A gift from Peiresc to his friend Gassendi

We are pleased to present an extraordinary association copy: the second Latin edition of De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum, Libri IX by the English philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon (1561-1626), comprising his famous manifesto on the scientific method and advancement of knowledge. This work represents Bacon’s signal effort: no less than a “total reconstruction of sciences, arts and all human knowledge, raised upon the proper foundation” (Prooemium of the Instauratio Magna), and this particular volume’s extraordinary provenance — gifted by Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc to Pierre Gassendi — is a testament to the power such an effort was to achieve in the “modern” world.

De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum outlines a classification of human knowledge in terms of three categories—History, Poesy, and Philosophy—these relating to the three fundamental “faculties” of the mind—memory, imagination, and reason. Working within this taxonomy, Bacon elaborated a scientific method based on inductive empirical experimentation and the accumulation of data collected through the observation of nature (reason), in contrast to the former practice of acquiring knowledge through the received wisdom of ancient texts (these being largely the province of memory and myths, i.e. imagination).

The uneasy position of astrology relative to science provides a fine example of the significance of Bacon’s position. The philosopher still regarded astrology as an important complement to the study of astronomy (which Bacon classified under physics, rather than the “mathematical arts”), where the former is described as knowledge of the significance of celestial movements and the latter as knowledge of the movements themselves (B. Dooley, “Astrology and Science”, A Companion to Astrology in the Renaissance, Leiden-Boston 2014, p. 239). However, he felt that astrology was “so full of superstition, that scarce anything sound can be discovered in it” (Book II, Chapter 4). Instead, he sought a “purification” of the practice with a “just astrology” based on “the real effects of the celestial bodies upon the terrestrial” (Book IX).

Bacon thus proposed an entirely radical idea: “a collaborative effort of hitherto unimagined proportions, to proceed from the mass of evidence to the formulation of new laws” (Dooley, p. 240). This was the basis for what he termed the “New Science”.

This finely bound volume belonged to one of the key players in the dissemination of Bacon’s work, the renowned savant, naturalist, antiquarian, collector of books, and great patron – as well as amateur practitioner – of science and art, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580-1637). Further, Peiresc presented the book as a gift to his dear friend and intellectual interlocutor Pierre Gassendi (1592-1655), the famous philosopher and astronomer who was also among the earliest French admirers of Bacon’s experimental philosophy. The present volume thus represents an extraordinary union of three of the principal advocates of the New Science: Bacon, Gassendi, and Peiresc.

Portrait of Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc. Engraving by Claude Mellan, 1637.

Nicolas-Claude Fabri, seigneur de Peiresc was born in Belgentier or Beaugensiers, to the north of Toulon, in Provence in 1580. He was educated at the Jesuit College de Tournon in Avignon, where he studied not only humanistic disciplines, abut also astronomy. Between 1599 and 1601, he travelled throughout Italy, visiting academies, libraries and cabinets, and making the acquaintances of several scientists and other learned men. He enrolled at the University of Padua, where he met Galileo Galilei (1564-1642). In subsequent years he took an active interest in the telescopic discoveries of the Florentine scientist, as well as in his inquisitorial sufferings; taking up his cause, Peiresc tried in vain to help Galileo by enlisting the aid of the pope’s nephew and Vatican secretary of state, Cardinal Francesco Barberini. Peiresc had a close relationship with the cardinal, who stayed at the Frenchman’s home on his way back from a special diplomatic mission in Paris in 1625, a year after the present volume was published.

Galileo Galilei, Il Saggiatore nel quale con bilancia esquisita e giusta si ponderano le cose contenute nella Libra astronomica e filosofica di Lotario Sarsi Sigensano... Rome, Giacomo Mascardi, 1623.

Title-page portrait of Galileo within a fine engraved architectural border by Francesco Villamena (ca. 1566-1626).

This is one of only a few copies printed on thick paper, bound for the Barberini Family. See the complete description here.

Peiresc’s deep esteem for Galileo is clearly demonstrated in the first letter he wrote directly to the scientist in January 1634, after the latter’s forced abjuration in 1633 and the prohibition of his celebrated Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del Mondo. In the letter, Peiresc vividly recalls their encounter in Padua thirty-five years ago, and he tells Galileo of his impassioned reading of the Sidereus Nuncius, which had affected him so greatly that, immediately following its publication in 1610, he had had an observatory built in his Hôtel de Callas in Aix-en-Provence.

From 1610 onwards, Peiresc proceeded to spend years not only collecting books and antiquities, but also recording the times of planetary events and calculating terrestrial longitudes. He is generally credited with the identification – in precisely 1610 – of the Great Nebula in the constellation Orion. Together with his friend Pierre Gassendi – the future recipient of the present copy of De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum – he observed the lunar eclipse of 20 January 1628 and commissioned the first mapping of the moon, engaging the renowned French engraver and Peiresc’s protégée Claude Mellan (1598-1688) to produce images of various lunar phases observed in Aix in 1635.

In this sense, both Gassendi and Peiresc are Baconian. Bacon argues that true knowledge could be obtained only through the study of nature and its phenomena, and recommends an exhaustive collection of observations as the basis for drawing conclusions.

Portrait of Francis Bacon, Viscount St Albans. Line engraving by J. Houbraken, 1738.

“He admired the Genius, and approved the design of the great Chancellour of England Sir Francis Bacon, often grieving that he never had the happinesse to speak with him.”

That Peiresc greatly admired the English philosopher is attested by Gassendi himself in the latter’s biography of his friend, first published in Latin in 1641 (Viri illustris Nicolai Claudii Fabricii de Peiresc Senatoris Aquisextiensis Vita) and translated into English in 1657:

No man made more observation, or procured more to be made, to the end that at last some Notions of natural things more sound and pure, than the vulgarly received, might be collected: for which cause he admired the Genius, and approved the design of the great Chancellour of England Sir Francis Bacon, often grieving that he never had the happinesse to speak with him.

(P. Gassendi, The Mirrour of True Nobility and Gentility Being the Life of the Renowned Nicolaus Claudius Fabricius, Lord of Pieresk, London 1657, p. 207).

Peiresc developed a large network of scientific correspondents, contacted learned people throughout Europe, shared information, and sponsored research and, significantly, book publications. In fact, he was directly involved in the publication of the 1624 edition of the De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum, which first appeared in 1623 in London as an expanded version of the earlier On the Proficience and Advancement of Learning (1605). In November 1623 Peiresc had received a letter from the Italian scholar and antiquarian Cassiano del Pozzo containing a notice of the publication, in London, of the De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum. In Peiresc’s opinion, the circumstances were also favorable for proposing that an edition of this work be printed in France, juxta exemplar Londini. Unlike the London folio edition, however, a quarto format was chosen for the volume, which was printed by the Pierre Mettayer, this latter having been active in Paris as typographus regius, i.e. royal printer since 1596.

Bacon, Francis (1561-1626). De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum, Libri ix. Ad Regem suum. Iuxta Exemplar Londini Impressum. Paris, Pierre Mettayer, 1624.

See the complete description of this extraordinary association copy here.

Peiresc was one of the greatest intermediaries in the Republic of Letters, and had copies of ‘his’ De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum sent to his correspondents – including Cardinals Francesco Barberini and Scipione Corbelluzzi in Rome – hot off the press, thus securing for himself a pivotal role in the dissemination of Baconian thought across continental Europe.

At the beginning of March 1636, Pierre Gassendi arrived at Peiresc’s residence; he would be a frequent visitor there until the latter’s death in 1637. This date is known through the famous letter Gassendi wrote to Galileo’s well-known friend, the Genevan Elie Diodati (1576-1658), which was sent from Aix-en-Provence and dated 8 April 1636. In the letter, Gassendi collates for his correspondent the reports on the Lunar eclipse of 28 August 1635, which, thanks to Peiresc’s vast network of contacts, had been sent back not only from Aix, Digne, and Paris, but also from Rome, Naples, Cairo, Aleppo, Tunis, and even far away Québec.

Portrait of Pierre Gassendi. Engraving by Claude Mellan, ca. 1637 or 1638

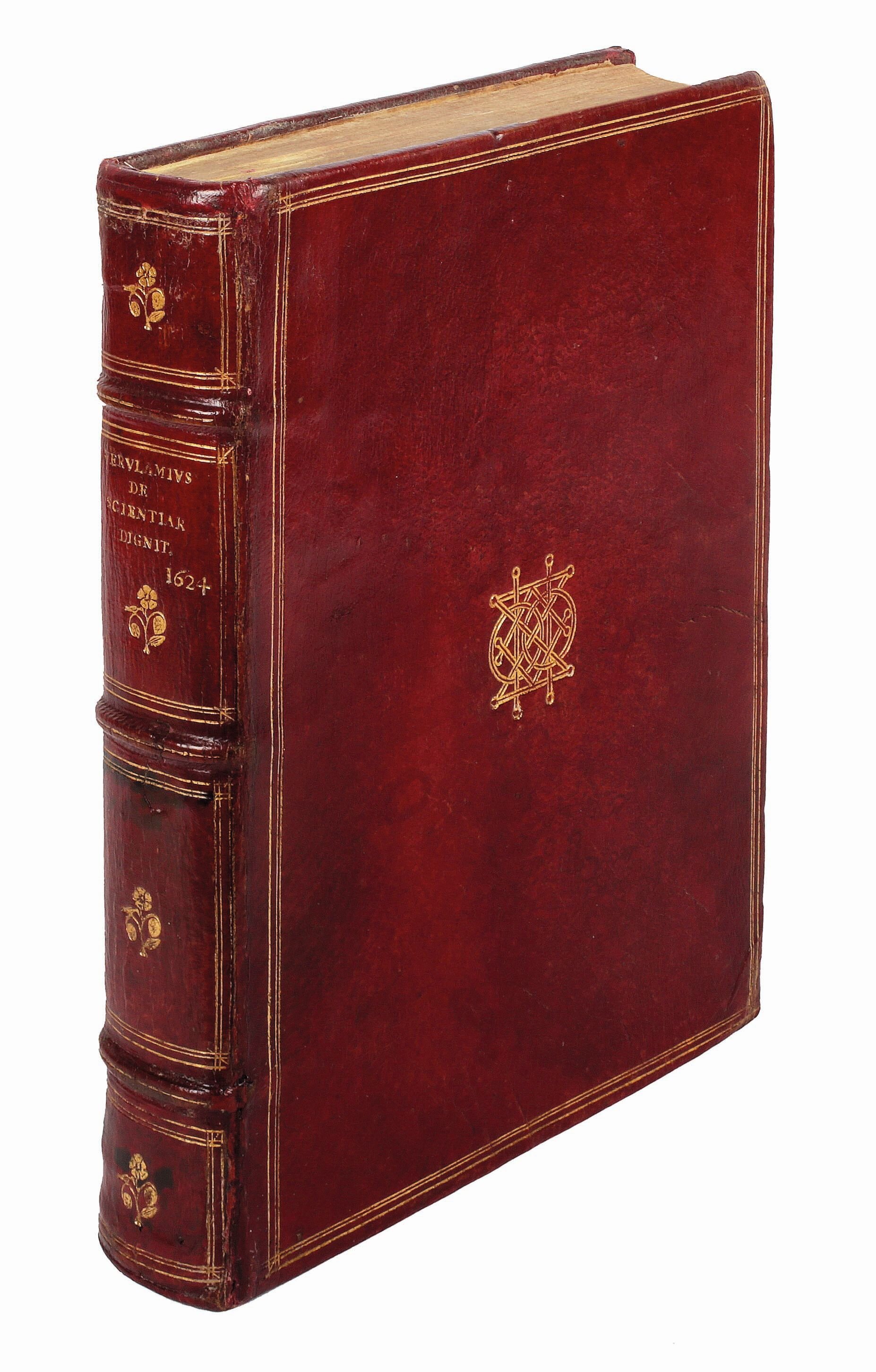

At the date of Gassendi’s arrival in Aix-en-Provence in March 1636, a copy of the Parisian edition of the De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum was still preserved in the large library Peiresc had amassed in his residence, elegantly, if plainly, bound in red morocco by his binder Simon Corberan, who had moved from Paris to Aix in 1625.

The covers are simply framed by triple gilt fillets, and Peiresc’s Greek cipher – two sets of his initials, ‘Ν Κ Φ’ – are stamped in gilt at the centre. As Gassendi reports,

[T]hose [books] which he bound for his own use, he would have his Mark stampt upon them. Which Mark was made up of these three Capital Greek Letters, Ν Κ Φ, which were so neatly interwoven, that being doubted, they might be read to right hand, and to the left by which initial capital Letters, these three words are designed, Nicolas, Klaudius, Phabricius.

(P. Gassendi, The Mirrour of True Nobility and Gentility, pp. 195-196).

The spine is decorated with small floral tools, with the second compartment bearing the title in gilt lettering, supplemented with the imprint date, ‘VERVLAMIVS DE SCIENTIAR. DIGNIT. 1624’. In fact, Corberan was among the first binders to stamp the publication date on the spine of books, a feature which – along with the Greek monogram – makes Peiresc’s volumes recognizable at first glance.

In De rebus coelestibus commentarii – included in the fourth volume of his Opera Omnia (Lyons 1658) – Gassendi presents a great number of observations recorded from studies performed over the decades, including those carried out at Aix-en-Provence in March 1636 together with his friend Peiresc. Gassendi’s sojourn lasted at least until the end of the month, as evinced by his inscription on the title-page of this very copy of the 1624 De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum, where he writes about having received the volume as a gift on 26 March 1636: ‘donum optimi d[omi]ni de Peiresc, ideo acceptum, quòd aliud exe[m]plar in folio hab[ea]t. 26 mart. M.DC.XXXVI. Gassendi’.

Peiresc’s generosity towards his friends was legendary. Once again, we can resort to the words of the recipient of this precious gift, Gassendi himself:

It is incredible to tell, how it should therefore come to passe, that he left not a most complet Library behind him: but neither of these will seem strange if a man shall consider, that he sought Books, not for himself alone, but for any that stood in need of them […] For as for such Books as were commonly to be had at the Book-sellers, of them he was wonderfully profuse and lavish. For which cause, as often as he was informed of Books newly come forth, he would have of them, which he would partly keep by him, and partly distribute them immediately among his friends, according as he knew they would like the subject matter thereof.

And whether he gave them away, or kept them, he would be sure to have them neatly bound and covered; to which end, he kept an industrious Book-binder in this House, who did exquisitely bind and adorn them.

(P. Gassendi, Mirrour of True Nobility and Gentility, pp. 194-195).

Indeed, the story of the present copy of Bacon’s De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum has yet another meaningful protagonist, albeit one less famous than Peiresc and Gassendi: the artisan who bound the volume for Peiresc: the ‘industrious Book-binder’ Simon Corberan, whose role was, however, not limited to the execution of this exquisite binding in red morocco, marked with the Greek monogram of his patron.

Rather surprisingly, Peiresc also trained his domestics in astronomy, as he reported in a letter of 30 May 1636 to his friend Thomas d’Arcos (1573-1637?), written only two months after Gassendi’s sojourn at his residence:

There is much pain and difficulty with celestial observations, but much less than you might imagine, as I have had performed, in diverse locations, and by simple gardeners, simple librarians, book-binders, masons, and other artisans who may seem less than amenable, such tasks that never fail to succeed quite well.

(Lettres de Peiresc, VII, Paris 1898, p. 180, our transl.).

Notably, Peiresc’s best assistant was none other than the binder Corberan, who had begun to observe celestial bodies on 7 November 1631, during the transit of Mercury, which had been accurately predicted by Johann Kepler, and even sketched a cahier d’observation. In March 1636, Corberan assisted Peiresc and Gassendi in their astronomical observations, and his continued passion and curiosity for astronomy is documented even after Peiresc’s death on 24 June 1637, when he and Gassendi observed a solar eclipse in 1639.

Although in his will Peiresc left books – along with mathematical and astronomical instruments – to Gassendi, his nephew refused to let the philosopher have them. The library was thereby dispersed, and a manuscript catalogue now survives in the Bibliothèque Inguimbertine at Carpentras. The present copy is therefore of especial interest as it rescues a volume from Peiresc’s library, and one, moreover, that helps elucidate the circulation of Bacon’s ideas and work within French intellectual circles of the 1620s and subsequent decades.

However, this precious copy of Bacon’s De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum places the emphasis first and foremost on friendship, learning, and the advancement of science. The collaborative venture undertaken by three men – a great patron and champion of learning and letters, a renowned philosopher and astronomer, and a keen and curious bookbinder, who spent nights observing planets and stars from an observatory in Provence in March 1636 – provides an ideal reflection of Bacon’s conviction that the true progress of knowledge can be achieved only through collective enterprise.

How to cite this information

Margherita Palumbo, “A gift from Peiresc to his friend Gassendi” PRPH Books, 15 June 2020, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/bacon-peiresc-gassendi. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.