clearly had a great influence on his work, and the two collaborated on several efforts.

Francesco Bartolozzi, Portrait of Gasparo Gozzi, ca. 1757, from Gasparo Gozzi, Opere in versi e in prosa (Venice, Occhi, 1758). Image from Rijksmuseum, Netherlands, CC0.

Venetian school, Luisa Bergalli as the Arts, ca. 1735. Public domain.

Indeed, the couple were extremely prolific, yet despite this tremendous output they had ongoing financial hardship (it didn’t help that they had five children). In an effort to mitigate these difficulties, Gozzi produced an extremely large number of encomiastic texts for patrician celebrations, which often paid handsomely. One fine example is none other than a cantata that he wrote for the 1755 wedding of Marco Andrea Pisani and Caterina da Mula, for which he was given twenty zecchini – roughly a quarter of the annual salary he would make some two decades later in a government position, at the height of his reputation. (Piero Del Negro, “Gasparo Gozzi e la politica veneziana,” in in Gasparo Gozzi: Il lavoro di un intellettuale nel Settecento veneziano, Padova, 1989, p. 58) These works seem to have mainly been done for the money, rather than any personal relationships with the families, and it is as yet unclear if there was any relationship between the Da Mula and Gozzi families. The Favole esopiane were, however, not composed with such an occasion in mind.

Nicolas de Largilliere, Portrait of Edmé Boursault. Public domain.

Gozzi’s association with Aesop’s famous fables traces back to the later 1740s, when he translated and adapted two plays by Edmé Boursault (1638-1701), Esope à la ville (1690) and Esope à la cour (1701). These were moralistic heroic comedies presented as a series of episodes rather than a continuous narrative. In the first, Esope à la ville, Aesop serves as an advisor to Learchus, a governor under King Croesus, and uses fables as satirical responses to questions about romance. Moral satire develops further in the second, Esope à la cour, in which Aesop appears as King Croesus’s Minister of State and addresses such topics as religion along with the hypocrisy and vice permeating the royal court. The court in question was ostensibly that of King Croesus, but in reality that of Louis XIV. Not surprisingly, the play was held up by censors and only performed after Boursault’s death.

Gozzi freely translated and altered Boursault’s works, omitting sections and inserting certain apologues of his own, and they were presented on the Venetian stage in reverse order: Le Favole di Esopo alla Corte in 1747 and Esopo in città in 1748. Interestingly, one of the changes he made to Esopo alla Corte suggests a challenge to the contemporary norm of marrying for combined profit or according to the will of the parents. (Antonio Zardo, “Esopo in Commedia,” Nuova Antologia, CLVI, Rome, 1911, p. 211).

Venice’s Teatro S. Angelo. Closed in 1803, the theatre was changed to a warehouse and then demolished.

They didn’t appear on just any Venetian stage, however. Gozzi and Bergalli had undertaken the management of Venice’s Teatro S. Angelo theatre between 1747 and 1748, during which time they worked busily to translate, adapt, and produce several works for the stage, mostly of French origin, including Gozi’s two Aesop-inspired plays. The couple’s work at the Teatro S. Angelo was, in the end, a great commercial failure that only added to their ongoing financial hardships, but such was the success of Le Favole di Esopo alla Corte in particular that, as their son, Francesco, wrote in his unpublished memoirs, for an instant it seemed there was hope to the doomed enterprise. (A. Zardo, “Esopo in Commedia,” p. 204).

While Esopo alla Corte may have been the most popular, Gozzi scholar Antonio Zardo praises the elegance of both plays, citing them as the most important among the theatrical compositions Gozzi derived from the French (p. 204).

Aesop’s fable of the Fox and the Crane, from Jacques Bailly's Le Labyrinthe de Versailles. Public domain.

Stylistic innovation was a major appeal of the fable genre. Although the popularity of Aesop’s fables obviously dates back to Aesop himself (ca. 620 BCE - 564 BCE), his recited stories were only collected for the first time three centuries after his death and enjoyed renewed popularity in the Middle Ages and again in the eighteenth century. The latter resurgence built off the popularity of the French translations made by Jean de La Fontaine (1621-1695) of a wide selection of fables between 1668 and 1694, especially those of Aesop but also others of more diverse origins. Interest in fables then flourished in Europe, especially in France, Italy, Spain, England, and Germany, with a wide array of fabulists keen to exploit and develop the flexibility of the genre. Many worked with the established canon of stories, while others wrote their own fables.

As the content of Gozzi’s plays demonstrates, the fables have traditionally been meant for adults, but from the Renaissance on they could be for children as well. Notably, the education of the young Dauphin may be behind the 39 fountains with stories from Aesop’s fables placed throughout the Labyrinth garden at Versailles. Thus fables gained a variety of functions, ranging from rhetorical exercises and ethical instruction to vehicles for social or political satire and indeed as a literary form of its own, as they are here. (Kenneth McKenzie, “Italian Fables of the Eighteenth Century,” Italica XII, 1935, p. 39). Operating within an established set of conventions and narratives, one could infuse the fables with great style and personality, as Gozzi did here with a gently moralizing and witty playfulness that would come to characterize much of his work.

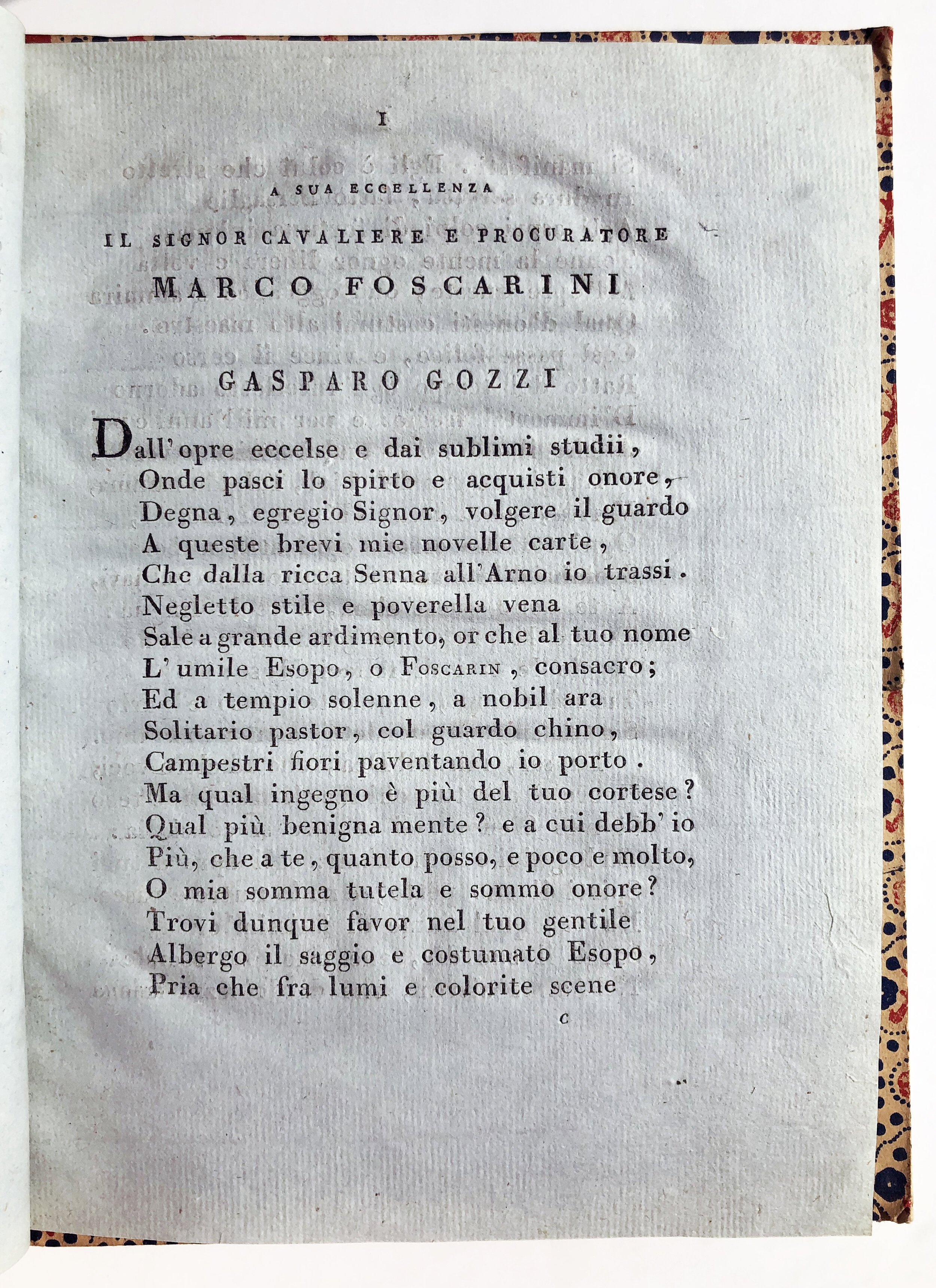

In 1747 and 1748, both of Gozzi’s plays were printed anonymously by Pietro Bassaglia, and they were not included in the collected edition of Gozzi’s work published in Venice by Bartolommeo Occhi in 1758. As such, they fell into a momentary state of oblivion but finally reappeared in the present edition, reworked in several places, with the prose text “Ad Apollo” in defense of allegory and the poetic epistle with which Gozzi had initially dedicated Esopo in città to Marco Foscarini (1696-1763). Although observing their French origin, Morelli seems to have been (understandably) somewhat confused at the genesis and development of the works which, as he explains in the preface, he found in a single manuscript derived “dalla ricca Senna all’Arno,” and which he, Morelli, had “gelosamente guardato.”

As he relates in the preface, Morelli was primarily motivated by the literary value of Gozzi’s Favole and their broad appeal, and felt it was important to make sure such work was saved for posterity. One can’t help but think, however, that the changing tides of Venice might have added some urgency to this desire for publication and preservation.

Gasparo’s brother Carlo, whom Morelli also greatly admired, had died three years earlier, marking the end of an era for the Venetian stage, particularly because of his association with commedia dell’arte. The term for this Venetian legacy probably comes from Carlo Goldoni (1707-1793), who in fact took over stage management of the Teatro S. Angelo soon after Gozzi and Bergalli left. For Goldoni, the problem faced by Italian theatre at that moment was in its lack of realism. Commedia dell’arte had thrived in the seventeenth century, but by the eighteenth its reliance on stock figures and scenarios, and increasingly “slapstick” humour, had made it feel tired and stereotypical. Over the 1750s he initiated a reform of Italian comedic theatre that eventually led to the demise of the older tradition, replacing it instead with scripted, realistic works of naturalism more in line with Enlightenment values.

Alessandro Longhi, Portrait of Carlo Goldoni, ca. 1757. Ca Goldoni Venezia, Venice. CC 4.0.

Frontispiece portrait of Carlo Gozzi in Carlo Gozzi, Le fiabe di Carlo Gozzi, volume I, Bologna, Nicola Zanichelli, 1884.

It was in the 1760s that Carlo Gozzi distinguished himself as a playwright of fiabe drammatiche or “fairy tales for the theatre” in direct response to Goldoni’s work. These were sophisticated works of fantasy that incorporated commedia dell’arte figures and extended the genre of the fairy tale. Fantastically creative, they brought him great acclaim, and were popular in Italy and abroad, particularly in Germany, where Goethe, Schiller, Lessing, and Schlegel all counting among the admirers of his work. Carlo Gozzi thus stood as a champion of traditional Venetian theatre, which received a final blow in 1797 when Napoleon outlawed masks and banned Commedia dell’arte outright. The same year, 1797, saw the burning of the Libro d'Oro della Nobiltà Italiana (The Golden Book of Italian Nobility).

Carlo’s traditionalism in some ways mirrored Gasparo’s own. In 1747, the same year Gasparo and Luisa took over the theatre, the two brothers became founding members of the Accademia dei Granelleschi. This group, patronized by the young Venetian patrician Daniele Farsetti, was dedicated to preserving the purity of Italian literature against French influences. The academy mostly produced anonymous burlesque poetry, but it also championed Dante, whose Tuscan writing was upheld as a model. In fact, Gasparo Gozzi became a great champion of Dante, defending the poet against the criticism of Saverio Bettinelli (1718-1808) in his Giudizio degli antichi Poeti sopra la moderna censura di Dante… (Venice, Antonio Zatta, 1758), doing much to shape the poet’s reputation in the following decades. It is also Gozzi who is responsible for the summary triplets for each canto of the Comedy in the Zatta edition of 1757 (see a description of this work here; Domenico Consoli, Enciclopedia Dantesca, 1970).

Gozzi’s “Argomento” in Dante Alighieri, La Divina Commedia di Dante Alighieri Con varie Annotazioni, e copiosi Rami adornata... Tomo Primo [- Terzo]. Venice, Antonio Zatta, 1757. [Together with:] Idem. Prose, e rime liriche edite, ed inedite di Dante Alighieri, con copiose ed erudite aggiunte... Tomo Quarto Parte Prima [- Seconda]. Venice, Antonio Zatta, 1758. See a description of this copy here.

The major difference between the brothers’ traditionalism is that while Carlo’s conservatism kept him closed off and deeply opposed to any and all areas of reform, Gasparo’s was aimed at upholding a certain level of literature but still allowed for a curiosity and openness to the possibility that the new might also be good. Indeed, another of the innovations he included in the Favole was the suggesting a new kind of theatre, one that wasn’t distracted by “silliness” and that could be a source of virtue for the public (A. Zardo, “Esopo in Commedia,” p. 211).

Gozzi was also deeply interested in contemporary life and made important contributions to the development of journalism in the eighteenth century with his La Gazzetta Veneta (1760-1762), a chronicle of life in Venetian society, Il Mondo morale (1760), a moralistic serial novel of sorts that was published over nine months, and L’Osservatore Veneto (1761-62), a review of philosophy, theatre, and literature that was modeled on Joseph Addison and Richard Steele’s The Spectator.

Angelo Giordani, Bust of Gasparo Gozzi, 1847. Part of the Panteon Veneto preserved at the Palazzo Loredan di Campo Santo Stefano. Image courtesy of the Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti.

Much of this was financed through the connections of Foscarini, who briefly served as Doge in the last year of his life and whom Morelli remembers fondly in the preface of the present edition. Gozzi served as Foscarini’s secretary as of 1752 and with him worked on a major compilation of Venetian literature, Della letteratura veneziana, of which only the first volume was published (Padua 1752). To help Gozzi deal with his financial situation Foscarini had him appointed to transcribe the catalog of the Biblioteca Marciana in 1754, although the two ultimately had a falling out around 1760 when Foscarini made it impossible for Gozzi to achieve the University chair he had so long desired. Nevertheless, Foscarini’s and Gozzi’s mutual dedication to Venice’s cultural legacy would have appealed to Morelli, whose own Dissertazione storica della pubblica libreria di san Marco a Venezia was published in 1774, just a few years before he named librarian of the Marciana in 1778.

Giuseppe Soranzo, Bust of Jacopo Morelli, 1891-1892. Part of the Panteon Veneto preserved at the Palazzo Loredan di Campo Santo Stefano. Image courtesy of the Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti.

The last decades of Gozzi’s life also saw the rise of his station. Famous for his literary work and thoughtful criticism, he was appointed to several public offices for the University of Padua and for the Venetian Republic, in which role he wrote three major reports on the state of printing in Venice. Between 1770 and 1775 he also worked on reforming the education system, but the period was characterized with significant depression and poor physical health. He spent his final years in Padua where he died in 1786.

Gozzi was, as Piero del Negro writes, “halfway between the old and the new” (P. del Negro, “Gasparo Gozzi e la politica veneziana,” p. 51), and the particular mix of tradition and openness embodied by the famously poor count must have felt especially meaningful to the scholarly Morelli, now “Royal Librarian” under Napoleon I.

In reality the Republic had long been in decline. Talk of its “decadence,” oligarchy and seemingly problematic political neutrality heightened in the years leading up to 1797, and attempts at political reforms from within were tamped down as secrecy and repression came to characterize Venice’s reputation. Indeed, this is why the young Ugo Foscolo (1778-1827) originally hailed Napoleon as Venice’s saviour: in his A Bonaparte liberatore of 1797, he expresses his hope that the French would overthrow the Venetian oligarchy then in control of his beloved homeland. But with the Treaty of Campo Formio, signed in October of that year, Napoleon handed Venice over to the Austrian Empire and everyone felt betrayed, conservatives and progressives alike. The city was taken back from Austria with the Treaty of Pressburg, signed in 1805, when it became part of Napoleon's Kingdom of Italy, and would return once again to Austria following Napoleon’s defeat in 1814. After a millennium of self-governance, it would have been impossible not to feel confusion and a certain longing for stability, and for Morelli, protector of Venetian literature, to feel a keen desire to promote the nobility of La Serenissima’s own cultural legacy.

Editor’s note: This is an updated version of a previously published article.

How to cite this information

Julia Stimac, “Gasparo Gozzi's Favole Esopiane in a Changing Venice,” PRPH Books, 1 June 2022, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/gozzi-favole. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.