An Extraordinarily Rare Book: The 1564 Rampazetto Re-Issue of Marcolini’s Commedia

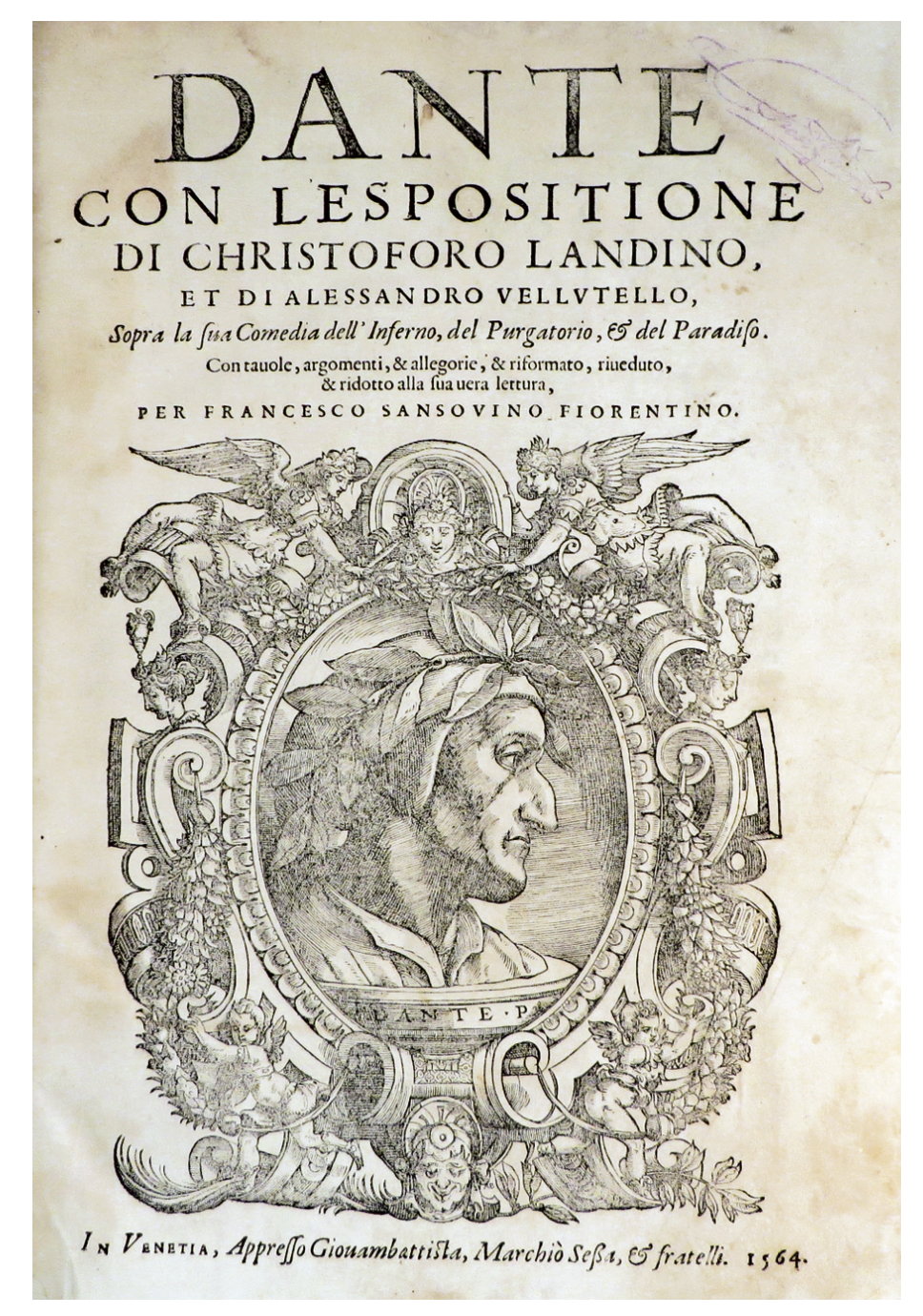

Title page of Dante Alighieri’s La Comedia di Dante Alighieri con la nova esposizione di Alessandro Vellutello.... Venice, Francesco Rampazetto, 1564 [at the end: Francesco Marcolini for Alessandro Vellutello, 1544].

See the complete description of this copy here.

Last week’s post sketched the afterlife of the Commedia published in 1544 by the Venetian printer Francesco Marcolini (ca. 1500-1559), especially that of its illustrative apparatus, which enjoyed large and lasting popularity, and was variously re-used (either partially or entirely) by other printers up until the end of the seventeenth century.

Dante studies have always paid particular attention to the most celebrated episode in the long life of the Marcolini woodcut cycle, namely, its complete re-use by the Sessa brothers for their famous Commedia of 1564 – known as the edition ‘del nasone’, i.e., ‘of the big nose’, owing to the large portrait of Dante on the title page – , which was edited by Francesco Sansovino, and included commentaries by both Cristoforo Landino and Alessandro Vellutello.

Title page from the Sessa brothers’ famous ‘del nasone’ edition of 1564.

Immensely popular, the Sessa Dante of 1564 was reprinted in 1578 and 1596. Much less is known, however, about the other Commedia that appeared in Venice in 1564: the re-issue of the Marcolini Dante of 1544, by another Venetian printer, Francesco Rampazetto.

Francesco Rampazetto is thought to have been born in Lases, in the northern region of Trentino, in the 1510s. He was active as a printer in Venice – in calle delle Rasse, near St Mark’s – from 1540 to 1576, and played a leading role in the Università delli Stampatori et Librari, i.e., the Guild of Printers and Booksellers, which was officially founded in 1571, although its existence is documented only as of 1549. After his death in 1576/77, Rampazetto’s printing house was run by his sons Giovanni Antonio and Giacomo, and later by his grandson Francesco the Younger, whose activity is documented up to the 1620s.

The beginning of Rampazetto’s career is generally dated to 1540, the year printed on the title-page of a booklet by Giovanventura Rosetti, the Plictho de l’arte de tentori che insegna tenger panni telle banbasi et sede, the first manual on the art of dyeing to have appeared in Italy. This was a technical work well-suited for the Venetian audience given the city’s thriving dye industry, which had, not coincidentally, made the lagunar city the center of production for books printed on blue paper (for the prominence of Venice in blue-paper printing see the catalogue, Italian Books II).

In the following years, Rampazetto’s activity was quite varied, alternating between official acts issued by the Venetian Senate, cheap books, literary works, juridical treatises, grammars, and even a few editions in Greek. Particularly noteworthy is his production of mottetti and madrigali, often printed on behalf of Girolamo Scoto. He also had business connections with other printers, mainly with Melchiorre Sessa and his heirs, on whose behalf he printed several editions, mostly literary works. Rampazetto’s catalogue also reveals, however, his attitude toward re-proposing editions previously issued by other Venetian printing presses. His main ‘templates’ were those by Bartolomeo Imperadore, Giuseppe Comino da Trino, and above all Francesco Marcolini.

From the title page of Rampazetto’s Comedia.

Rampazetto’s activity is in fact especially linked to that of Marcolini. After his death in 1559, Rampazetto either inherited, purchased, or in some other way came into possession of a portion of Marcolini’s typographical materials. It is believed that he may have also borrowed equipment – such as music type fonts, initials, and other decorative elements – from the Scoto press, but Marcolini’s legacy is unquestionably more profound. It is in fact not a mere transfer of property in the form of punches or woodblocks. From 1560 onwards, Rampazetto’s catalogue contains an impressive number of works which had notably marked Marcolini’s successful career as a printer, and which Rampazetto published with renewed typographical appearances, often thanks to his partnership with the Sessa brothers who served as financial backers.

We mention here only a few examples. In 1561, Rampazetto published a well-known musical edition already published by Marcolini in 1558, the Introduttione facilissima, et novissima, di canto fermo, figurato, contraponto semplice, et in concerto by Vincenzo Lusitano. The aforementioned Libro Terzo of the Regole generali di architettura by Sebastiano Serlio followed in 1562, and the Imagini con la spositione dei Dei de gli antichi by Vincenzo Cartari, whose first edition had been printed by Marcolini in 1558, appeared in 1566.

Rampazetto also ‘inherited’ one of the eccentric and transgressive writers and poets with whom Marcolini had had a close relationship: the Florentine Anton Francesco Doni (1513-1514). Doni’s Zucca – first issued by his predecessor in 1551-52 – was re-proposed by Rampazetto in 1565, and the Rime del Burchiello commentate dal Doni found a similarly ‘new life’ in 1566, after its first appearance by the Marcolini press in 1553.

This ‘new life’ for editions previously printed by Marcolini is only mostly superficial. All the books mentioned above are merely renewed through the modification of volume size, setting the text in different types, or adding decorative elements coming from Rampazetto’s own equipment. Apart from these physical features, the content is unchanged, its divisions into parts or chapters entirely unaltered, and the textual variants are mostly detectable only in a slightly different use of majuscule letters and punctuation. Even the ‘old’ prefaces or dedicatory epistles are reprinted, with little concern for whether or not the paratextual materials praise his predecessor as the printer or contain details that were, by then, out of date. Such instances clearly reveal Rampazetto’s urgency in printing, possibly in order to anticipate other Venetian typographers, once Marcolini’s privileges, granted by the Venetian Senate, had expired.

It is with this context of reprinting, refreshing, and substantial recycling, that Dante and his Commedia made their appearance at Rampazetto’s printing house in 1564.

This episode is still rather unknown in the publishing history of the poem, having gone unnoticed in the standard Dante bibliography, and without any trace in the catalogues of Italian institutional libraries. Until now, the existence of Rampazetto’s Commedia was known only in a unique and incomplete copy preserved in the John A. Zahm Dante Collection at the University of Notre Dame. The Zahm copy was presented on the occasion of the exhibition “Renaissance Dante in Print (1472-1629)”, which took place at the Hesburgh Library and the Newberry Library in Chicago in 1993-1994 (see https://www3.nd.edu/~italnet/Dante/). It was defined there as a “curiosity in the annals of early Dante publishing”.

The title closely recalls that printed by Marcolini in 1544.

Title pages of Dante’s Comedia as printed by Marcolini in 1544 (left) and in Rampazetto’s re-issue of 1564 (right).

At first glance, La Comedia di Dante Aligieri con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellutello of 1564 has the appearance of a new publication, and its title-page even suggests that a privilege was granted by the Venetian Senate – ‘CON GRATIA ET PRIVILEGIO’.

The prefatory materials correspond exactly to those appended to the 1544 Commedia: the volume opens with Vellutello’s brief dedicatory letter to Paul III, which bears no textual differences but is now set in a larger italic font. The space for a capital left blank by Marcolini is also now filled with a woodcut animated initial, thanks to the large array of decorative elements in the hands of Rampazetto, previously owned by other Venetian printers.

Vellutello’s brief dedicatory letter to Paul III, from Rampazetto’s 1564 re-issue of Marcolini’s Commedia.

The Rampazetto Dante seems, therefore, to be a close reprint of the Marcolini one, nothing more than a publishing initiative similar to his reprints of Serlio’s Regole generali di architettura of 1562 or Doni’s Zucca in 1565.

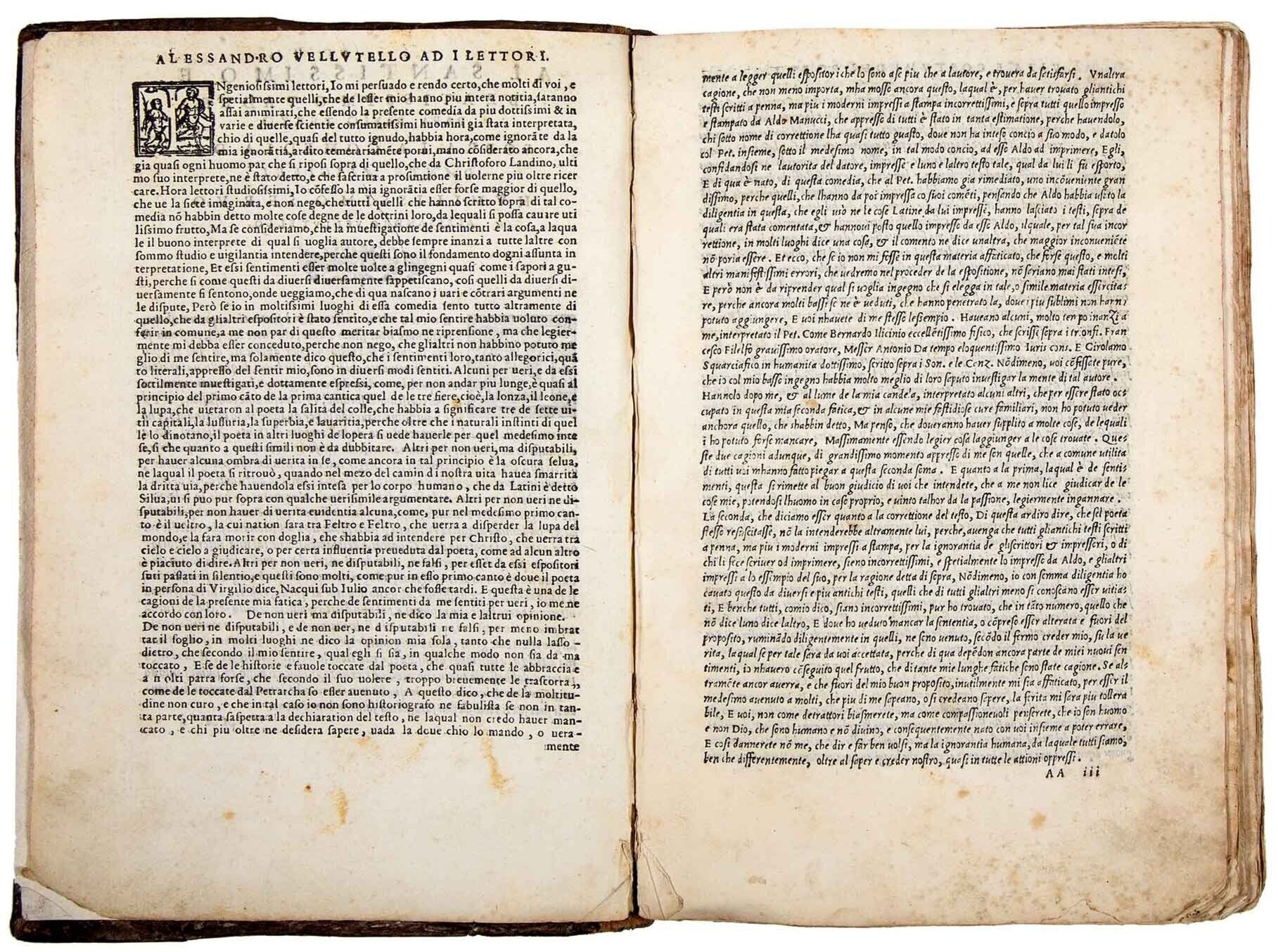

The story is, however, more intriguing, as Vellutello’s subsequent address to readers (‘ALESSANDRO VELLVTELLO AD I LETTORI’) clearly shows. Here a page newly set in a small Roman type and bearing an animated initial (fol. AA2v), appears opposite a page composed in the small italic, which is, however, different from that employed by Rampazetto for the preliminary letter to Paul III: in fact, it is the font used by Marcolini in 1544 (fol. AA3r).

Vellutello’s address to readers, from Rampazetto’s 1564 re-issue of Marcolini’s Commedia.

The mystery is amplified by the colophon printed on the recto of the penultimate leaf of the volume, which bears the name of Francesco Marcolini as the printer along with the original date of 1544.

The Rampazetto Commedia of 1564 is therefore not a mere reprint, but rather the result of a more unscrupulous initiative. It is the re-issue of Marcolini’s twenty-year-old edition, which Rampazetto put back on the market: printing a new title-page bearing his name and the new publication date, he packaged it together with the sheets composing the 1544 Commedia (which evidently had passed into his hands), replacing, as necessary, some leaves that were defective, and resetting other leaves that were lacking.

“Descrittione de lo Inferno” from Rampazetto’s re-issue of Marcolini’s Commedia.

The great importance of the copy offered here lies not only in its absolute rarity, being only the second known copy of this re-issue. In fact, the present copy represents the only recorded copy that is complete from a textual point of view: both the PrPh copy and the Notre Dame copy are lacking the last blank leaf, while the latter is also missing two leaves of text, BB1 and BB8, which are present in the PrPh copy.

Further, thanks to the kind collaboration of the Notre Dame library, we were able to compare both copies in great detail, including running titles, signature marks, and punctuation. In so doing we were able to unveil some variants between them, and to establish that the PrPh copy of the Commedia of 1564 contains additional leaves that were reset by Rampazetto. In the Notre Dame copy, the reset leaves are in fact detectable only in the first quire, while the present copy includes four more reset leaves, these being included in Paradise (fols. AY3-AY6).

It is also interesting to note that quire K of the PrPh copy contains the four central leaves misprinted by Marcolini himself, as they are in his 1544 type (K3v on the verso of K5r, K4v on the verso of K6r, and vice versa), and were therefore not reset by Rampazetto.

In 1995, the Notre Dame copy of the 1564 re-issue caught the attention of Brian Richardson, who mentioned the volume in his essay “Editing Dante’s Commedia, 1472-1629” (T. C. Cachey, ed., Dante Now. Current Trends in Dante Studies, Notre Dame 1995, pp. 237-262). As he writes:

It looks, though, as if Vellutello's first edition was not as successful as it might have been. In the rich John A. Zahm Dante collection at the University of Notre Dame is a reissue, unnoticed until recently, of the 1544 edition which was brought out in 1564 by the enterprising printer Francesco Rampazetto. Evidently several copies of the first edition had remained unsold, and Rampazetto decided to use the quite common trick of selling them as if they were new (p. 250).

Obviously, similar tricks are common not only in Venetian book production, but more generally in the history of printing, which is rich with clever instantiations of camouflage. Copies that had previously gone unsold were frequently put back on the market and presented as new with updated title-pages and other paratextual materials such as dedicatory letters or prefaces.

However, Richardson’s reasoning for the existence of these unsold copies is not entirely convincing given the success of the Marcolini Commedia. This is evinced not only by the high number of copies recorded worldwide, but also by the edition’s presence in the collections of the most distinguished Renaissance bibliophiles, as the PrPh copy once belonging Marcus Fugger well attests (see the complete description of this copy here).

In this regard, we offer an alternative explanation.

While the wealthy Sessas were able to purchase the fine cycle of woodblocks employed for illustrating the 1544 Commedia from Marcolini’s heirs, the more modest Rampazetto could only afford typographical material of minor value. At that time, he also came into possession of a stock of copies that had remained unsold, owing not to an alleged lack of commercial success, but rather to their defective condition or incompleteness.

The Sessas’ publishing initiative of 1564, i.e., the printing of the ‘Nasone’ Commedia, edited by Sansovino and illustrated with the woodcuts executed for Marcolini in 1544, stimulated Rampazetto to profit from the favorable occasion by simultaneously putting ‘his Dante’ on the market, assembling in various ways the defective or incomplete material that was now in his hands. Assembling the sheets, he attempted to package, as far as possible, complete and ‘acceptable’ copies for his clientele, resetting the leaves that were in too poor condition or even lacking in the stock he had acquired. This could explain the fact that our copy contains more leaves reset by Rampazetto, as well as leaves misprinted by Marcolini, than in the Notre Dame copy, suggesting that each copy of the 1564 re-issue was a sort of ‘unique piece’, labouriously re-assembled with increasing difficulty.

An entirely different matter is the variant in Canto II of Purgatory (fol. V7r), which is visible in this copy as well as in the copy at Notre Dame: a terzina (vv 64-66) was omitted on this leaf as issued during the first print run in Marcolini’s press. The mistake was noticed by Marcolini and his collaborators and, as the 63rd line came at the bottom of the page, it was possible to add in the omitted lines via hand-printing, with different spacing and in darker ink. A few copies without this addition are however also recorded.

This hand-printed terzina is added in the present copy as well as in the copy at Notre Dame.

We have examined various copies of the 1544 Commedia. Curiously, these added lines are recorded in two slightly different variants, showing the letter ‘u’ for the ‘v’ and the letter ‘e’ for the ligature ‘&t’, a typographical oddity which perhaps reveals a temporal gap between the two different forms.

The terzina added at the bottom of the leaf in this copy and in that of Notre Dame shows precisely this use of ‘u’ for ‘v’ and ‘e’ for the ligature ‘&’, and the lines are set in a type very similar but not identical to the italic fonts employed in 1544, as further attested in some copies of the Marcolini Commedia (we reference to the copy kept at the Casanatense Library in Rome, http://opac.casanatense.it/Record.htm?idlist=1&record=19073617124918918999).

In the present copy of the Rampazetto re-issue, the impression of these added lines is grey and blurry.

Can this poor printing be read as further testimony of the defective condition of the unsold stock acquired by Rampazetto? Was the terzina, in this variant form, added in the present copy in the Marcolini press, perhaps in a subsequent phase? Or is it even possible to suggest that this addition was made, twenty years later, in the shop run by Rampazetto in calle delle Rasse? Is it possible that copies recorded as ‘Marcolini copies’, but often incomplete, could indeed hide interventions by the enterprising Rampazetto?

We have no sufficient typographical evidence, and the scarcity of the surviving copies of the Rampazetto Dante does not allow for an unequivocable answer to these questions, but the matter deserves further research. One point is however clear: the study of re-issues is always of great interest, providing insight into unscrupulous but common commercial strategies, and ‘materially’ revealing unknown, curious, and mysterious circumstances or ‘accidents’ in the printing history.

How to cite this information

Margherita Palumbo, “An Extraordinarily Rare Book: The 1564 Rampazetto Re-Issue of Marcolini’s Commedia” PRPH Books, 22 April 2020, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/rampazetto. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

![Title page of Dante Alighieri’s La Comedia di Dante Alighieri con la nova esposizione di Alessandro Vellutello.... Venice, Francesco Rampazetto, 1564 [at the end: Francesco Marcolini for Alessandro Vellutello, 1544].See the complete description of t…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1587588031363-11NC1GET8FL65FA33BR1/Rampazetto-title-page.jpg)