On Fortune-Telling Books: A Spirito Incunable and Two Later Manuscripts

The first printed fortune-telling book: Lorenzo Spirito’s Libro da la Ventura [Bologna, Caligola de Bazaleriis, 1498-1500].

See the full description of this copy here.

Fortune-telling books (also called books of fate, lottery books, or divination books) flourished in the Medieval and early modern periods. Generally beginning with a set of pressing questions, these “game” books revolved around oracles—derived from either antiquity or from more contemporary sources—which the reader-player followed to discover “answers” and reveal their fate. The books worked on chance and often required the use of dice or other moving parts such as volvelles. As such, they were extremely interactive objects, and provide fascinating insight into an “everyday” form of engagement with chance, ritual, and fate during this period.

The historical practice of bibliomancy—divination by way of books—is one of the main precursors of fortune-telling books. In Roman antiquity, Sortes Homericae, Sortes Virgilianae, and Sortes Sanctorum were among the most popular forms of sortilegium or sortes, (i.e., sortilege—divination by drawing lots), with one’s fortune being told through randomly chosen passages in the works by Homer, Virgil, and in the Bible, respectively. Socrates is even said to have performed such sortes when he predicted his own death via a passage in the Iliad.

Sortes remained popular until the Middle Ages and provide important foundations for fortune-telling books, but the latter’s subsequent development is in fact multi-faceted, drawing on a variety of established and emerging systems of belief. The “hands on” devotional and art practices of the late Medieval period, for example, helped shape the “interactive” nature of the books (S. Karr Schmidt, "Art—A User’s Guide: Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance," ch. 1). Medieval astrological prophecy and numerical games (possibly originating with ancient dice oracles in Asia Minor) were also of great import, as were emerging mathematical studies of the Renaissance. (A. L. Palmer, “Lorenzo ‘Spirito’ Gualtieri’s Libro delle Sorti,” p. 575). Palmer also notes the changing tone and emphasis on fate and fortune evident in Renaissance literature, “from Dante’s initial explanation that fortune was the will of God to Boccaccio’s observation that Fortune was not necessarily blind and unpredictable, to Machiavelli, who in his Il Principe…noted that virtue and wisdom can temper fortune, and therefore a wise ruler could shape certain aspects of his destiny” (Palmer, “Lorenzo ‘Spirito’ Gualtieri’s Libro delle Sorti,” p.562-64).

Lorenzo Spirito’s Libro da la Ventura

The first printed fortune-telling book was the Libro da la Ventura by Perugian poet Lorenzo Gualtieri, better known as Lorenzo Spirito (ca. 1425-1496). Spirito composed the book no later than 1482, the date of the original manuscript preserved in the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice (ms 6226), and it was first published in Perugia that same year. Spirito’s Libro was also the most popular representative of the genre in the early modern period and was frequently reprinted over the sixteenth century; in Italy, more than a dozen editions were already printed by 1525 and at least 36 by 1560, and over two dozen more editions were produced in French, Spanish, English and Dutch by the end of the seventeenth century.

Only one copy of the Perugia edition of 1482 is known, this being held at the Ulm Stadtbibliothek, and only three other fifteenth-century editions are recorded, these having appeared in Vicenza, Brescia, and Milan.

Title page of Lorenzo Spirito’s Libro da la Ventura [Bologna, Caligola de Bazaleriis, 1498-1500].

“La più antica delle edizioni bolognesi note deve essere quella senza data, impressa con i caratteri di Caligula Bazalieri [...] Essa era rimasta fino ad oggi sconosciuta e l’esemplare apparso alla vendita Sotheby è probabilmente unico.”

PrPh is now pleased to offer the only known copy of a Bolognese incunable edition of Spirito’s Libro, which once belonged to the great Italian bookseller Tammaro De Marinis. This undated edition of the Libro della Ventura—not recorded in ISTC—is attributed to the Bolognese printer Caligola Bazalieri, who was active in the city from 1490 to 1504 and who focused his production on popular texts in the Italian vernacular. Caligola employed the same roman font used in this copy for his edition of the Regula of St. Jerome, which appeared in Bologna on 28 March 1498 (see GW 12466), while the title on the opening leaf is set in the same type 140G that he used for the Lucidario printed on 15 April 1496 (see BMC vi, 837). The printing of the present book can therefore likewise be dated to the last years of the fifteenth century.

Another revealing clue for the possible dating of this Bolognese publication is in the inscription 'PIERO CIZA FE QVESTO INTAIGIO' visible on the columnar borders framing the plates on fols. A2r-A4r, implying that the block cutter Pietro Ciza was responsible for the remaining illustrations. The name of Ciza (also known as Cisa or Chiesa) is found in a Bologna Calendario of 1493 and in the famous Viazo da Vanesia al sancto Jherusalem of 1500. The same blocks were mostly re-used in the Libro della Ventura printed in Bologna in 1508 by Justiniano de Rubeira, whose unique and incomplete copy is in the Biblioteca Marciana.

Illustrations

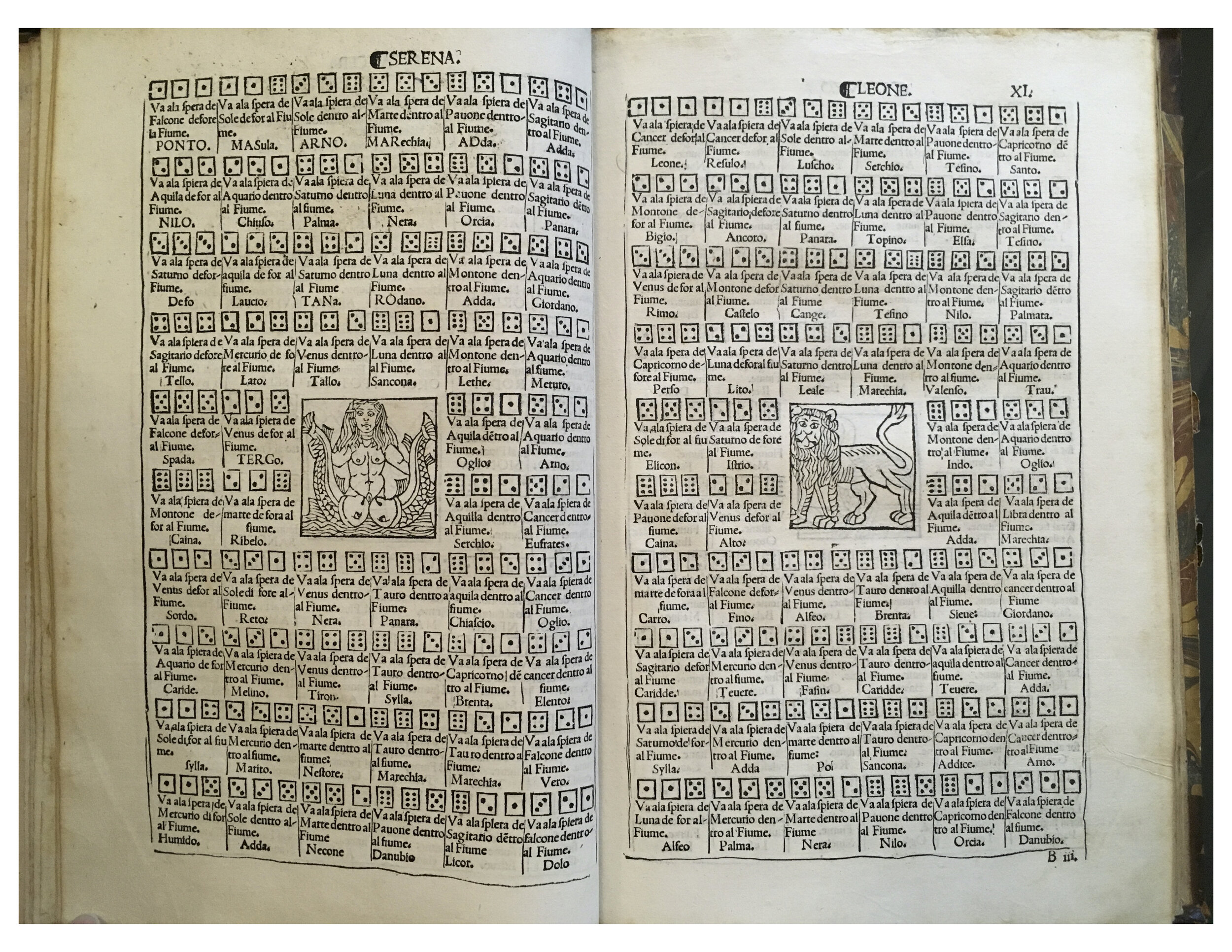

The volume is extensively illustrated, as are all books of this kind. An elaborate full-page woodcut on fol. A2r presents the fortune-telling method contained within the book along with short explications. This is followed by five full-page woodcuts, each depicting four seated Kings set within richly decorated architectural border; a series of woodcut diagrams showing different combinations of dice throws—each with a small vignette at the centre; and full-page woodcuts depicting the spheres and set within frames bearing floral motifs and putti. The volume concludes with lists of prophecies which include more vignettes of kings and prophets.

The reader first encounters the wheel of fortune which is surrounded by four figures and a set of fortune-related questions the book will go on to answer. According to the player’s chosen question, they are to go to one of the represented kings …

… and are subsequently referred to a specific astrological sign and related plate of dice. The player rolls three dice and matches the roll to the outcome listed on the page to determine what river they must travel to next.

The rivers are located on the edges of “spheres” characterized by a classical deity or another motif. Each sphere’s dial corresponds to a prophet’s name and number…

…these refer to the last section of the book, where “answers” are revealed via prophets whose words are articulated through terzine.

The variety of illustration is indicative of fortune-telling books in general, which typically included, in addition to various tables and diagrams, astrological and animal signs and imagery, along with prophets, kings, and philosophers, and comparatively little text. This raises an interesting point of accessibility: on one hand, the vast and varied imagery requires no specialized knowledge on the part of the reader-player and is thus fitting for the “strictly” aleatory nature of the book—one need only bring dice to the game in order for the future’s secrets to be revealed. On the other hand, the great variety and depth of the sources in evidence would add another level of enjoyment for those who were more familiar with the figures in play.

Their extensive illustration is arguably at least partly why fortune-telling books became so popular in the first place, and why Spirito’s Libro set such a strong precedence for others to follow: “In the late medieval and Renaissance periods, the growth of the lottery book as a variety of bibliomancy appears to have been strongly linked to its pictorialization, first in manuscript and, eventually, in print. The Losbuch [the German term for the book of fate] thus comprised a major instance of the increasingly visual configurations of aleatory forms in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Images constituted a defining element of their role as mediators of fortune and future time, and it was the construction of the book as not only a physical object but a pictorial one that was central to framing users’ experience of chance.” (J. Kelly “Renaissance Futures: Chance, Prediction, and Play in Northern European Visual Culture, c. 1480-1550,” p. 43)

Game Play

Upon starting the game, the reader-player first encounters the wheel of fortune which is surrounded by four figures and a set of fortune-related questions the book will go on to answer. According to the player’s chosen question they proceed to one of the represented kings and are subsequently referred to a specific astrological sign and related plate of dice. These plates are full-page tables indicating all possible combinations of dice rolls. The player then rolls three dice and matches the roll to the outcome listed on the page to determine what river they must travel to next. The rivers are located on the edges of “spheres” characterized by a classical deity or other motif. Each sphere’s dial corresponds to a prophet’s name and number to which the player, upon locating the correct river, is directed to for their question’s ultimate answer. In effect, the game is quite elaborate:

“The rules of the game seem designed to interpolate as many steps as possible before and after the throw of the dice which determined which of the 56 verses shall be accepted as an 'answer'. Thus the inquirer anxious to know if he will be cured of a disease is referred first to King Pharaoh, and from Pharaoh to the sign of the Ostrich. He then throws his 3 dice, and (let us say) turns up three 'aces' (e.g. ones). On this he is referred to the sphere of the Leopard and the River Po. These give a reference to the prophet Jonah, Verse I, and in this he finds his answer” (A.W. Pollard, Italian Book Illustration and Early Printing, A Catalogue of the Early Italian Books in the Library of C.W. Dyson Perrins, no. 187).

If the rules seem difficult to follow it’s because they are. In addition to the aleatory nature of casting dice, the elaborate game play creates a flexible, evolving structure of interaction while enhancing the quality of suspense. As Justyna Kiliańczyk-Zięba notes, “One common feature [of fortune-telling books] was an apparently complicated structure designed to mystify the readers…Searching for references was intended to build excitement and suspense, and to keep the enquirer in a state of uncertainty about the result of divination.” (J. Kiliańczyk-Zięba, “In Search of Lost Fortuna,” p. 122).

The initial Wheel of Fortune in Spirito’s Libro da la Ventura [Bologna, Caligola de Bazaleriis, 1498-1500]. Here the reader-player must choose which question to ask, which in turn decides which king they must “follow.”

Spirito’s Libro da la Ventura was a source of inspiration for numerous later compilations, in print as well as in manuscript. Manuscript versions—all of the greatest rarity, owing to the fragility of supports and their extensive use at social occasions—present particularly exciting case studies as the “game” could be modified to reflect the owner’s personal associations with fate and chance. Below we present two examples of such manuscript versions, each demonstrating a close allegiance to Spirito’s foundational work as well as precious innovations that makes these “new” works entirely unique.

The Renaissance fortune-telling book goes Baroque

The first example is a very refined seventeenth-century manuscript containing Spirito’s Libro della Ventura and profusely embellished with high-quality ink drawings that beautifully exemplify the organic ornamentality of the Baroque.

The manuscript text is copied from Spirito’s printed edition nearly verbatim, as are the major figures and motifs (kings and wheels of fortune, for example) thus allowing for standard game play. This is consistent with the majority of printed editions of Spirito, too. “Italian [editions] reflect either the continued use of the same woodblocks, or use illustrations based on earlier cuts; at the same time the arrangement of the text and woodcut material is limited or re-created… [T]he same is true for the translations of Il libro into other European vernaculars, especially French: although subsequent editions differ from each other, they all feature the layout of earlier volumes, as a consequence echoing incunabula copies of Spirito’s work.” (J. Kiliańczyk-Zięba, “In Search of Lost Fortuna: Reconstructing the Publishing History of the Polish Book of Fortune-Telling,” p. 133).

[After Stefano della Bella]. Lorenzo Spirito, Libro della Ventura. Manuscript drawn and calligraphed in brown ink, in Italian. Italy (possibly Florence?) ca. 1650.

See the full description of this copy here.

In terms of illustrations, the manuscript includes ten full-page drawings of busts of kings placed upon pedestals and within decorative rectangular frames, and twenty full-page tables of dice, each bearing at the centre a small drawing of the various figures presented in the game (real or imaginary animals, zodiac signs, emblems, etc.). There are also twenty full-page drawings of wheels of fortune, again with each figure placed at the centre, set before largely pastoral landscapes. Under each wheel is a vignette with scenes of travellers, putti, castles, etc. These are followed by twenty double-page spreads dedicated to the prophets, featuring their respective portraits on the first page set within a garland, extensive calligraphic text in terzine that carries through both pages, and finally a highly inventive 'carpet' drawing at the bottom of the second page.

The precise edition source of Spirito's text remains unknown. Comparison with the printed editions nonetheless suggests the basic trajectory: schematic woodcut figures (with frequent re-uses of the same block) are replaced by the individuation of figures, often with orientalizing, 'a l'antica', or historicizing detail, and by fine modeling and minute cross-hatching. Artistically, the 'carpet' drawings, which occupy a quarter to half of the lower margin, are among the most inventive in the album. Subjects include capricci, pastoral scenes of animals, seascapes, landscapes, fortified cities, and putti at play. A few are emblematic: one in which three putti seem to be playing a game involving a certain number of coins hidden under a hat (fol. 29r), with one of the three (the loser?) in tears; or another in which a small putto appears to be suckling an antlered deer (fol. 32r).

The illustrations in this manuscript are also far more embellished than those of earlier editions, and executed in the manner of the prominent Italian draughtsman and printmaker Stefano della Bella (1610-1664). A prolific artist, della Bella was particularly well known for the vastness of his subject matter which ranged from wittily inventive ornamental plates, frontispieces, and capricci to illustrations for theatre productions, scenes of the military arts and the royal court, and even metaphorical representations of skeletons during the plague. So varied was della Bella's work that he was even commissioned to produce four sets of educational playing cards for the young Louis XIV covering history, mythology, and geography.

The artist’s style is felt throughout the manuscript; thematically, for example, in the small, elaborately costumed figures in fancy headdresses that recall his interest in Rembrandt, or in the array of animals that enliven the page as they scamper across imaginative landscapes (in fact, della Bella was undertaking a series of etched animal portraits right around the date we propose the manuscript was produced, and certain animals, such as the deer and eagles, demonstrate remarkable similarity to those included in his series). Formally, the remarkable sense of luminosity and texture evident in the hair, feathers, grass, leaves, and sky – achieved through sure, painterly yet delicate strokes economically and efficiently employed to let the white ground come through – is practically signature della Bella. A further point to the level of creativity demonstrated in this manuscript: the 'carpet' drawings mentioned above bear no evident relation to the illustrations in any printed edition of the book.

The visual coherency of this manuscript is further strengthened by the unity of 'disegno' between the drawings and the three columns of calligraphic text, such that one may infer that artist(s) and calligrapher worked in close collaboration. This is nowhere more evident than in the magnificent title leaf or the drawing on the following verso. The opening leaf gives the title in Roman capitals, beneath which are some introductory verses, not present in the received text. The text proper begins on the verso of the same leaf ('Qui comincia il libro'), and is neatly presented on a large curtain, a common trope of the Baroque, held at the top by three putti.

The manuscript’s opening leaf, with the title in Roman capitals, beneath which are some introductory verses which are not present in the received text.

We suggest the motive for the present manuscript was the production of a luxury object, probably for presentation, rather than simply a 'copy' of an increasingly rare printed text. The carefully cut tabs in the right margins make it clear that it was to be played as a game, and minor defects suggest other signs of use. The drawings were clearly made on individual sheets and then bound; although the paper stock is uniform, the sizes of the individual leaves are not, hence some irregularity in the fore-edges, a few of which are gauffered.

The manuscript ends with what, in retrospect, seems a joke: a later hand has written in a colophon imitating that of a printed book and stating that the text was written and personally copied by Lorenzo Spirito and illustrated by his countryman Paolo Veronese (1528-1588), followed by a date which is sheer nonsense.

Poetry, Fortune, And Gambling: The Spello-Game

Another unrecorded and extremely interesting variant on Spirito’s Libro della Ventura is in the form of a manuscript likely produced in Spello around the end of the seventeenth century.

This fortune-telling book involves a more personal adaption of the structure and rules of the game as developed by Spirito. Here the reader-player wanders not among celestial spheres, prophets, kings, and philosophers, but instead moves through the history and cultural tradition of Spello, the ancient Roman town known as Hispellum and located in east central Umbria. Evidently, the anonymous author who produced this Vago, e diletteuole giuoco della diuitia di Spello (according to the title inscribed on the verso of the second leaf) sought to celebrate the city’s ancient monuments, as well as the numerous poets born there over the centuries, including the illustrious Propertius.

[Spello?]. Vago e diletteuole giuoco della diuitia di Spello. Illustrated manuscript on paper, in Italian. Spello (?), end of the seventeenth century-beginning of the eighteenth century.

See the full description of this manuscript here.

The rules of the game are explained in the preliminary pages. As with the “regular” Spirito version, players were to choose one of the questions listed ('Partiti da Proponersi dal Signore') pertaining to health, wealth, career, business, travel, and happiness in love and marriage. They then threw two dice and proceeded to locate the cast result in the following twelve tables of diagrams, each of which bears, at the centre, a drawn vignette with views or monuments of Spello. The diagrams guided players to twelve sections of quatrains which provided answers to the chosen questions, each introduced by a full-page drawing depicting a poet born in Spello.

The final drawings depict poets who were active in the 1600s, a feature that allows us to date the execution of the present manuscript to the end of the seventeenth century. In particular, the drawing on the recto of fol. 31 depicts the poet and musician Giovanni Francesco Marcorelli (d. ca. 1656), an organist at the Collegiata Santa Maria at Spello between 1627 and 1634 who was then active as maestro di cappella in the oratory of the Church of Santa Maria Nova in Rome. Marcorelli also composed some oratories and in the present manuscript is shown writing a musical score.

Remarkably, the Spello-game also doubles as a gambling game as it involves a stake with pecuniary value (referred to as Tesoro in the preliminary instructions, and managed by a Tesoriere, or banker): in the quatrains the prediction of future events is therefore supplemented, in the final verse, with the notice of an amount to be payed or cashed out. Evidently the fortune-telling book had begun to enter a new phase of fortunes.

References

Sander 7047; A. de Vesme - P. D. Massar, Stefano della Bella. Catalogue raisonné, Milano 1906 (New York 1971); T. De Marinis, “Le illustrazioni per il Libro de le Sorte di Lorenzo Spirito”, Idem, Appunti e ricerche bibliografiche, Milano 1940, pp. 67-83; A. Blunt, The Drawings of G.B. Castiglione and Stefano della Bella in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, London 1954; P. D. Massar, Presenting Stefano della Bella, Seventeenth-Century Printmaker, Greenwich, CT 1971; L. Hartmann, “Capriccio”. Bild und Begriff, Nürnberg 1973; C. Limentani Virdis, Disegni di Stefano della Bella, Sassari 1975; M. Catelli Isola (ed.), Disegni di Stefano della Bella 1610-1664. Dalle collezioni del Gabinetto Nazionale delle Stampe, Roma, Villa della Farnesina alla Lungara, 4 febbraio – 30 aprile 1976 (exhibition catalogue), Roma 1976; Le carte da gioco di Stefano della Bella (1610-1664), Firenze 1977; M. Sensi – L. Sensi, “Fragmenta hispellatis historiae. 1. Istoria della terra di Spello, di Fausto Gentile Donnola”, Bollettino storico della città di Foligno, 8 (1984), pp. 7-136; A. Tini Brunozzi, “Appunti sulla toponomastica spellana”, ibid, 19 (1995), pp. 299-329; T. Ortolani (ed.), Stefano della Bella. Aggiornamento al “Catalogue raisonné” di A. de Vesme e Ph. D. Massar, 1996; L. Nadin, Carte da gioco e letteratura fra Quattro e Ottocento, Lucca 1997; L. Nadin, Carte da gioco e letteratura fra Quattro e Ottocento, Lucca 1997; S. Urbini, Il Libro delle sorti di Lorenzo Spirito Gualtieri, Modena 2006; S. Karr Schmidt, "Art—A User’s Guide: Interactive and Sculptural Printmaking in the Renaissance." Ph.D., New Haven 2006; D. Klemm, Stefano della Bella (1610-1664). Zeichnungen aus dem Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle, Köln-Weimar-Wien 2009; G. Proietti Bocchino, Spello città d'arte, Perugia 201; A. Rosenstock, Das Losbuch des Lorenzo Spirito von 1482: eine Spurensuche, Weißenhorn 2010; J. Kelly, “Renaissance Futures: Chance, Prediction, and Play in Northern European Visual Culture, c. 1480-1550,” Ph.D., Berkeley 2011; D. Klemm (ed.), Von der Schönheit der Linie. Stefano della Bella als Zeichner. Hamburger Kunsthalle 25. Oktober 2013 bis 26. Januar 2014, Petersberg 2013; A. L. Palmer, “Lorenzo ‘Spirito’ Gualtieri’s Libro delle Sorti,” Sixteenth Century Journal XLVII/3 (2016), pp. 557-578; J. Kelly, “Predictive Play: Wheels of Fortune in the Early Modern Lottery Book,” A. Levy (ed), Playthings in Early Modernity: Party Games, Word Games, Mind Games, Kalamazoo 2017, pp. 145-166; J. Kiliańczyk-Zięba, “In Search of Lost Fortuna: Reconstructing the Publishing History of the Polish Book of Fortune-Telling,” F. Bruni-A. Pettegree (eds), Lost Books: Reconstructing the Print World of Pre-Industrial Europe, Leiden 2017, pp. 120-143; Philobiblon, One Thousand Years of Bibliophily, nos. 42, 202, and 220.

How to cite this information

Julia Stimac and Margherita Palumbo, “On Fortune-Telling Books: A Spirito Incunable and Two Later Manuscripts” PRPH Books, 29 April 2020, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/fortune-telling-books. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

![The first printed fortune-telling book: Lorenzo Spirito’s Libro da la Ventura [Bologna, Caligola de Bazaleriis, 1498-1500].See the full description of this copy here.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1588172411992-0MAWTJIKXH5WXZUK6Z6A/Spirito+1498+wheel.jpg)

![Title page of Lorenzo Spirito’s Libro da la Ventura [Bologna, Caligola de Bazaleriis, 1498-1500].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1588172401364-QHHH3DUJZ8Z76ZI4MUHJ/Spirito+1498+title.jpg)

![[After Stefano della Bella]. Lorenzo Spirito, Libro della Ventura. Manuscript drawn and calligraphed in brown ink, in Italian. Italy (possibly Florence?) ca. 1650.See the full description of this copy here.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1588172424974-GMB5U6D6MQQ4VJ0L3E6E/Spirito+manuscript+1.jpg)

![[Spello?]. Vago e diletteuole giuoco della diuitia di Spello. Illustrated manuscript on paper, in Italian. Spello (?), end of the seventeenth century-beginning of the eighteenth century.See the full description of this manuscript here.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1588194013065-3XR5JOS78RHXO4VRSCAY/Spello+1.jpg)