Traveller through the Ages: Joyce's Ulysses Turns 100

Today marks the birthday of James Joyce (2 February 1882 - 13 January 1941) as well as the 100th anniversary of his masterpiece, Ulysses. Anniversaries were important for the Irish novelist, who was highly superstitious – the novel itself is set on a memorable day, 16 June 1904, the date of Joyce’s first walk with his future wife, Nora Barnacle – and he chose the publication of Ulysses to coincide with his 40th birthday for good luck. Lucky or not, the text would ultimately prove massively influential and is now universally regarded as a defining novel of modernist literature.

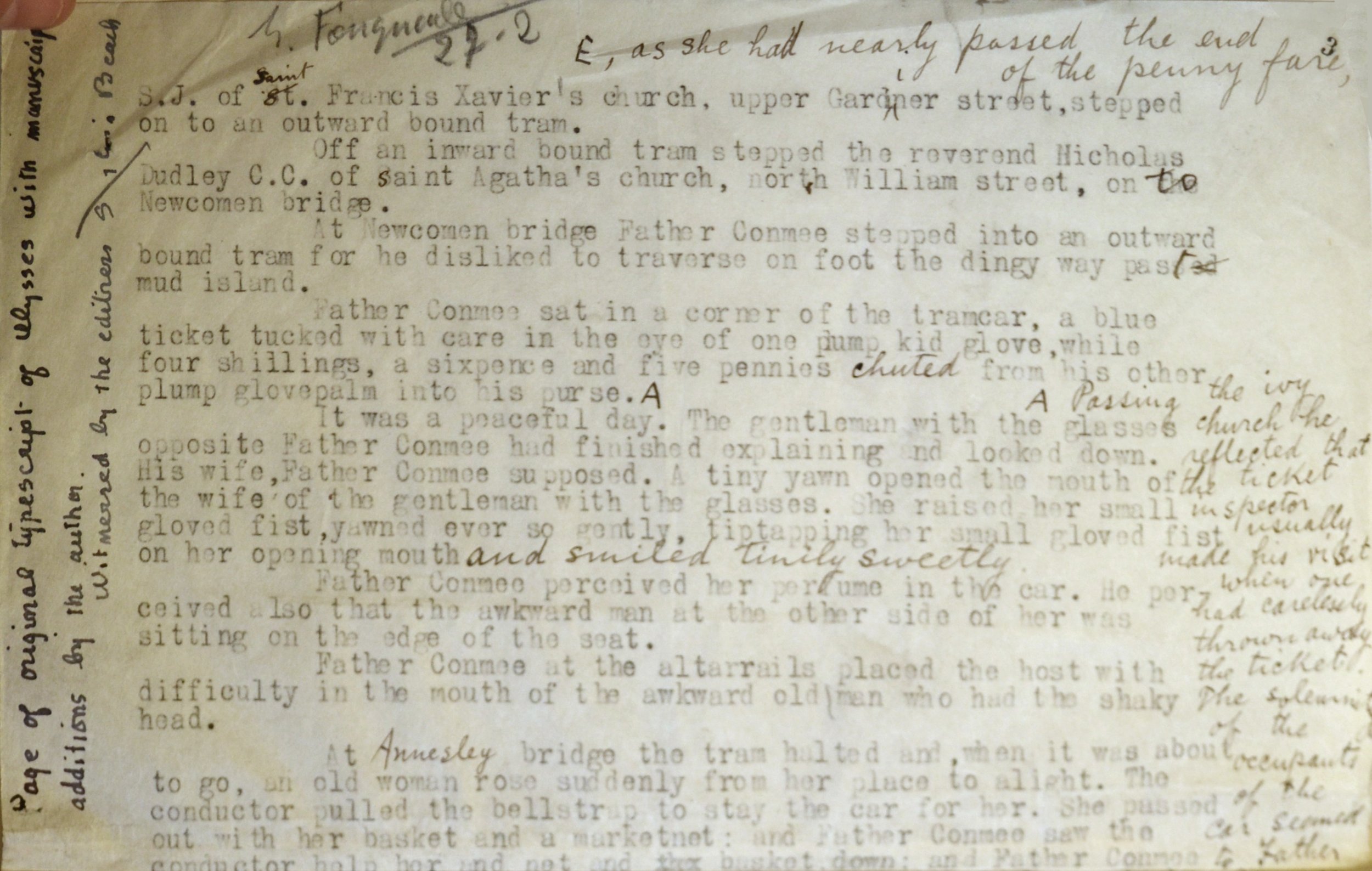

James Joyce (1882-1941). Ulysses. Paris, Shakespeare and Company, 1922.

Celebrations of the anniversary range far and wide, including a two-day conference, “Joycean Cartographies”, at the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens and a panel organized by Rare Books LA on The Novel of the Century. We at PrPh are taking a moment to reflect on a particularly special copy of the first edition of the book which was previously shown at our New York gallery along with the editio princeps of Homer (1488) and is now included amongst our sold masterpieces: a superb publisher’s presentation copy, inscribed by Sylvia Beach (1887-1962) – owner of the famed Parisian bookshop Shakespeare and Company and a central figure in the Parisian modernist literary scene, in addition to Joyce’s champion and publisher – to the art and book collector Tudor Wilkinson (1879-1969), together with an annotated leaf from the final typescript. An American expatriate settled in Paris, Wilkinson was influential in obtaining Beach’s release from a Nazi internment camp, and she presented this copy to him as a thank you.

Sylvia Beach at Shakespeare and Company, Paris, ca. 1920.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Beach was the daughter of a Presbyterian minister who first went to Paris with her family when she was 14 years old and settled there in her late 20s. There she met Adrienne Monnier, who would be her friend and lover until Monnier’s death in 1955 and whose bookstore and lending library, Maison des Amis des Livres, provided the model for Beach’s own Shakespeare & Company, which opened in 1919. Specializing in Anglo-American literature, the new shop was perfectly timed for the huge influx of American expatriates and burgeoning transnational scene of artists and writers that had converged in Paris after World War I. As the French writer André Chamson once said, Beach “did more to link England, the United States, Ireland, and France than four great ambassadors combined.” (Quoted in N. R. Fitch, Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation, New York 1983, p. 275)

Already in its first years, Beach’s shop became a central gathering spot for such literary giants (or future giants) as André Gide, Paul Valéry, Gertrude Stein, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Djuna Barnes, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Mina Loy, and Walter Benjamin. In addition to forging connections, introducing her gatherers to the latest experimental writing, and promoting their own work amongst the French public, Beach also helped with the myriad practical issues of working abroad, including finding affordable accommodations, printers, translators, and financial support; providing a mailing address and even loans, and circulating manuscripts to editors and publishers.

Her significance as a major player in modernist literary history was sealed with the publication of Ulysses. Beach met the self-exiled Irishman at a dinner hosted by French poet André Spire to welcome Joyce to Paris; the next day Joyce went to Shakespeare and Company and joined the lending library. Beach already acknowledged Joyce to be the most important writer of their time and given the difficulties he faced finding a publisher for Ulysses (parts of which had been deemed obscene after appearing in The Little Review), she stepped in and offered to publish it herself. Funding the publication partly through subscriptions and partly out of her own pocket, she worked closely and assiduously with Joyce and French typesetters unaccustomed to working with English text, let alone the author’s notoriously experimental and inventive use of language, and the work was published in just under a year.

The 1,000 copies of the first edition were sold exclusively by Beach’s shop and included 100 numbered, signed, and printed on Dutch handmade paper; 150 numbered and printed on vergé d'Arches; and 750 merely numbered. The magnificent copy presented here is number 24 of the 100 copies on Dutch handmade paper signed by the author. A special publisher’s presentation copy, it is also inscribed by Beach to Tudor Wilkinson on a card tipped-in on the front endpaper: ‘For Tudor Wilkinson | this copy of the 1st edition | of James Joyce's Ulysses | as a token of gratitude | from Sylvia Beach | Paris February 1943’. Beach's inscription echoes that written by Joyce himself in the copy of Ulysses (no. 2) which he gave to her, presented also as a ‘token of gratitude’.

Beach ultimately closed Shakespeare & Company in the late winter of 1941, after two separate visits from a high-ranking German officer, the second one threatening to confiscate her entire stock after she refused to show him a copy of Finnegans Wake. Beach removed all her inventory to an unused apartment upstairs and the shop itself remained intact, but in August 1942 Beach herself was interned in Vittel by the occupying forces. As documented in a series of unpublished letters written by Wilkinson to Monnier, now held in the Carlton Lake collection at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, Wilkinson was instrumental in securing her release by writing on her behalf to Jacques Benoist-Méchin, an ardent Joycean who had joined Beach's lending library in 1919, and was by this point active as a secretary at Vichy headquarters. Though clearly opposite in their politics, the literary bond prevailed and Beach was released in February 1943.

The ‘accomodationist’ Wilkinson was – with his wife the famous Ziegfeld performer Kathleen Marie Rose (a.k.a. Dolores Rose, whose own release from Vittel he is said to have secured by letting Hermann Göring have one of the paintings in his remarkable collection) – active in the French Resistance, and following her release Beach herself would also work with the cause.

James Joyce and Sylvia Beach, in her Paris office, 1921.

Also tipped-in at the beginning is an original black-and-white photograph of Joyce, Beach, her sister Cyprion, and John Rodker, inside Shakespeare and Company, which is also inscribed by Beach (‘Shakespeare and Company in the rue Dupuytren 1921 with James Joyce...’) along with a page of the typescript of ‘The Wandering Rocks’ episode of the novel, with Joyce’s autograph annotations, and further inscribed by Beach (‘Page of original typescript of Ulysses with manuscript | additions by the author’).

The typescript begins ‘...S.J. of St. Xavier's church, upper Gardiner street stepped on to an outward bound tram...’, and is a portion of chapter 10, the ‘Wandering Rocks’ episode, as Father Conmee travels on board a tram car between Newcomen bridge and Howth road, reflecting on the appearance, nature and behaviour of his fellow occupants both in general and in particular, leading on to a rumination on the propagation of the faith and of the millions of black and brown and yellow souls that had not yet received baptism (‘...But they were God's souls created by God. It seemed to Father Conmee a pity that they should all be lost, a waste, if one might say...’). Among Joyce's autograph annotations, comprising over 100 words in black ink, there are three typically enriching additions. These autograph revisions and additions by Joyce were made for the final printing of the first edition in the months leading up to its publication in February 1922. Aside from Beach's note relating to these (‘...Witnessed by the editress Sylvia Beach’) there is a printer's note in pencil at the head.

The single leaf (p. 3 of the complete typescript) is one of two such leaves separated from the main portion of the printers' typescript for this episode now kept in the James Joyce Collection at the University of Buffalo Libraries (V.B.8.a.i: see http://library.buffalo.edu/jamesjoyce/catalog/vb8ai.htm). The other leaf is the final page (p. 25), which Buffalo states as having been last recorded in the late Bernard Gheerbrant's Catalogue de l'exposition "James Joyce & Paris, 1902... 1920-1940... 1975: Papers from the Fifth International James Joyce Symposium (1979). The typescript for this and other episodes of Ulysses were prepared from the Rosenbach (‘fair copy’) manuscript version (itself prepared from Joyce's original notebooks), chiefly in Zurich and Paris between 1919 and 1920, though – as here – Joyce then made further autograph revisions in black ink for the final printing of the first edition.

Before these revisions the ‘Wandering Rocks’ episode had been among those portions of the text that appeared in the The Little Review (in the June and July issues of 1919).

Buffalo acquired the bulk of the final printers' typescripts of Ulysses from their acquisitions in 1950 and 1959 of (1.) the Joyce materials exhibited at La Hune in Paris after the war (essentially comprising the personal effects left in Joyce's Paris apartment when he fled in 1939) and (2.) Sylvia Beach's own collection of manuscripts, letters and books. It would appear that the present typescript leaf was removed by Beach from the rest of the ‘Wandering Rocks’ chapter – after publication of Ulysses and after the printer had returned the typescripts – specifically for the purpose of presentation.

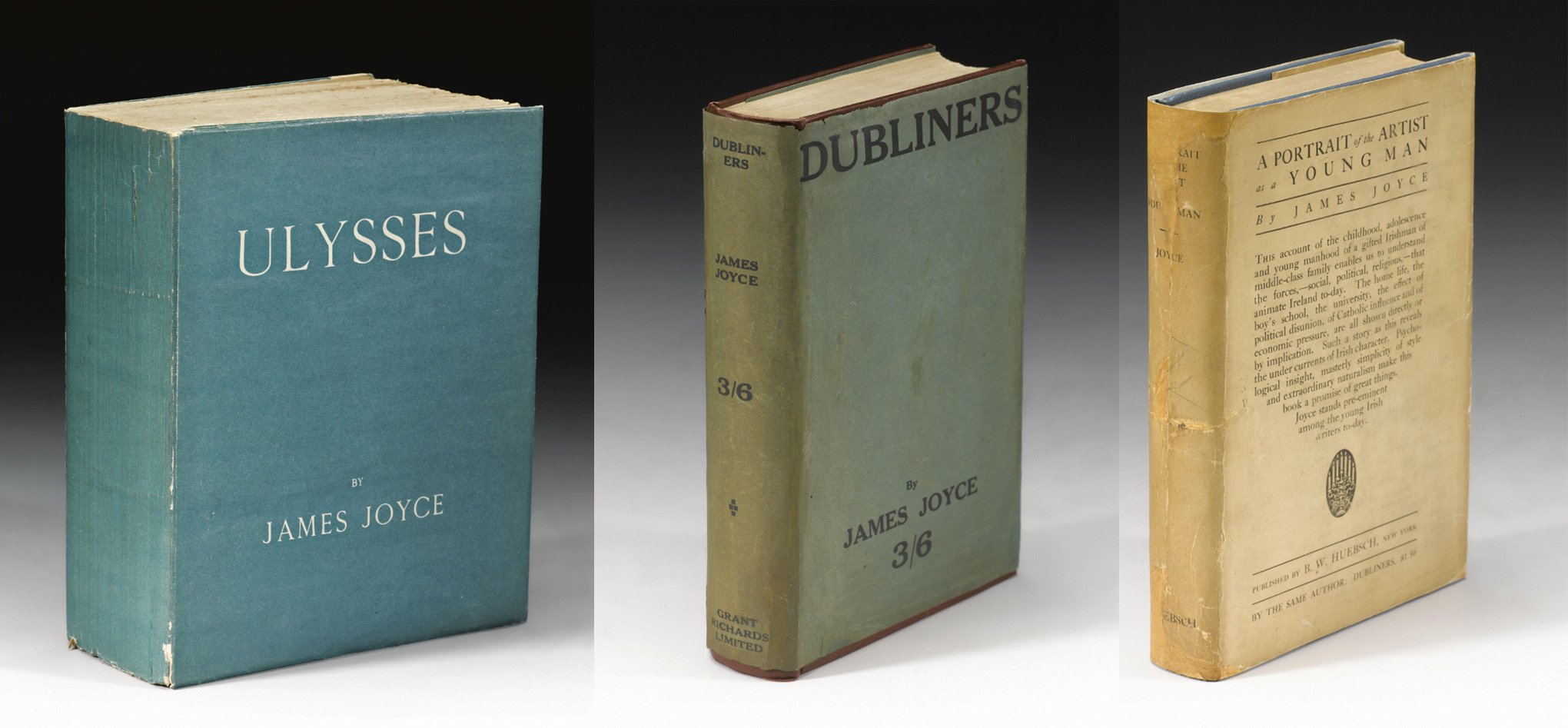

Extraordinary Joyce lots at Sotheby’s, The Library of an English Bibliophile, 20 October 2011.

The appearance, on 20 October 2011, of this extraordinary volume in Part II of Sotheby’s sale of The Library of an English Bibliophile, was obviously a major event and was discussed in the press. Stephen J. Gertz described it as “a jaw-dropping and superb Publisher's Presentation Copy” and “the superstar” of the sale: “A volume from rare book heaven and one of a handful of incredible copies of Joyce first editions.” (S. J. Gertz, “Superstar 1st Edition of Ulysses Estimated $450,000-$500,000 at Sotheby's”, 26 Sept. 2011) The sale also included the fine H. Bradely Martin copy, in the rare dust jacket, of the first published edition of Joyce's Dubliners (1914) – one of only 746 bound copies – as well as a fine copy, also in the rare dust jacket, of the first edition of Joyce’s autobiographical novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916).

Of course Gertz was right — the exquisite Ulysses stole the show, for still beyond the historical and bibliographical value of the copy, it presents such an intimate portrait of the woman behind the modernist masterpiece: a copy that meant so much to its publisher, of a book that means so much to its readers.