The Mighty Tiber, Past and Present

In 2017, we offered the Bibliotheca Hertziana in Rome – part of the Max Planck Society and one of the world’s most renowned research institutes for art history – two folio albums bearing on the front cover the gilt inscription Vedute del Tevere in Roma prima della sua Sistemazione. The albums contain a series of albumin photographs taken on behalf of Italian authorities in 1887-1888 by the well-known Studio of the D’Alessandri Brothers. The goal of this photographic project was to document the course of the Tiber through Rome, before and during the erection of the vertical embarkments planned for protecting the city from the floods that had so frequently afflicted it throughout history. The first album is dedicated to the right bank (Sponda Destra, with 41 photographs), while the second is reserved for the left (Sponda Sinistra, with 53 photographs).

The two-volume Vedute del Tevere in Roma prima della sua Sistemazione, now in the Bibliotheca Hertziana, seated in Palazzo Zuccari, Rome (for the history, mission and images of the seat of this Library, at Palazzo Zuccari see https://www.biblhertz.it)

The construction of these muraglioni engendered a radical transformation of the city’s architecture and landscape. The sinuous course of the Tiber was modified and confined within embarkments, and numerous buildings, churches and bridges were destroyed: thus not only is this copy of the Vedute del Tevere in Roma prima della sua Sistemazione of the greatest rarity in its level of completeness, but it also represents an extraordinary resource for rendering and remembering the image of Rome’s Past.

Since antiquity, floods have been a very serious problem for Rome, owing to the irregular flow of the Tiber and the varied topography of the city’s alternating hills and valleys, along with the city’s location at a point where the river was more liable to flooding. Numerous primary sources document the powerful inundations of Ancient Rome, beginning with that of 414 BCE which was narrated by Livy in his Historiae. Although the Romans had the engineering skills necessary for erecting embarkments and avoiding major destruction, in this regard they were “surprisingly resilient” and seemed to have predominantly relied on their “commendable flexibility”:

The city proved to be surprisingly resilient, and the Romans’ attitude toward inundations was also marked by commendable flexibility. Romans were willing to cede a measure of independence to Father Tiber. Despite its very real potential for destruction, the Romans maintained toward the river in their midst an attitude of acceptance of its transgressions as well as respect for its power” (Gregory S. Aldrete, Floods of the Tiber in Ancient Rome, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006, 238-239).

A plaque on the façade of the Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. It is dated 8 October 1530, when the water rose 18.95 meters above sea level.

The ‘transgressions’ of Father Tiber continued into the following centuries, and there are still dozens and dozens of stone markers scattered throughout the city, on façades of churches or palaces, testifying to the Roman floods and the great heights reached by the river’s waters. This is the case for a plaque that is still clearly visible on the façade of the Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva: located in one of the lowest points of Rome, the Campo Marzio district, the plaque records the dramatic inundation of 1530, when the water level reached a height of 18.95 meters above sea level, flooding a large portion of the city, and causing considerable damage.

Flood markers on the on the façade of the Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva.

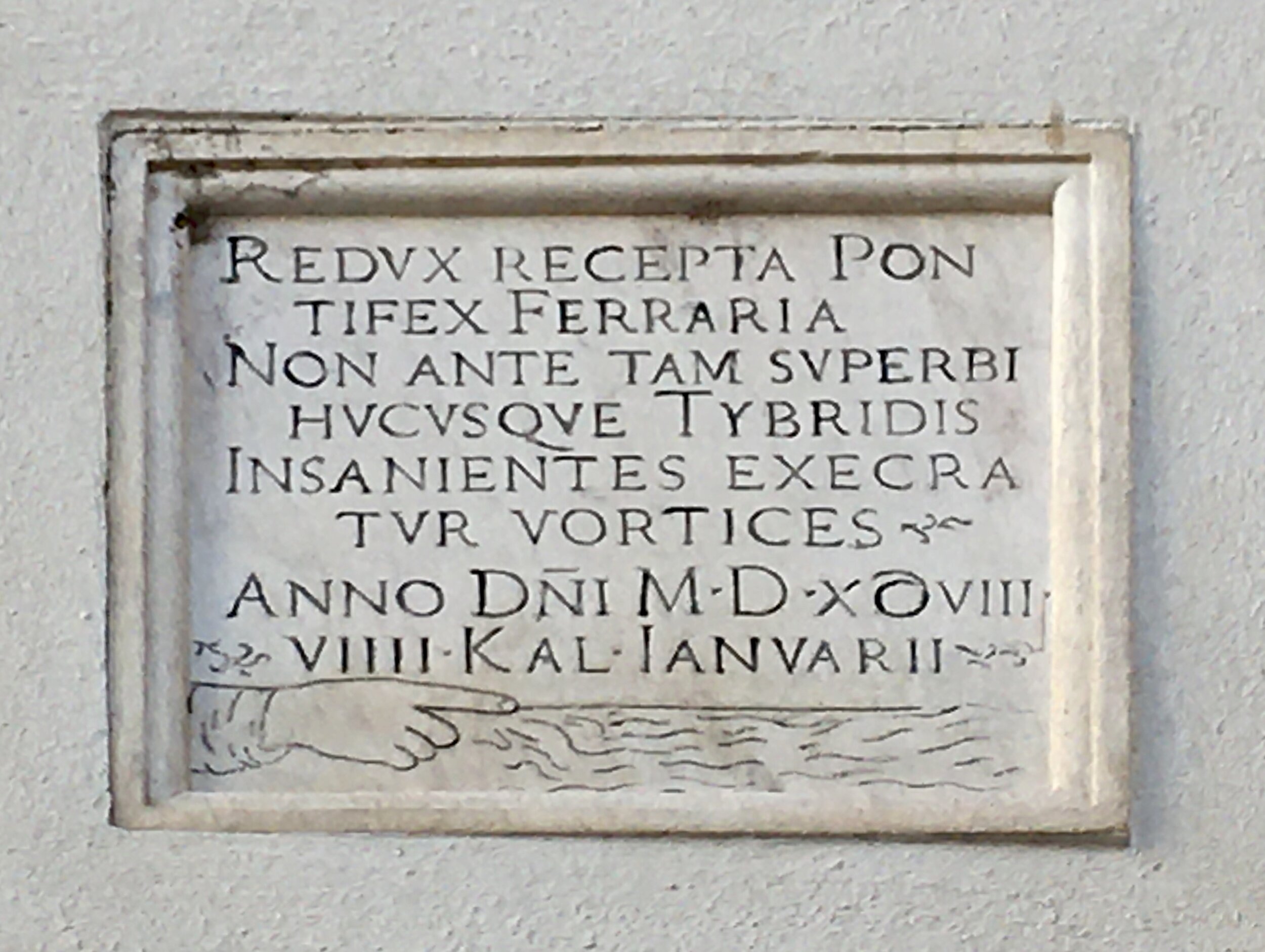

A plaque at the Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva marking the flood of 1598, Rome’s worst ever.

Rome’s worst flood was the one that occurred on 24 December 1598, when the water reached a dramatic 19.56 masl (12 feet above the present street level), a level that was then maintained for three days. On this occasion, the ancient Aemilius Pons – the oldest stone bridge in Rome, located near Tiber Island – was destroyed. The bridge’s single remaining arch, in the middle of the river, was thenceforth called Ponte Rotto, i.e. the Broken Bridge.

The Ponte Rotto, i.e. the Broken Bridge, near Tiber Island.

A ‘floating’ Fatebenefratelli Hospital: in recent days, intense rain has caused the river’s water to rise high again, completely submerging Tiber Island’s distinctive travertine platform.

The popes were aware of Rome’s vulnerability to floods. In 1704, during the pontificate of Clemens XI, the Ripetta Port was erected on the left bank of the Tiber. The papal architect Alessandro Specchi (1668-1729) projected an elegant, curvilinear flight of steps descending from the church of St. Girolamo degli Schiavoni to the shore of the river.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Veduta del Porto di Ripetta, ca. 1750, engraving. Public domain.

That Baroque scenography, which no longer exists, also included two marble columns for marking the height of floods, which have since moved to Piazza del Porto di Ripetta.

Columns with flood markers from the old Porto di Ripetta, now located at the Piazza del Porto di Ripetta.

A few years before, Clemente XI charged the Dutch engineer Cornelius Meyer (1629-1701) with a major project aimed at protecting the Via Flaminia against the flooding of the Tiber. Meyer, whose plans were less expensive than those proposed by the project’s former head engineer, Carlo Fontana (1638-1714), constructed a passonata, i.e., a row of piles, in the Tiber, which deflected the river’s current away from the Via Flaminia.

After this first successful work on the Tiber, Clement X and his successor Innocent XI hired Meyer to improve navigation on the river with the purpose of increasing commerce. Meyer came up with revolutionary solutions to expedite travel along the river and in 1683, with the help of artist Gaspar van Wittel (1653-1736), he published his projects in L’arte di restituire a Roma la tralasciata navigatione del suo Tevere, the second issue of which appeared in 1685 (see a description of Meyer’s work included in a two-volume, ‘Ex dono Auctoris’ set available here).

Meyer, Cornelius (1629-1701). L’Arte di restituire à Roma la tralasciata Navigatione del suo Tevere. Divisa in tre parti.... Rome, Giacomo Antonio de Lazzari Varese, 1685.

See more about this work here.

However, Meyer’s passonata project could offer only a partial solution. Floods occurred frequently throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, as testified by, among other things, the stone marker located at Via dell’Arancio, then not far from Ripetta harbour, dated to 1805. There one also finds a hydrometer for measuring the water level.

A hydrometer in Via dell’Arancio.

In September 1870, Rome was annexed to the Italian Reign. On 29 December, a mass of water inundated the city once again, this time reaching the notable level of 17.22 masl, earning it the title of ‘The Great Flood’.

A plaque recording the water level during the ‘Great Flood’ of 1870, when the water reached 17.22 meters above sea level.

Obviously, the clergy regarded it as a divine punishment for the Act of Sacrilege committed against the Catholic Church. The damage caused by the flood was conspicuous, the city was overwhelmed with mud and flotsam of all sorts, and the flour mills established near Tiber island disappeared entirely.

The new Italian administration decided the city could no longer go through similar catastrophes. After ca. 2,500 years of flooding, it was time to bring the unpredictable waters of Father Tiber under control. This was to be done with the erection of massive embarkments along its S-shaped course. On 31 December 1870, Rome had officially been declared the new capital city of the Italian Reign. Such an ambitious civic project would present the world with a new image of Rome, now safe and healthy.

A commission was appointed in January 1871 with the goal of evaluating the various plans being proposed for the project. That of hydrologic engineer Raffaele Canevari (1828-1900) was chosen, which entailed the erection of continuous, vertical embarkments on both sides of the Tiber, as well as the construction of boulevards running along its course, i.e., the well-known Lungotevere, the Tiber waterfront.

View of the Lungotevere of the left embankment. The Lungotevere (Tiber waterfront) was built to control the restless waters of the Tiber river.

Daily life on the Lungotevere.

The project had its costs, however, and not only financial ones. The construction of the massive embarkments necessitated the destruction of several buildings, churches, and bridges. The construction allowed for great new buildings to be established, as with the Great Synagogue of Rome, but the architecture at the heart of the city was still irreparably upset, and entire parts of the Tiber landscape, which had been the source of countless drawings and paintings, definitively disappeared.

Among the numerous ‘victims of excellence’ on the right bank were the church of S. Salvatore de Pede Pontis, located in front of Tiber Island, and the Ripa Grande Port; the left bank lost forever, among others, the Ripetta Port, and the original district of Tordinona, which was entirely demolished.

Remains from the old Porto di Ripetta, now located at the Piazza del Porto di Ripetta.

View of the right embankment with the Great Synagogue of Rome (1901-1904). One of the largest synagogues in Europe, it was built in the area of the old Roman Ghetto, which was largely demolished during the construction of the embankment walls.

Fortunately, in 1887 the Genio Civile (i.e. the civil engineers of Rome) commissioned a series of photographs documenting the banks of the Tiber before and during the construction of the embankments. The photographic campaign was entrusted to the renowned Studio (or Stabilimento Fotografico) D’Alessandri.

This studio was established in Rome in 1856 by Antonio D’Alessandri (1824-1893), a priest born in L’Aquila, who was also the official photographer to the Papal Court until 1870. Murray’s A Handbook of Rome and Its Environs (London 1862) described his establishment as the ‘first Studio’ in the city, and it was active — first at via del Babuino no. 65, and then as of 1865 at via del Corso nos. 10-12 — until 1950.

The excellent Roman photographer D’Alessandri took the pictures between 1887 and 1888 in partnership with his brother Paolo D’Alessandri (1827-1889), and the photographs were then compiled in the aforementioned albums titled Vedute del Tevere in Roma prima della sua Sistemazione.

The documentary value of the Vedute del Tevere in Roma prima della sua Sistemazione is crystal clear, and was immediately noticed by the Bibliotheca Hertziana, which also holds an outstanding Photograpy Collection, with over 870,000 photographs and negatives, mainly focused on Roman topography (see https://www.biblhertz.it/it/photographic-collection).

In 2017, the Library acquired the two albums, making it one of the few institutions in the world to own the complete series. In 2018, all the photographs were carefully catalogued and digitized, and the images are now visible on the Library’s website (https://foto.biblhertz.it/exist/foto/obj08121211).

This is not the only reason why we’re feeling proud. Recently, the Library decided to display reproductions of the original photographs on the walls of the reading room of the Photographic Collection, on the second floor of the stunning building which has housed the Bibliotheca Hertziana since 1913.

The exhibition – Momenti di trasformazione. Il Tevere a Roma – creates an impressive dialogue between Past and Present. It places the black and white images of the original Tiber banks, as photographed in 1887-1888, side by side with colour images realized in 2018 by the Hertziana photographer, Enrico Fontolan, in order to show their modern-day correspondents.

The exhibition opens with a panel offering a short description of the original photographs and highlighting their great documentary value. We translate the final lines of it here:

“[These photographs] are not only images of great beauty, exceptionally able to capture the atmosphere of the sites, but also precious and clear visual sources for many areas of the city, unique testaments to buildings, bridges and monuments that no longer exist.

The dramatic urban transformation is highlighted in the series of comparisons created by Enrico Fontolan (Bibliotheca Hertziana) in the Spring of 2018, following in the footsteps of the D’Alessandri Brothers.

Often, there are only scarce remains from the broad views of the Past. In many cases, it is near impossible to revisit the original views. Numerous bridges, buildings and streets did not yet exist at that time, but it is above all the romantic and rustic outline of the city that has been completely changed by the character of modern human life. The photographs made by the D’Alessandris are still true views, airy and open, while the modern images are often but glimpses, in which the real protagonists are the embankments, and the life rolling upon them”.

We invite you to discover the old romantic and rural outline of Rome and its river, through the exceedingly rare series of D’Alessandri’s photographs. These images have passed through our hands and are now preserved in the first-rank library of the Bibliotheca Hertziana, which has done such a great service to history and the community by highlighting and enhancing them, and by making them available for all to see. This is the second reason why we’re feeling so proud.

How to cite this information

Margherita Palumbo, “The Mighty Tiber, Past and Present,” PRPH Books, 27 January 2021, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/tiber. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.