The Times They Are A Changin’ in the Rare Book Trade

This October marks six years since Filippo Rotundo and I started our new venture in the United States. We opened PRPH Rare Books on October 23, 2013, with an extraordinary speech by Umberto Eco, who had just returned from his lectiones magistrales at Yale University and at the United Nations.

Five years ago, the president of ILAB at the time, Norbert Donhofer, went to Lucca with Filippo and then-president of ALAI Fabrizio Govi to meet the qualified scholars and bibliophiles gathered at the Biblioteca Statale for a conference on the life, work, and collections of Giuseppe Martini (1870-1944), the most important Italian antiquarian bookseller of his day. A contemporary of Leo S. Olschki and Ulrico Hoepli, Martini was called by Mario Armani, later director of the Libreria Hoepli, “l’homo bibliographicus”. The presence of the ILAB President, just after his meeting in Naples with the prosecutors of the Gerolamini affair, once again demonstrated ILAB’s ongoing support of the ALAI in what was arguably the most difficult moment in the living memory of the Italian trade.

Moved by this conference, I had the chance of dealing with some incunabula belonging to Martini, whose library is considered one of the richest private collections of Italian literature in the world. Reconsidering them some years later in light of PRPH’s sixth anniversary invites me to consider how our profession has been changing, and to offer reflections on the evolution of the booksellers’ job in the 20th century.

FORESI, Bastiano. Libro chiamato Ambizione. (Florence, Antonio di Bartolomeo Miscomini, ca. 1485).

CLIMACO, Giovanni S. Climacho altramente Schala Paradisi. Venice, Benalius and Capcasa, 1491.

In the 19th century, a bookseller rarely sold a book, regardless of its importance, with a bibliographic description. As illustrated on the right, at the beginning of his career Martini started quoting the bibliographic records directly on the flyleaves of incunabula in pencil as well as in pen – a practice which would now cause nightmares for booksellers and librarians.

Later, he would glue (!) cards with his longer descriptions. This became the custom at the time and remained the accepted practice until roughly 40 years ago.

PULCI, Luca. Il Driadeo d'Amore. Florence, Laurentius Alamanus, 1479.

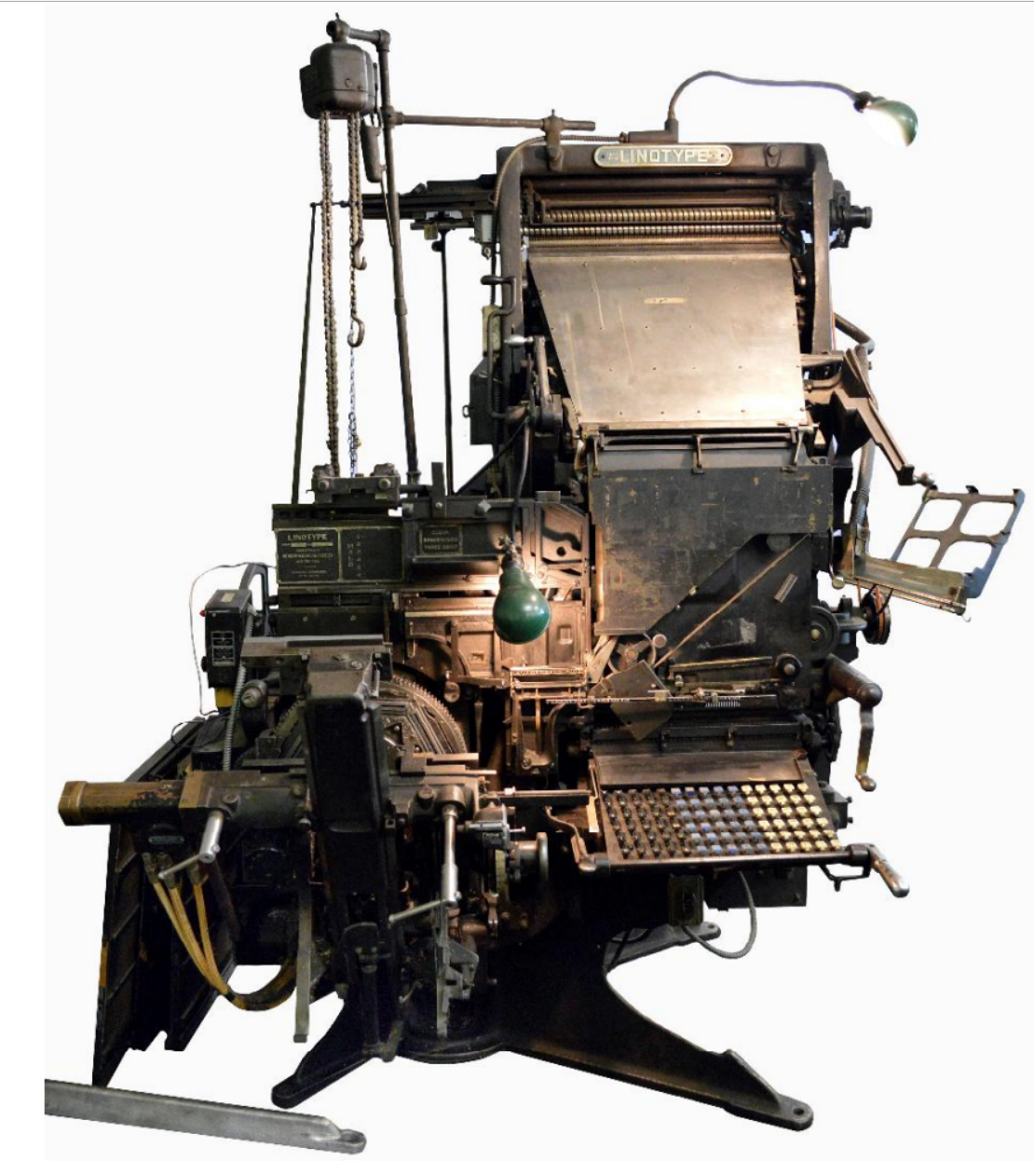

Linotype Model 31

Linotype Company, late 1940s

Norbert and I are old enough to remember – Filippo wouldn’t – when booksellers started to provide books with typewritten descriptions. When we both began working in the trade, we used to type on cards for the printers of our first catalogues, underlining in red or blue pencil, just as Martini did, what we intended to be printed in bold or italic. The catalogues were composed with a linotype machine: by pressing down on the keys of a large keyboard, the compositor used to typeset the text in lines of metal ready for the press.

We also had to physically go to the printer to check the proofs for correction: as the compositor had to replace the entire line of a page to correct a single letter, further mistakes were common, so I preferred to be present. Not to mention the complex process for reproducing illustrations or bindings in the catalogue: we used metal plates not so different from the ones that Aldus employed in his Poliphilo.

So, when Norbert and I began, it was indeed a very different world: computer, fax, scanner did not exist, and the internet? Inconceivable!

These colour-coded cards were archived as permanent records by the bookseller. With the advent of the computer, these records were transferred to files that could be enriched over time and carefully adapted to be used for multiple copies of the same title. Only in the early 1980s was linotype replaced by offset lithography printing, and later by computer typesetting and digitalized images.

With the arrival of the computer, booksellers’ descriptions became more comprehensive and elegant. But they were yet to benefit from the most recent step in technology which has revolutionized our work as well as that of collectors: the sharing of information through the Internet, which has allowed us to form a huge archive – updated continuously – of millions of descriptions of books on the market, and of even more books in libraries, complete with collations.

While until about 15 years ago few professionals had the tools for verifying the completeness and rarity of a book, buyers can now easily check the accuracy of a description. In addition, online offerings of a great number of titles has undoubtedly produced greater transparency than in the past: if the various search engines locate only one or two copies of a book, its rarity is immediately confirmed. This was a radical change for bibliographic work.

The paradox is that although the tools have made work easier, there is more work to be done. This has delayed the production of catalogues, as has the desire to produce an accurate and elegant catalogue. The one benefit to booksellers has remained unchanged: their pleasure in studying and understanding the books with which they will someday part.

Giuseppe Martini, whom Norbert celebrated five years ago, had among his many merits spreading his erudition and appreciation – in addition to his commercial activity. Achille Pellizari, author of the catalogue published by Martini-Hoepli, once wrote that Martini “had memories of bibliophiles he had never met, once writing a six-page entry for a manuscript in a sales catalogue which was not for sale!”

Much has changed in little more than a century of bibliophily. But what really matters remains unchanged: the task of the bookseller is also to disseminate culture by thorough study of the work, accurate descriptions, and the precise condition evaluation of the copy – all of which transcend commerce. Just as Martini did, a dealer should even now stimulate the curiosity of the collector, encourage bibliographical research, the conservation of cultural heritage, and the re-evaluation of what was not yet well known or has already been forgotten.

An accurate catalogue of any antiquarian bookseller is a formidable instrument of culture handed down to posterity. “When a writer dies, he embodies the books he has written” Jorge Borges declared. Paraphrasing his significant quotation, we could say that a rare-book dealer will always live on in the catalogues he or she has published. Though very few memories might remain of the books that have been purchased and sold, it is the collection of one’s own catalogues that is the bookseller’s true spiritual last will, the story of their life and of how they were able to “sell their own soul,” since every sale offered the opportunity to share their knowledge and passion with and amongst their fellow bibliophiles.

In 1921 my grandfather, ten years after opening his dusty bookshop, and while Martini was at his top, published Catalogue No. 1, offering 400 books, the most expensive one being an incunable offered for 65 liras.

Since then the changing of generations has added innovation and modernity to the methods of the profession. In 1998 I published A century before the CD-Rom, an original celebration towards the end of the twentieth century of the Italian Novecento books printed by skilled craftsmen (even after Martini was already dead). I chose a title that would emphasize the great distance between the traditional printing and digital reading. At the time, who could imagine the arrival of the e-book? Then, we came up with the new idea of a mutual catalogue with our friends at Libreria Philobiblon: The Battle of the Books (the title from Swift, of course), in which, in a spirit of friendly competition, each of us presented a book against another with similar characteristics.

Fun and games indeed, but between books and new technologies we also found a way to present an interactive and playful “catalogue” which was actually a DVD devoted to books and manuscripts of divination or fortune – Fanti, Spirito, Marcolini. As these books were designed to be games, we wanted viewers to “play” them. Many innovative projects have been realized in conjunction with Libreria Philobiblon, long before Filippo Rotundo and I founded PRPH Rare Books in New York. The most ambitious one was Myriobiblon, a series of four substantial volumes devoted to the Renaissance printing of Greek: Lexica, Authors I-II and Liturgical books.

Filippo and I strongly believe that our job is to foster the passion for the past by keeping pace with the challenging innovations of the future, but these kinds of shared projects realized by booksellers from different cities could not have been possible even 25 years ago, without the technological advancements in communication.

Giuseppe Martini, in his extraordinary journey – From Lucca to New York to Lugano, between 19th and 20th century (the title of the conference) – proved, in his day, that even without the technological supports we now enjoy, he was a great and innovative bookseller.

We believe a good catalogue can also be considered a little consolation for the bookseller himself: as I often say, that peculiar copy of a book, with its defects, waterstains, signatures, will remain a little bit mine forever, even after I have sold it to a client. Achille Pellizzari describes a similar feeling: “What more could Martini have done to say goodbye to these friends and companions in life? And this is the book of memories: all that remains of so much love, so many sacrifice, in the empty house.” He wrote this at the very end of the preface to the catalogue of 1954, on the tenth anniversary of Martini’s death.

In the same spirit, we celebrated the 750th anniversary of Dante’s birthday with an extraordinary catalogue illustrating many treasures among the manuscripts, incunabula, and editions of the Commedia and other texts of the great poet that have appeared up until the 20th century.

Besides the economic incentive, I cannot help but consider the intellectual enrichment involved in book dealing as a truly gratifying reward. When I was a young boy I had the chance to meet many of the greatest booksellers of yore, and since then, for almost 35 years, I have had the good fortune of sharing many more experiences in books, wine, and life with my fellow dealers.

Though, as Dylan says, the times they are a changin’, I believe the exchange of views with Filippo and other booksellers all over the world remains an irreplaceable resource in our unique profession.

A version of this article originally appeared on ILAB, published Oct. 21, 2015. https://ilabprize.org/articles/times-they-are-changin-rare-book-trade