Forty years later… stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus

Already 40 years has passed since the publication of Umberto Eco’s first novel, the world-wide bestseller Il nome della rosa (The Name of the Rose). From its first appearance, it was a great success, winning the 1981 Strega Prize, the most prestigious Italian literary award, and the 1982 Prix Medicis Étranger, a renown French literary prize awarded to an author whose “fame does not yet match their talent.” The latter description would not fit Eco long: The Name of the Rose garnered the semiotician a vast literary and academic following, broadened still in 1986, when a film adaptation was released, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud and starring Sean Connery and Christian Slater.

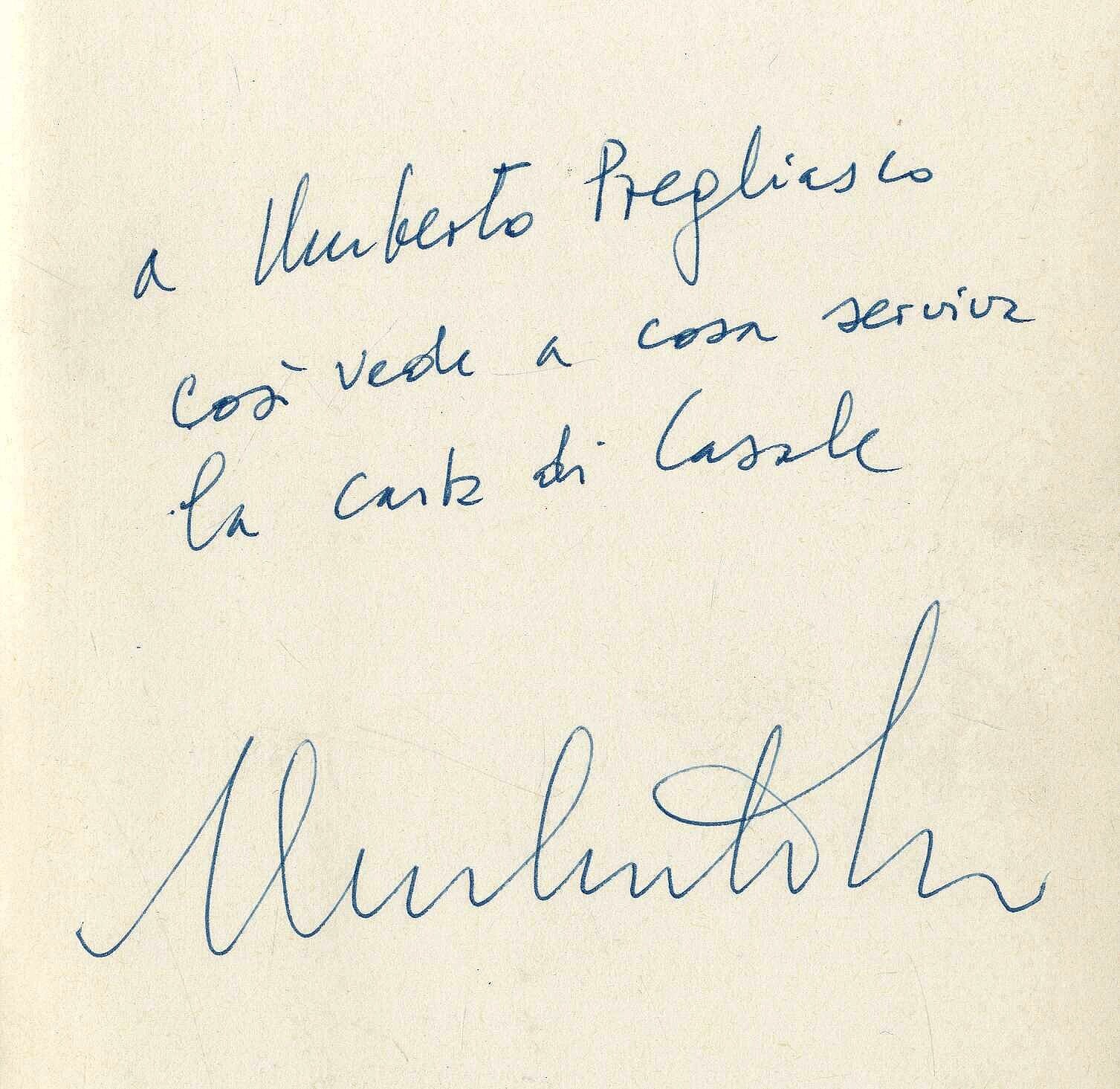

A first edition copy (not for sale) of Eco’s masterpiece, dedicated to my father Arturo Pregliasco.

Umberto Eco (1932-2016). Il nome della rosa. Milano, Bompiani, 1980.

The text is set up as a book within a book: it opens with a prologue by an unknown narrator who explains his discovery of a manuscript written by a 14th-century German monk named Adso of Melk. The narrator expresses his hesitation in believing the authenticity of the text, as both artefact and narrative, but explains that he nevertheless decided to translate and publish it so the incredible story could be shared. A second prologue follows, that of the manuscript itself, written by Adso at the end of his life. Here Adso introduces the reader to the fascinating tale of a week-long episode from his youth as a Benectine novice when, in 1327, he and an older Franciscan friar named William of Baskerville were engaged in solving a string of mysterious deaths in a north Italian monastery. From here, the plot develops around a missing manuscript, the second volume of Aristotle’s Poetics on comedy, and a hidden, forbidden room in the abbey’s labyrinthine library called the finis Africae.

But just as The Name of the Rose presents a book within a book, it also offers another kind of book alongside that of the novel. That is, the book is arguably most remarkable for its simultaneous defense of semiotics, as it cogently develops theological, philosophical, and historical investigations into the nature of “truth.” For example, the “detectives” are keen to follow the “signs” they come across and believe in the ability to “read” nature. Likewise, the reader becomes sure there is a pattern to the deaths, which must all be murders. But nothing is so clear in the end as not all deaths are murders and questions remain unanswered. Even the title of the book plays with the unknown, invoking the ubiquitous symbol which avoids conferring any single meaning.

The text is rich with references to other literary works and figures, as with the character of Jorge of Burgos, a tribute to the writer Jorge Luis Borges, who had a profound impact on Eco’s work, and makes significant use of anachronistic pastiche. In these ways and many others, the work is wonderfully inter-textual and becomes a metatextual statement about the way texts work together in the creation of meaning. This was key to Eco as writer, as well as Eco the bibliophile.

I had the privilege of meeting Eco while he was writing this masterpiece. He would often visit our bookshop in Turin, just as he did back in the 1950s when, as a penniless student, he would timidly look for second-hand books in my grandfather's bookstore by the University College of Turin, where Eco graduated with a thesis on the aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas.

As evinced by his great erudition and “metatextual” writing, Eco was indeed a great lover of books. Over the years, I often wondered which came first in his novels, the chicken or the egg: by this I mean I have always tried to understand whether it was the writer’s need that guided his book collecting, or if it was the possession of certain books that would inspire his writing.

Certainly his curiousity about truth and thought was a great motivation. He used to say: “I am fascinated by the human propensity for deviating thought. So I collect books about subjects in which I don’t believe, like kabbalah, alchemy, magic, invented languages. I am interested in fakes, in falsity. I don’t have Galileo, but I have Ptolemy, because he was wrong”.

When, after his death, I had the opportunity to visit his library on my own for the first time, I came close to solving the puzzle: within the expansive collection of volumes, I finally noticed that the books were already gathered “by novel”. Some two separate shelves included texts about alchemy, Rosicrucianism, and the Knights Templar, the esoteric sources behind Foucault's Pendulum (1988). I likewise discovered three shelves reserved for The Island of the Day Before (1994): books about the Jesuit order, navigation and astronomy. I could find Crusades, Niketas Coniate and Barbarossa in the Baudolino (2000) department, while the pamphlets dealing with conspiracies, forgeries, and anti-Semitism were in the shelves he kept for The Prague Cemetery (2011).

Just as striking, however, was the relative dearth of books related to his most "medieval" novel: the documentation for The Name of the Rose in terms of the herbaria, the texts on drugs, the labyrinths and the Inquisition was instead carried out through reference to modern texts. Indeed, the possibility of starting a serious collection of books only came about after the great sales, over the years, of his first masterpiece (which now counts among the select number of books to have sold over 50 millions copies worldwide).

It was then that I could finally appreciate what Eco told me many years ago: "My collecting was born around eight years old, from having discovered in the cellar unbound books, which belonged to my grandfather. The collection of old books instead began when I wrote The Name of the Rose. Since I made money with a book, I spent the money on other books”. Unfortunately, a manuscript of the lost second book of Aristotle’s Poetics, the one about laughing which engenders Jorge’s homicides and the fire in the labyrinthine library (surely the source of the worst nightmares for any antiquarian bookseller!) was nowhere to be found.

— Umberto Pregliasco

Watch the remarks given by Umberto Eco, Arturo Pregliasco, Vincent Buonanno and Filippo Rotundo at the opening of PRPH Books in 2013.

How to cite this information

Umberto Pregliasco, 'Forty years later… stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus," 19 February 2020, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/eco-anniversary. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.