Adventures in Courtly Love

With Valentine’s Day right around the corner, we’re highlighting some important literary contributions to the notion of love, especially of the nobly inspired courtly conception that lies at the heart of a great many love stories.

In the 14th century, Valentine’s Day – first officially recognized by Pope Gelasius I in 496 AD — acquired a romantic dimension. The development is reflected in one of the first literary references of the day as a day of romance, in Chaucer’s 699-poem, The Parlement of Foules. Likely composed around 1381-1382, and possibly to honour the anniversary of his patron King Richard II’s engagement to Anne of Bohemia, the poem speaks of a parliament of birds congregating on Saint Valentine’s Day to choose their mates: “For this was on seynt Volantynys day / Whan euery bryd comyth there to chese his make.”

Chaucer’s poem opens with the narrator reading Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis before drifting off to sleep. Scipio Africanus proceeds to lead him through a dream-vision and together they travel across celestial spheres, through a daunting gate and the dark temple of Venus, and emerge into brightness where the goddess Nature has gathered a parliament of birds. Of great variety, the birds engage in a lively debate on the nature of love while Nature herself lets them pair off or stay single, as they please.

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). La Divina Commedia di Dante Alighieri Con varie Annotazioni, e copiosi Rami adornata... Tomo Primo [- Terzo]. Venice, Antonio Zatta, 1757. [Together with:] Idem. Prose, erime liriche edite, ed inedite di Dante Alighieri, con copiose ed erudite aggiunte... Tomo Quarto Parte Prima [-Seconda]. Venice, Antonio Zatta, 1758.

It is not surprising that one of Chaucer’s main sources was Dante’s Commedia, an influence that becomes particularly clear in the Parlement’s references to the Purgatorio and early cantos of the Inferno. In addition to Dante being one of the “three crowns” of Italian literature (along with Boccaccio and Petrarch), love is a strong theme in the Comedy, and while it is Virgil that guides Dante through Hell and Purgatory, it is Beatrice, Dante’s own great love and muse, who guides him in Paradise.

The famous love story of Dante and Beatrice is described in his Vita Nuova of 1294, which was included in the celebrated collection of Tuscan poets published by Giunta under the title Sonetti e’ Canzoni in 1527. Dante and Beatrice first met as children when she was eight and he was nine. He immediately fell in love with her, even though, despite their youth, they were already betrothed to their future spouses. Nine years after the initial meeting, they met again in the streets of Florence and she spoke to him. He rushed home to dream about her and began composing La Vita Nuova. They never spoke again after that meeting, but he would continue always to love and idealize her.

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). Sonetti e’ Canzoni di diuersi antichi Autori Toscani in dieci libri raccolte. Di Dante Alaghieri Libri quattro. Di M. Cino da Pistoia Libro uno. Di Guido Cavalcanti Libro uno. Di Dante da Maiano Libro uno. Di Fra Guittone d’Arezzo Libro uno. Di diuerse Canzoni e’ Sonetti senza nome d’autore Libro uno. Florence, Filippo Giunta's heirs, 6 July 1527.

Read the full description of this copy here.

Love and idealization are inextricably linked in the sort of medieval courtly love typified by Dante and Beatrice. Whereas marriage among nobility was generally based on wealth and family history, courtly love — which developed as a literary genre in France at the end of the eleventh century — provided a romantic alternative, one focused on personal character, with valour and impressive deeds being particularly prized along with kindness and devotion. It also rebelled somewhat against the status of women as property (first of their fathers and then of their husbands) by upholding them as an ideal. As such, this type of love, though based on sexual attraction and a glorification of amorous passion, was more spiritual or psychological than anything: it was considered ennobling, as with Dante’s binding, unfulfilled lifelong love and continued presentation of Beatrice as female perfection and a source of inspiration.

Gallant knights performing courageous deeds to become worthy of unattainable ladies epitomized the sort of subservience of men to (idealized versions of) women so characteristic of this type of love, and such tales circulated widely in courtly circles.

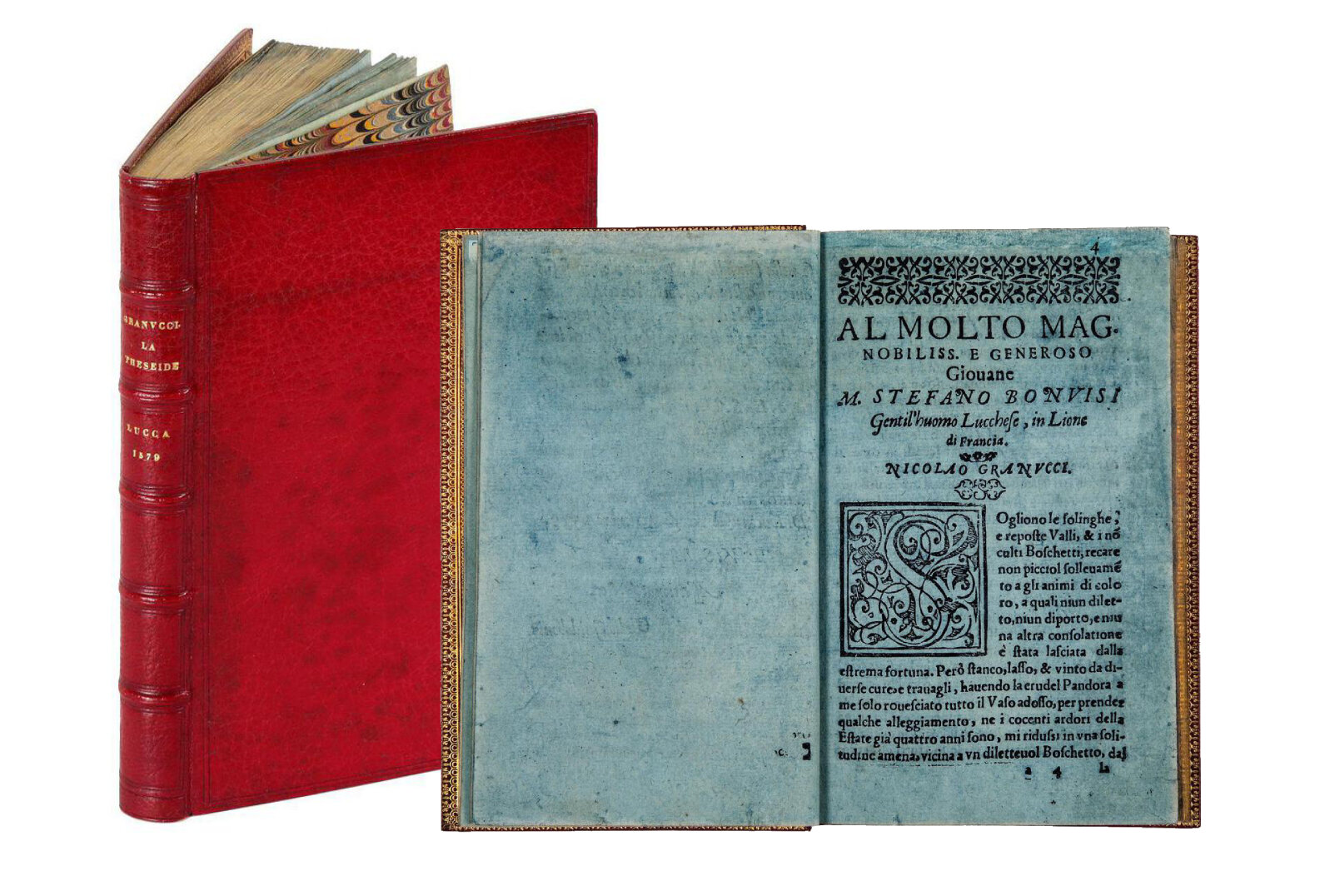

Boccaccio brought new significance to the coupling of chivalry and romance when he elided ancient warriors and gallant knights in his Teseida. Composed between 1339 and 1341 and divided into 12 books (based on the model of Vergil’s Aeneid), the Teseida is an epic poem that combines elements from the classical epics and the contemporary tradition of love literature. Its stated subject is the story of the ancient Greek hero Theseus, but it is primarily devoted to relaying what becomes a great and perilous rivalry between two royal Theban cousins Palemone and Arcita for the love of the beautiful Emilia. Arcita is finally deemed victorious in the pursuit by proving his ultimate knightly prowess in a dangerous tournament, but is badly wounded in doing so. On his deathbed, Arcita unselfishly surrenders his beloved to his rival, demonstrating anew the dignifying activity of courtly love.

Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375). La Theseide... Innamoramento piaceuole, & honesto di due Giouani Thebani Arcita & Palemone; D’ottaua Rima nuouamente ridotta In Prosa per Nicolao Granucci di Lucca. Aggiuntoui un breve Dialogo nel principio e fine dell’Opera diliteuole, & vario. Lucca, Vincenzo Busdraghi for Giulio Guidoboni, 1579.

Read the full description of this copy here.

The Teseida’s almost 10,000 lines were widely influential. In addition to establishing the traditional form of ottava rima for epic verse, it was highly instrumental in popularizing the connection between arms and love, providing the inspiration for Chaucer’s A Knight’s Tale and indeed fueling the long line of chivalric romances to come.

An important text in this lineage is Matteo Maria Boiardo’s unfinished Orlando Innamorato (Orlando in Love), published between 1483 and 1495, which follows the adventures of Rinaldo da Montalbano and his cousin, the heroic knight Orlando, along with their love and loyalty for the beautiful Angelica.

Matteo Maria Boiardo (ca. 1441-1494). Orlando innamorato. I tre libri dello innamoramento di Orlando... Tratti dal suo fedelissimo essemplare. Nuovamente con somma diligenza revisti, e castigati. Con molte stanze aggiunte del proprio auttore, quali gli mancavano. Insieme con gli altri tre Libri compidi. Venice, Pietro Nicolini da Sabbio, March-April 1539.

Read the full description of this copy here.

In the complete Orlando Innamorato printed by Nicolini da Sabbio in 1539, the three books originally written by Boiardo are continued and completed by three other books composed by Nicolò Degli Agostini (fl. first quarter of the sixteenth century). These supplementary books were published together with the three books by Boiardo up to the end of the seventeenth century.

Another continuation of Boiardo’s unfinished romance was provided by Ludovico Ariosto with his Orlando Furioso in 1516. A landmark of this important work was when Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari printed his first Furioso in 1542, a publication which goes far beyond previous editions by other printers: for the first time the text of the poem is supplemented with commentary, and each canto is introduced by a woodcut vignette, as well as an argomento. The success of this innovative publication was immediate and unprecedented, and the Furioso became the 'symbol' of the printing house itself. From 1542 onwards the poem was constantly re-issued, both in quarto and, as of 1543, in the cheaper and more popular octavo format, thus transforming the Furioso into a 'classic' of modern literature and firmly tying Ariosto’s name to the chivalric tradition.

Ludovico Ariosto (1474-1533). Orlando furioso... nouißimamente alla sua integrita ridotto & ornato di varie figure. Con alcune stanze del S. Aluigi Gonzaga in lode del medesimo. Aggiuntoui per ciascun Canto alcune allegorie, & nel fine una breue espositione et tauola di tutto quello che nell’opera si contiene... Venice, Gabriele Giolito de’ Ferrari, 1546. [together with:]

Dolce, Lodovico (1508-1568). L’Espositione di tutti i vocaboli, et luoghi difficili, che nel Libro si trouano; Con una brieue Dimostratione di molte comparationi & sentenze dell’Ariosto in diuersi auttori imitate. Raccolte da M. Lodouico Dolce.... Venice, Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari, 1547.

Read the full description of this copy here.

With the rise of individualism promoted through the Renaissance, courtly love as an alternative to marriage waned, and romantic love as the basis for marriage became increasingly conceivable. Nevertheless, certain tropes of courtly love, like the combination of passion and unattainability, were here to stay.

Such a transitional moment in the concept of courtly love is considered in an important novella by Masuccio Salernitano (born Tommaso Guardati; 1410–1475), specifically the 33rd novella of a collection of 50 included in his Novellino, composed between 1458 and 1475 and first published in Naples in 1476. Written in Italian vernacular, the tragic tale narrates, as the author writes in the dedication, “the most pitiful, unfortunate case” of two young, star-crossed lovers Mariotto Mignanelli and Ganozza (or Giannozza) Saraceni, who hail from warring Sienese families. Many plot points will be familiar: the pair secretly get married, Mariotto is exiled after he is found guilty of murder, Ganozza is promised in an arranged marriage and fakes her death, and fatally timed messaging leads to both lovers’ tragic ends. The story was transplanted to Verona and revisited by Luigi da Porto (1485-1529) as Giulietta e Romeo and by Matteo Bandello (1485-1561) as Giuletta e Romeo, before being taken up by Shakespeare in Romeo and Juliet.

Masuccio Salernitano (1410-1475). Nouella di Marioto Senese. [Italy, 1530s?].

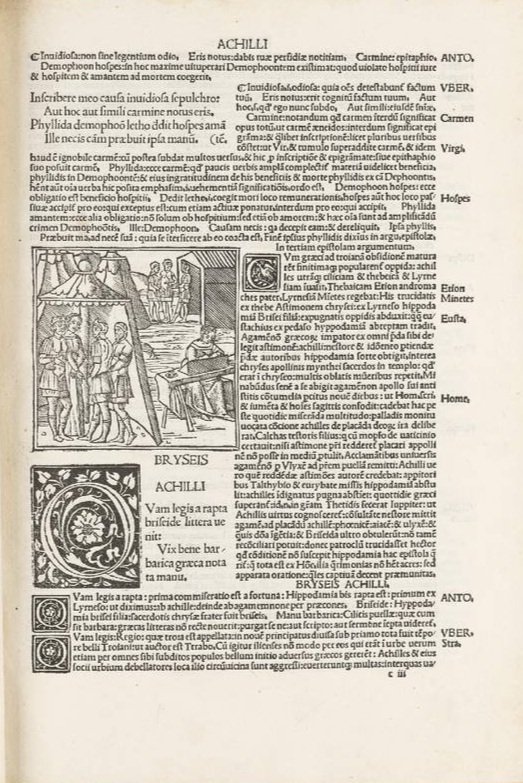

The early roots of the literary genre of courtly love are contested, but Ovid's Ars amatoria of 2 AD is often considered an important source. Interestingly, around the same time the Roman poet was writing that instructional set of elegies, he also composed his Epistolae Heroides (Letters of Heroines), a collection of imagined letters giving voice to legendary women who were abandoned or otherwise mistreated by their lovers or husbands. Counting among Ovid’s heroines are Penelope, Phaedra, Dido, Deianira, Ariadne, Medea, Helen, Hero, and Sappho. The fictional epistolary frame is further ensured by the presence of six double-letters, wherein the recipient responds to the original sender. These occur between Paris and Helen, Leander and Hero, and Acontius and Cydippe. Particularly remarkable is the way the poet represents his figures with psychological complexity and realistic personalities, humanizing the mythical heroines to understand their lived experiences.

Ovidius Naso, Publius (43 BCE-17/18 CE). Epistole Heroides Ouidii cum com[m]netariis Antonii Volsci Et Ubertini Clerici Crescentinatis. Cum gratia et privilegio. Venice, Bartolomeo Zani, 20 December 1507.

Read the full description of this copy in our forthcoming Italian Books III.

The epistolary frame was particularly well supported by sixteenth-century illustrated editions of the Heroides. While incunable editions limited the illustration to a single woodcut portraying an author among his commentators or disciples, a new template was introduced by the Venetian Johannes Tacuino in the Heroides of 1501, which opened each letter with a vignette depicting salient episodes in the story. Bartolomeo Zani elaborated and refined this approach with the illustrations for his 1506 edition of the Heroides, which was perfected in the 1507 edition with the introduction of a final woodcut for the story of Sappho and Phaon, previously missing.

A complete description of our currently available copy of the rare 1507 edition is forthcoming in our upcoming catalogue, Italian Books III, but it is enough to note here that both the Tacuino and the Zani sets mainly depict the heroines at their desks and in the act of writing, a template later employed in manuscripts addressed to women, or in editions of works composed by female authors. With such portrayals heightening the heroines’ psychological depths, the legacy of Ovid’s Heroides presents a fine contrast to the sort of passive, idealized women that predominate in the literature of courtly love, a reminder of the complex entanglement of gender, sex, and society that always continues to shape cultural notions, and descriptions, of love.

How to cite this information

Julia Stimac, "Adventures in Courtly Love," 9 February 2022, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/courtlylove. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.