PR & PH at Firsts Italia

From 19 to 22 May, Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco and Philobiblon will be exhibiting at FIRSTS ITALIA, the online rare book fair organized by the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association (ABA) in partnership with Associazione Librai Antiquari d'Italia (ALAI). The first FIRSTS ITALIA was held in 2021, as part of the ABA’s ‘Firsts Online’ series created during the pandemic as an alternative to in-person events. It returns this year by popular demand, featuring hundreds of antique, rare, curious and interesting works chosen specifically for the occasion.

We feature here just two works each from the fabulous selections to be showcased by Libreria Antiquaria Pregliasco (at stand 32; get the catalogue here) and Philobiblon (at stand 45), starting tomorrow.

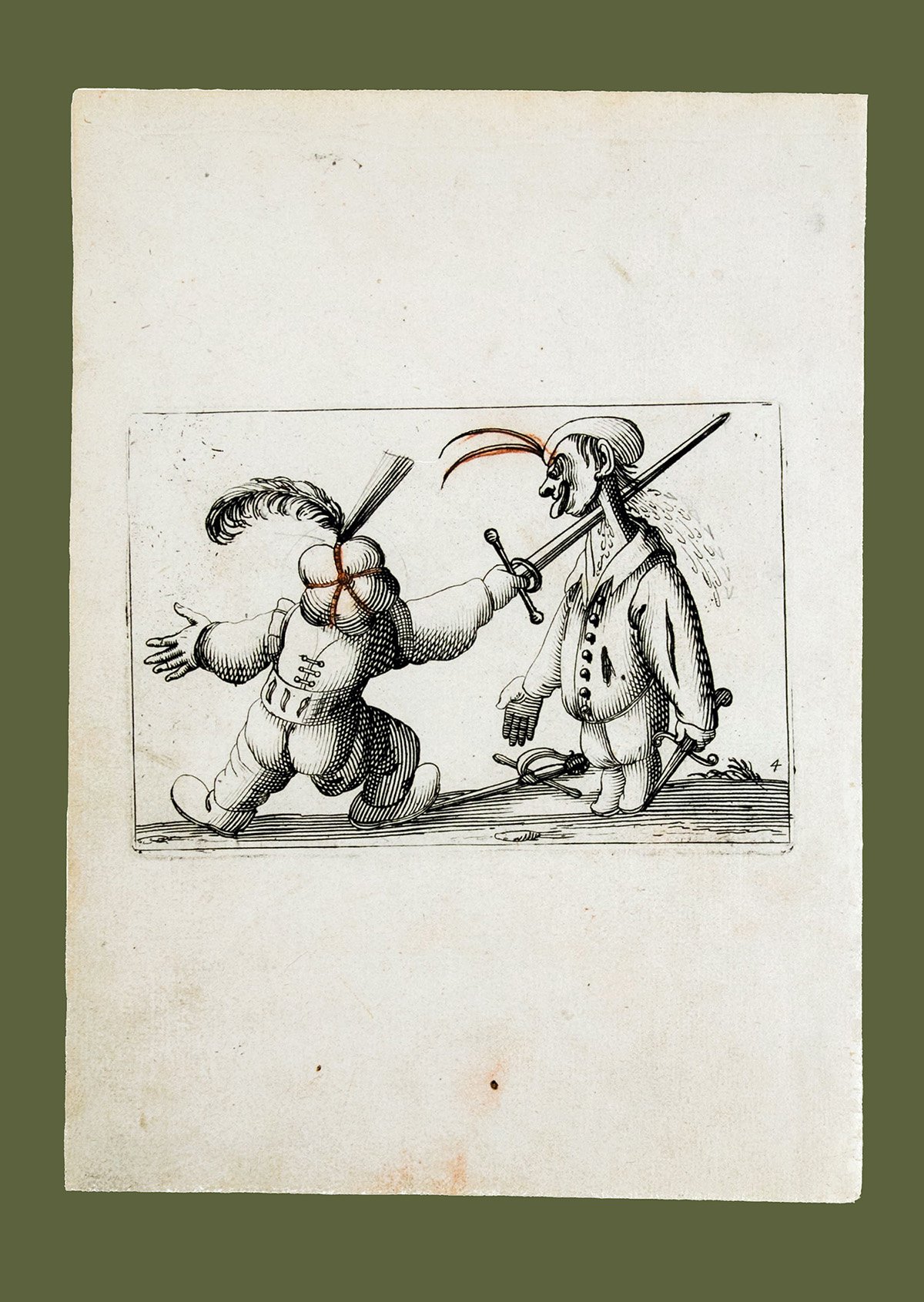

Lucini, Antonio Francesco (1605/10-1661). Compendio dell’Armi de’ Caramogi D’Ant. Fran. Lucini. In Firenze An. M.D.C.XXVII. F.L.D. Ciartres excud. (1627).

Series of 23 etchings and engravings (out of 25, lacking plates nos. 13 and 24). Each 78-81x117-120mm, on contemporary laid paper with watermark of a shield with heraldic arms. Loose sheets with very large margins of 7-8cm at both top and bottom and over a centimetre at both sides. In an elegant contemporary album with 48 leaves: each plate is preserved between two leaves, the upper leaf having a window through which the plate is seen.

€ 30.000

An extremely rare set of 23 of (25) numbered etchings, including title, by the little known italian artist Antonio Francesco Lucini (or Luccini), active in Florence and Nancy in the first half of the seventeenth century. Lucini’s art is very close to that of Callot, Della Bella and Baccio del Bianco. The 23 prints (n. 13 and 24 are lacking) are fanciful, bizarre, and highly original engravings, with a variety of scenes with one or two clumsy characters (Caramogi) mostly fencing, wielding various types of light and heavy weapons (from daggers and swords to pikes and even cannons). This series, apparently never seen on the market, is only described by F. Viatte in “Master Drawings” vol. XV (1977), where it is fully reproduced, and in an article on Baccio del Bianco, in Parody and Festivity in Early Modern Art, Ashgate 2012.

This extraordinary suite of dwarfs dueling with arms or carrying other weapons is a satire of macabre seventeenth-century entertainment featuring a combination of bizarre costuming and grotesque violence. As an independent genre Florentine caricature becomes more common in the early seventeenth century: one thinks of the depictions of hunchbacks (Gobbi) by such artists as, Valerio Spada, Stefano and Callot, with whom Lucini is often associated. (Viatte discusses a significant number of drawings of dwarfs by Stefano.) If it was ever more widespread, the survival rate of such engraved suites is tenuous indeed, whether because they are so anti-thetical to the main currents of Florentine art, or because of its hypothetically “popular” character notwithst-nding some of the stellar names associated with it. One could well imagine that the pleasure they offered was ephemeral, and that they only began to be collected by the encyclopedic collectors of the 18th c. and onwards.

Lucini is said to have been a pupil or otherwise in the circle of Callot, first in Florence (1616), and subsequently in Nancy. He is known for engraving after della Bella, for a retrospective suite (?) of engravings on the siege of Malta (Disegni della Guerra), and best known for engraving the great sea atlas Arcano del Mare (1645-6).

The suite is published (excudit) by the Parisian publisher and sometime engraver Francois L(')anglois. This appears on the title, none of the other plates is signed. Accordingly, “in Firenze An MDCXXVII” is not publication information, and the most likely place of publication is Paris. We note that Langlois published at least one title by Callot (Lux Claustri 1646), and perhaps that is the connection. We have located two copies: the BN copy reproduced in its entirety by Viatte in her MD article-- an excellent indication of the suite's rarity; and a copy listed in ICCU, Vicenza, at the Biblioteca Civica Bertoliana (lacking 1 plate?) We find no record of the present suite in either the Metropolitan collection data base (which lists under Luccini an anonymous army of dwarfs, presumably engraved by Luccini), and a print of the bridge at Pisa after della Bella; or the BM on-line site, which lists a single print after della Bella.

F. Viatte, “Allegorical and Burlesque Subjects by Stefano della Bella”, Master Drawings, 15 (1977). pp. 347- 365; S. Cheng, “Parodies of Life: Baccio del Bianco’s comic drawings of dwarfs”, D. R. Smith (ed.), Parody and Festivity in Early Modern Art. Essays on Comedy as Social Vision, Farnham 2012, pp. 127-142.

The first statement of Fermat’s celebrated 'Last Theorem',

which he didn’t prove because "Hanc marginis exiguitas non caperet"

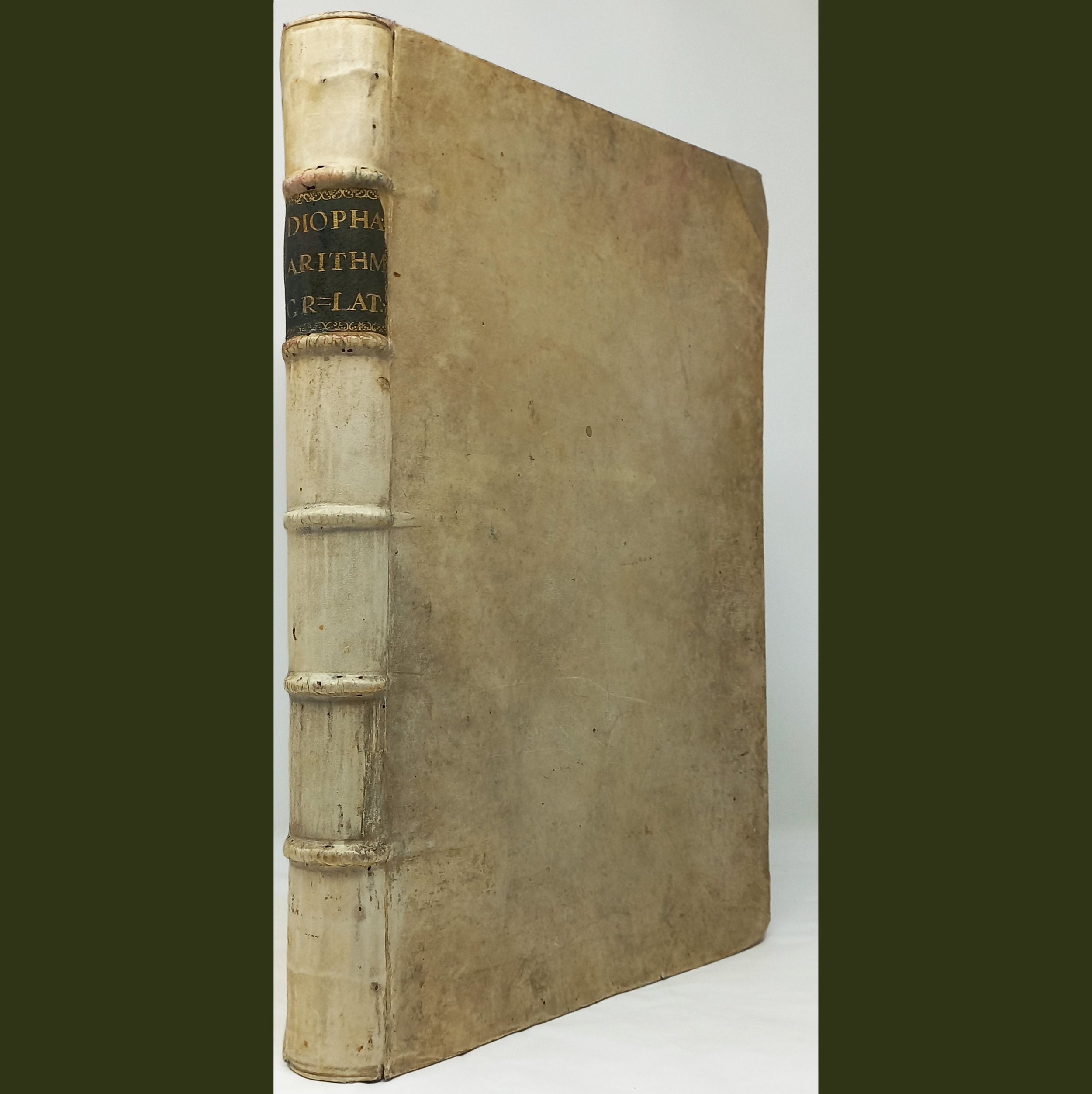

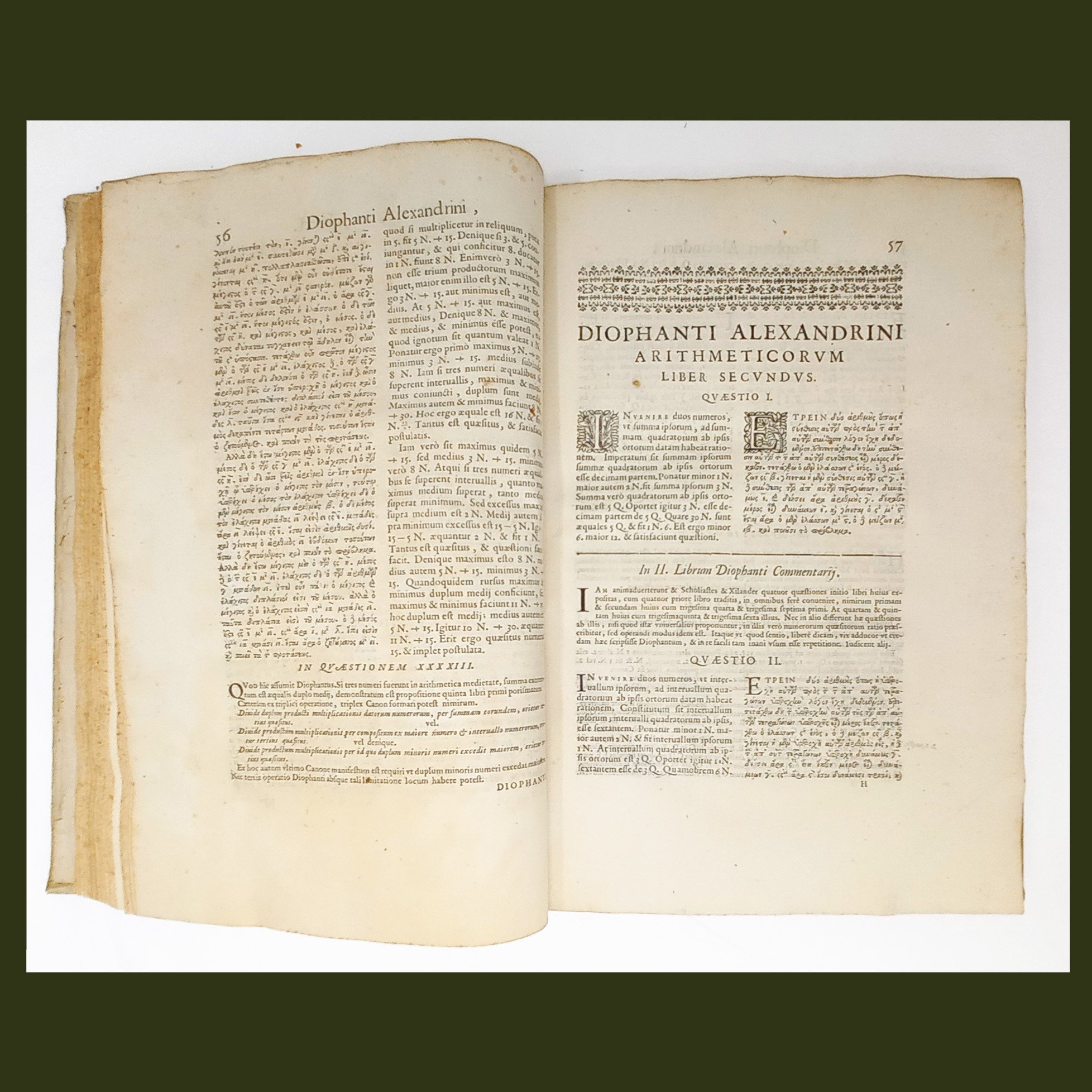

Diophantus, Alexandrinus (ca. 200/214 AD - ca. 284/298 AD). Arithmeticorum libri sex, et De numeris multangulis liber unus. Cum commentariis C. G. Bacheti V. C. & obseruationibus D. P. de Fermat. Tolosae, Bernardus Bosc, 1670.

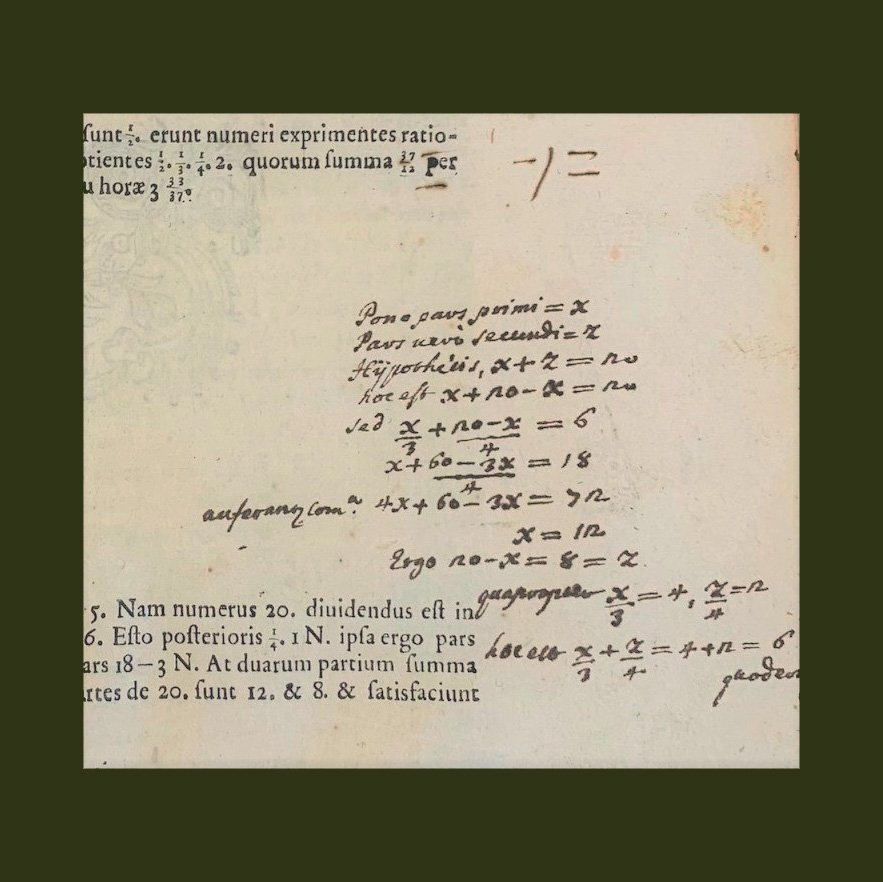

Folio (350x230 mm), [12], 64, 341, (1); 48 pp. Contemporary vellum green title label on spine. Greek and Latin text in parallel columns, Latin commentary in a single column. Engraved title vignette after Rabault, two engraved headpieces, engraved opening initial, woodcut initials and ornaments. Edited by Claude Bachet de Méziriac (1581-1638), commentary by Pierre de Fermat (1601-1665). A good copy on thick paper, partial loss to the label, restorations to one corner and to a portion of the back joint, the right margin of the title-page with light foxing and small wormholes, a few leaves with spotting and foxing, a light water stain towards the sewing in the first ten leaves. Lacking the errata leaf as in most known copies. An interesting note in ink in the margin of p. 279.

€ 38.000

First edition of Fermat's annotated edition of Diophantus’ Arithmetica, and the first printing of Fermat's contributions to the theory of numbers.

Fermat owned a copy of the Greek editio princeps of 1621 and wrote notes on the mathematical problems posed by Diophantus; he died without any intention of having them published. When his son Claude-Samuel chose to include the annotations in this second printing of the work, he presented the first contribution by a Renaissance mathematician to the theory of numbers and the first step in the invention of differential calculus. The most famous of the 48 observations made by Fermat appears on p. H3r: the first statement of his celebrated 'Last Theorem', not proven until 1995 when Princeton professor Andrew Wiles completed a 130-page proof. Fermat had claimed he knew the proof but lacked the space in the margin to show it ("Hanc marginis exiguitas non caperet”).

Honeyman 893; Norman 777. DSB, IV, 573. Smith, Rara Arithmetica, p. 348.

Writing women at their desks

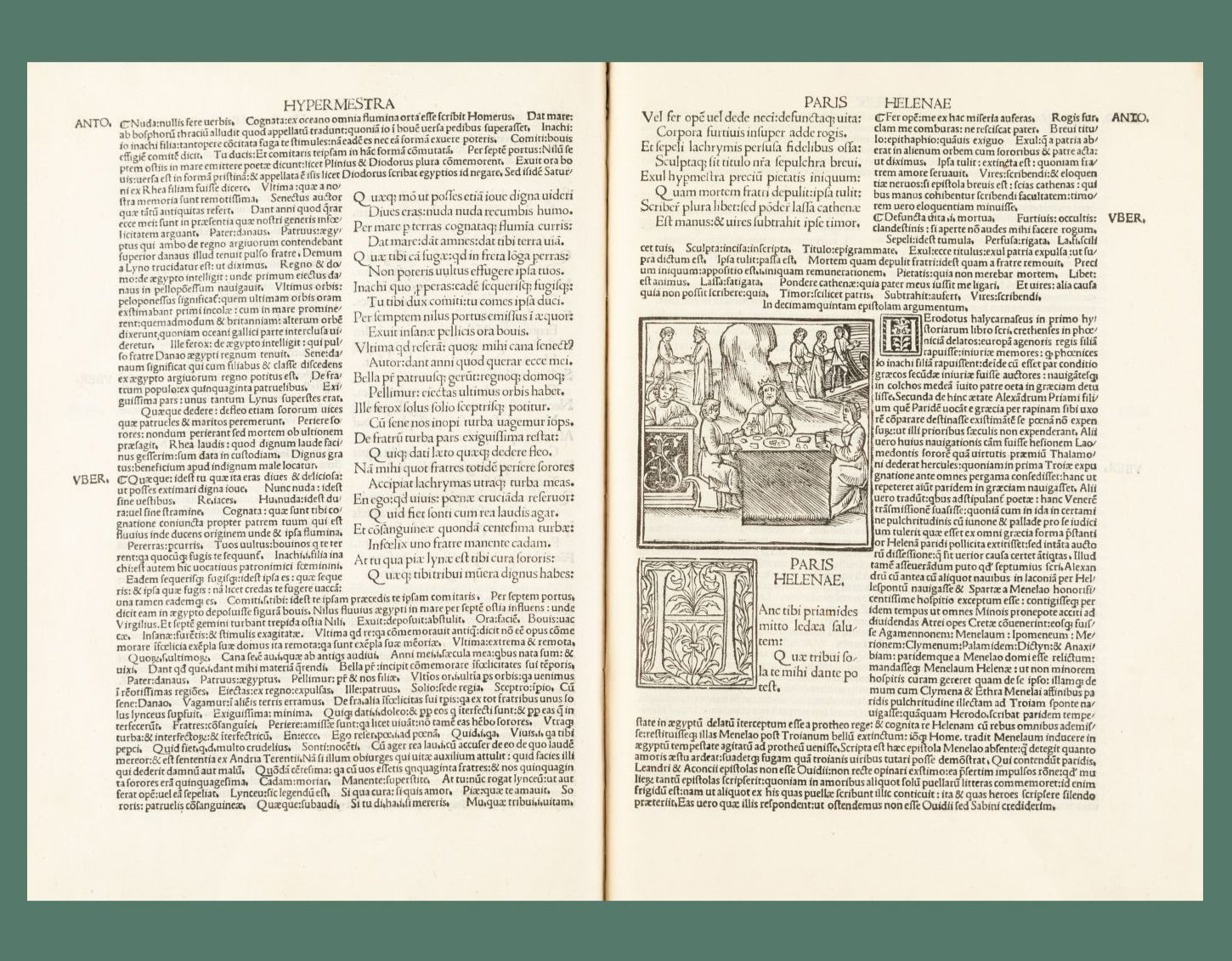

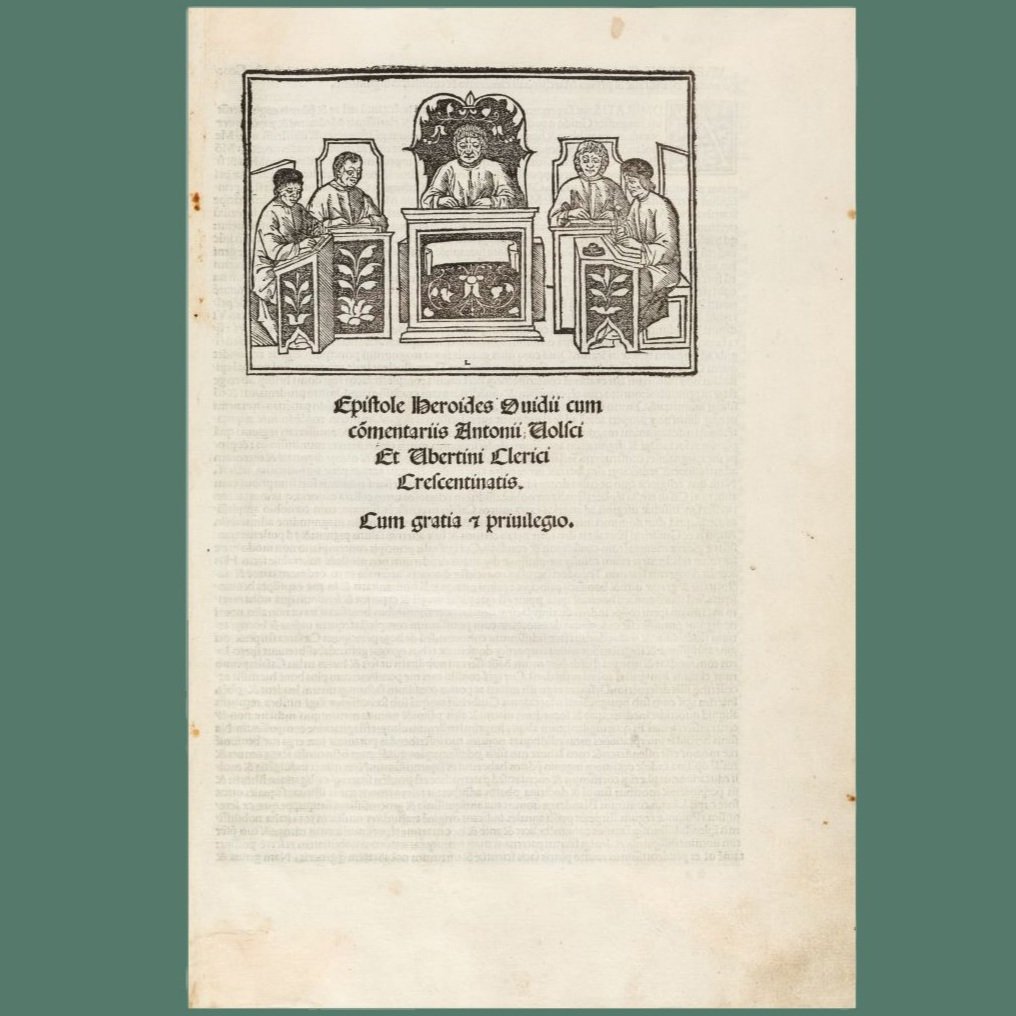

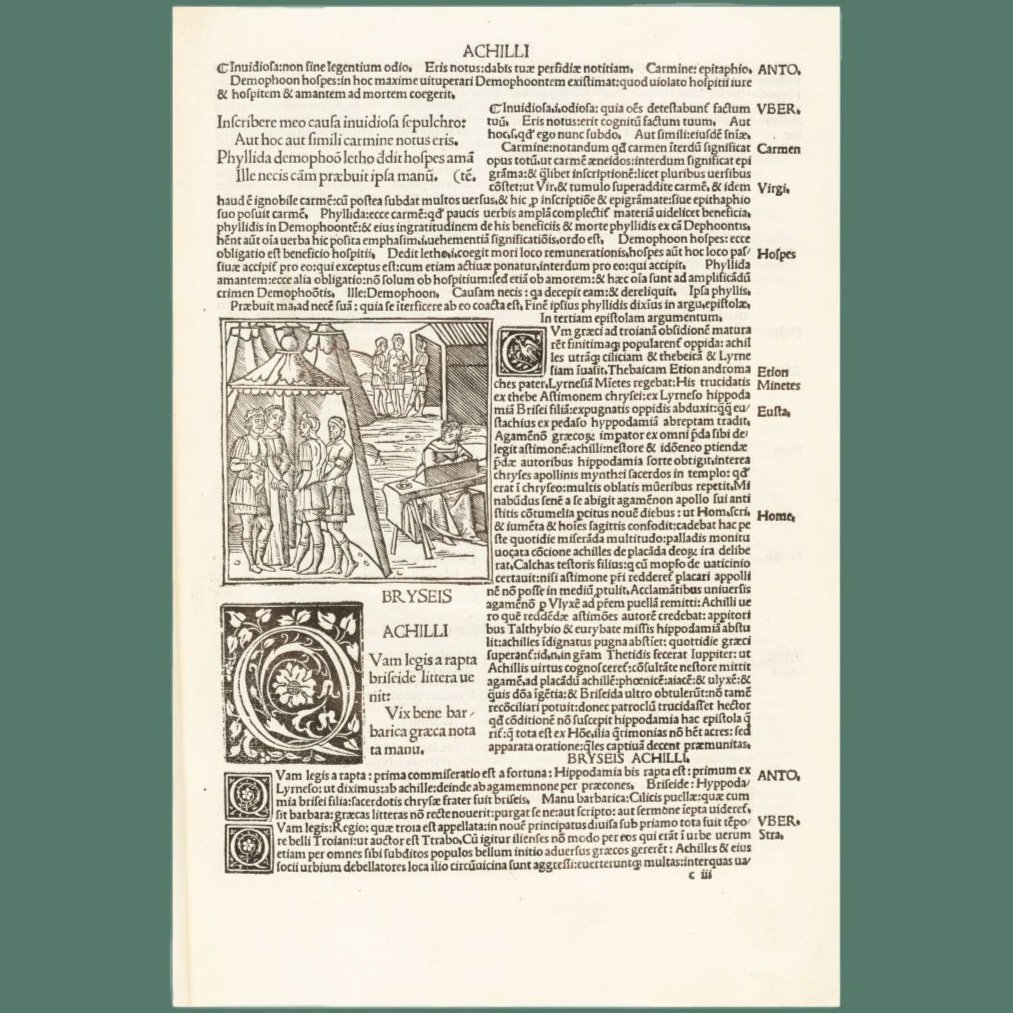

Ovidius Naso, Publius (43 BCE-17/18 CE). Epistole Heroides Ouidii cum com[m]netariis Antonii Volsci Et Ubertini Clerici Crescentinatis. Cum gratia et privilegio. Venice, Bartolomeo Zani, 20 December 1507.

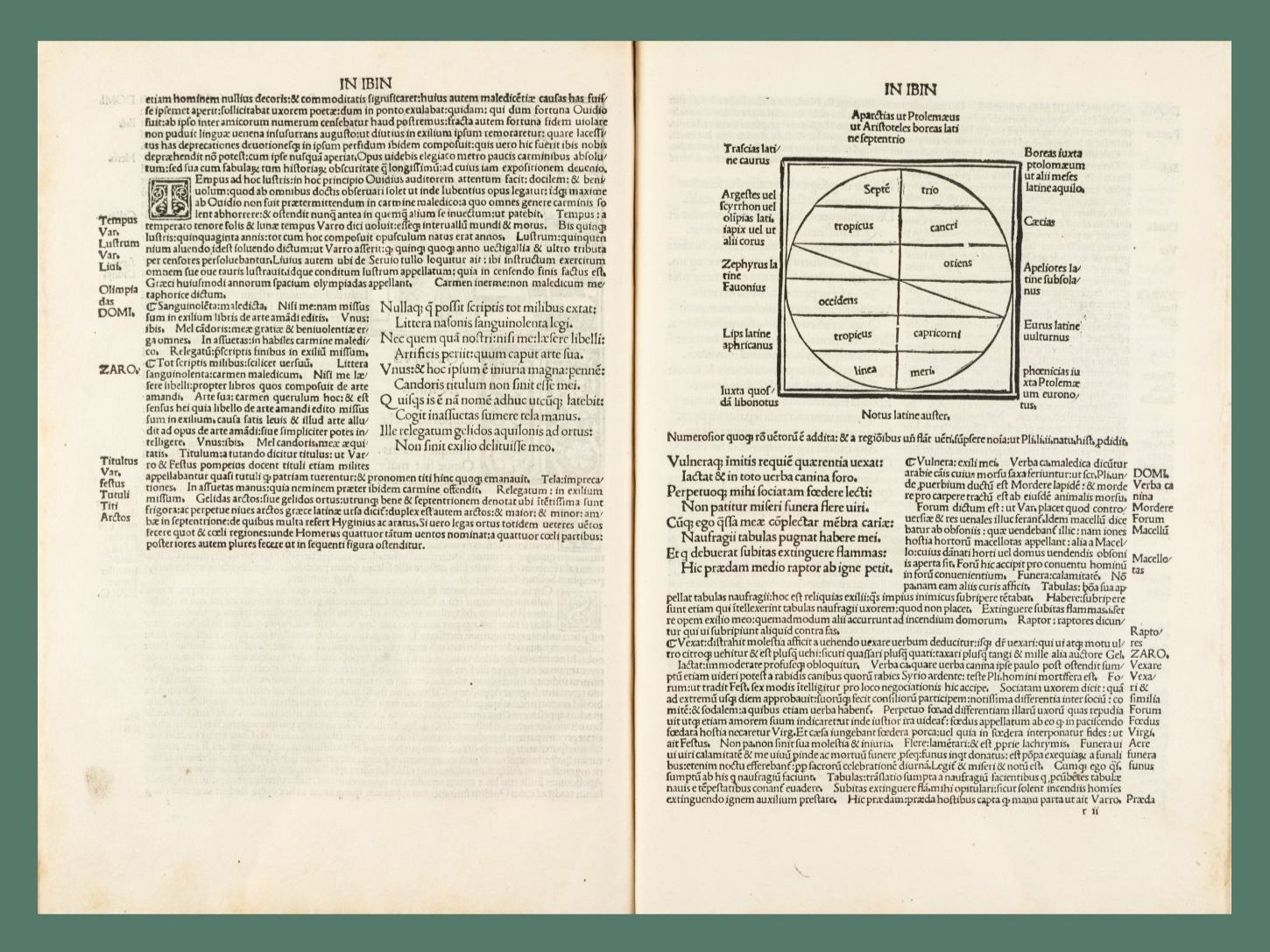

Folio (311x208 mm). Collation: a-t6, u8. [122] leaves. Roman and Greek type. Woodcut printer’s device on black ground on the recto of fol. u8. Large woodcut vignette (92x137 mm) on fol. a1r, signed ‘L’; text illustrated with a series of 23 woodcut vignettes (ca. 81x81 mm) illustrating each letter, and the final invective In Ibin (the diagram with labels set in type on fol. r2r is counted in the 23 vignettes). The vignette on fol. a3r is likewise signed ‘L’ and framed within an elaborate trophy border, with a dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit inserted at the top, and a blank shield at the foot. Woodcut initials in three different sizes, many on black ground. Eighteenth-century half-marbled leather. Smooth spine, title in gold on hezelnut morocco lettering-piece. A very good, wide-margined copy, first and last leaves slightly toned, a few tiny wormholes at the beginning and end, without any loss.

$6,000

Rare Venetian illustrated edition of this famous collection of twenty-one imaginary letters belonging to Ovid’s amatory works. The epistles, composed in elegiac couplets, were transmitted as a corpus in the manuscript tradition, receiving the title of Heroides or Epistolae heroidum. Together with the Metamorphoses, the Heroides represents Ovid’s most influential work, highly appreciated for its moving narrative. Its fortune in the Renaissance was especially remarkable: numerous editions – supplemented with Ovid’s invective in verse against a personage called Ibin – followed its first appearance in 1471, accompanied by an increasing number of commentaries.

The letters give voice to legendary women abandoned by their lovers or husbands, providing a model for the love-letter novel: counting among Ovid’s heroines are Penelope, Phaedra, Dido, Deianira, Ariadne, Medea, Helen, Hero, and Sappho. The fictional epistolary frame is further ensured by the presence of six double-letters, wherein the recipient responds to the original sender. These occur between Paris and Helen, Leander and Hero, and Acontius and Cydippe.

The epistolary frame was well recognized in sixteenth-century illustrated editions of the Heroides. While incunable editions limited the illustration to a single woodcut portraying an author among his commentators or disciples, a new template was introduced by the Venetian Johannes Tacuino in the Heroides of 1501, in which each epistle opens with a vignette – divided into three compartments – depicting salient episodes in the story.

For his previous Heroides of 1506, Bartolomeo Zani – who was born in Portese, near Brescia (Lombardy), and was active in Venice as of 1487 – proposed a different illustrative set, eliminating the three-compartment layout. The first, and larger woodcut, depicting the author among his disciples, is however still faithful to the fifteenth-century tradition, and had previously been used for the Horatius issued in 1505 by the Venetian Filippo Pinci, thus confirming the close collaboration between the two printers. This vignette is signed ‘L’, and the same letter is visible in the next and narrower woodcut, introducing Penelope’s letter to Ulysses, framed in a fine border first employed in the Ragazzo-Giunta Italian Bible of 1492, and re-used in 1502 – with a few differences – by Zani for his edition of Livius’s Deche. The letter ‘L’ is one of the monograms attributed by Essling to the itinerant woodcutter and printmaker Lucantonio degli Uberti (fl. ca. 1490-1550, active in Verona, Venice, Florence, and even Hungary, and well known for having created woodblocks on behalf of Titian, including a nine-block woodcut made in 1512/13 after the Triumph of Faith, frescoed in 1511 for the Scuola del Santo in Padua.

However, Zani’s Heroides of 1507, presented here, is not a mere reprint of his 1506 edition. The reading of Ovid’s text is now facilitated by a considerably increased number of shoulder notes, as well as an illustrative apparatus of significant novelty. In 1506, the 21 letters and the final Ad Ibin are in fact illustrated with 23 vignettes from 22 woodblocks, with the same block used for both Sappho’s letter to Phaon and the invective to Ibin. In 1507, a new woodblock was made for illustrating the story of Sappho and Phaon, thus correcting the visual incongruence. The 1507 edition therefore offers the definitive and complete state of the Zani cycle for the Heroides.

It is highly remarkable that in both the Tacuino set and in the Zani set the heroines are mainly depicted at their desks and in the act of writing, a template later employed in manuscripts addressed to women, or in editions of works composed by female authors.

Mortimer Italian 334; Sander 5268; Essling 1139; Rava, p. 27; M. Fadini – L. Gambuzzi, “’Nessuno ardisca imprimere’? Filippo Pinzi tra coedizioni e intrecci di privilegi di stampa nella Venezia del primo Cinquecento”, La Bibliofilia, 120 (2018), pp. 27-64; G. Patellani, “Lucantonio degli Uberti”, Print Collector, 9 (1974), pp. 6-15.

The New Patronage

Depero, Fortunato (1892-1960). Saggio futurista 1932. Numero unico redatto dal pittore poeta Fortunato Depero in occasione della venuta nel Trentino di S. E. Marinetti. Rovereto, Tipografia Mercurio, 1932.

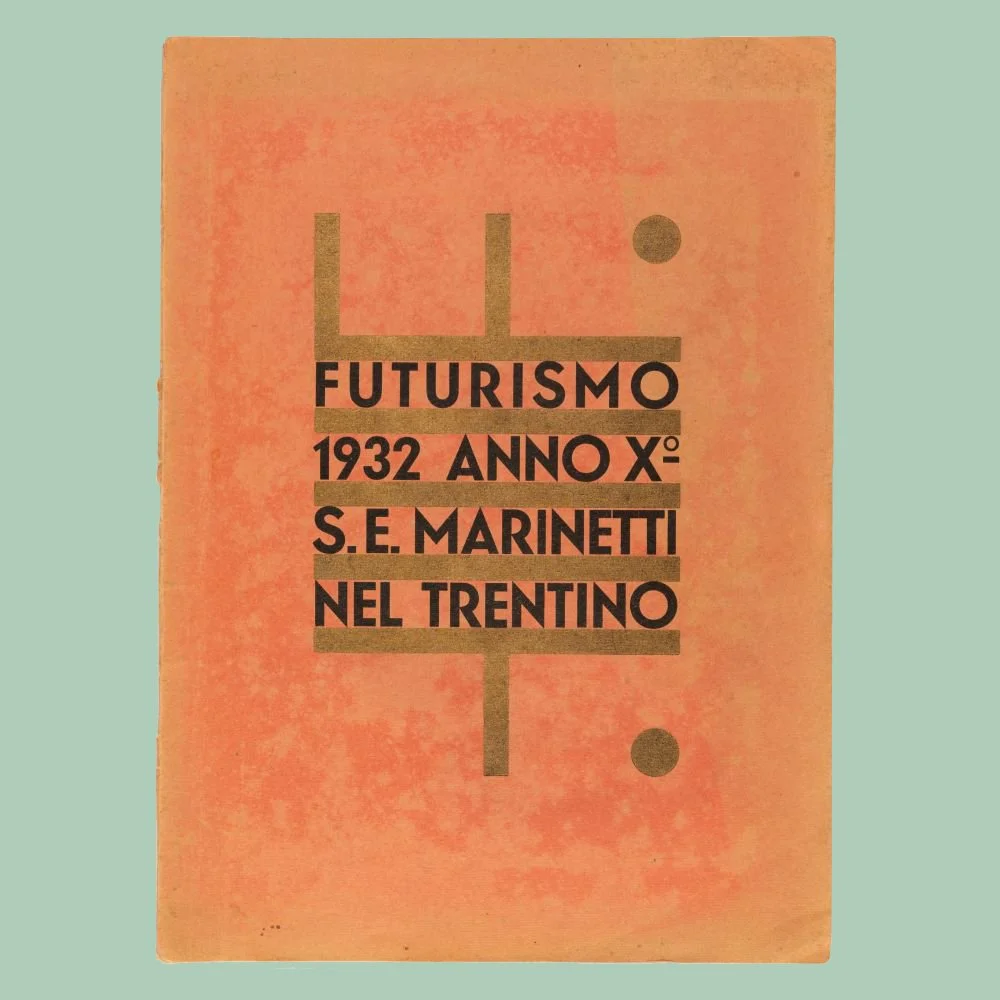

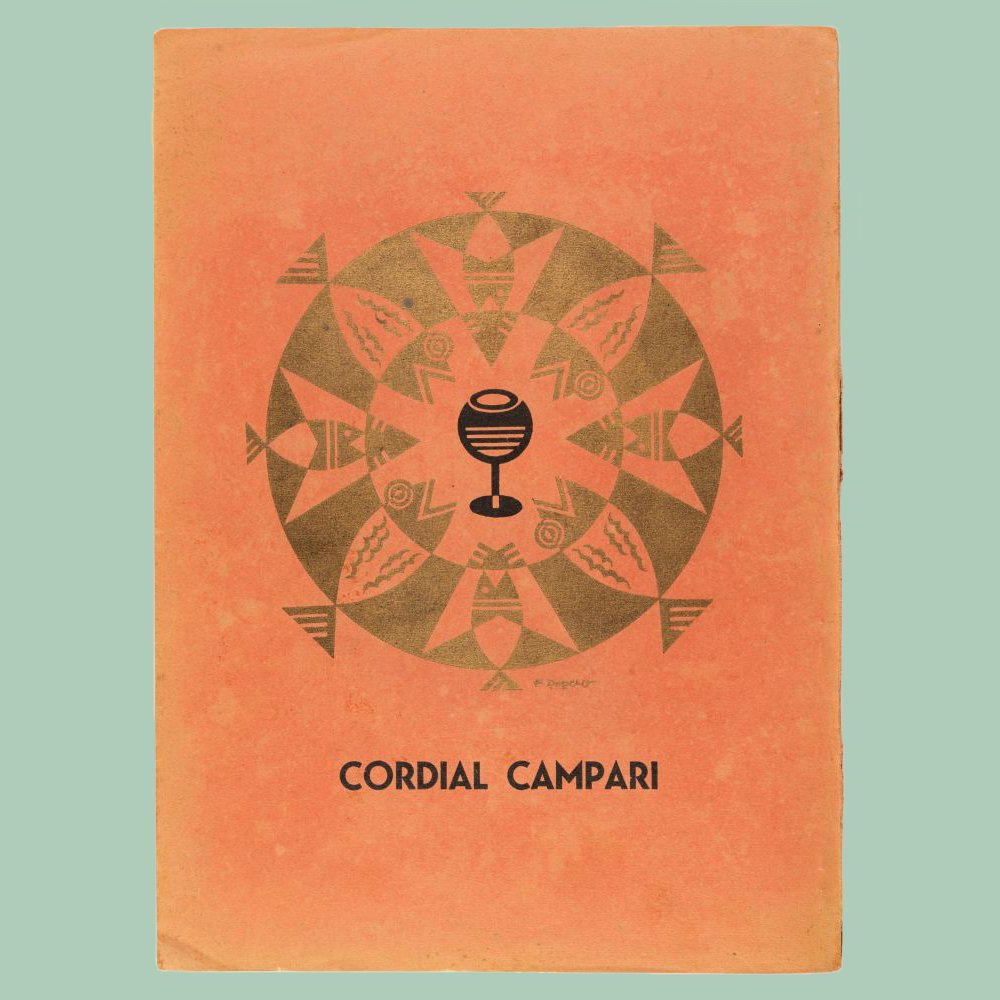

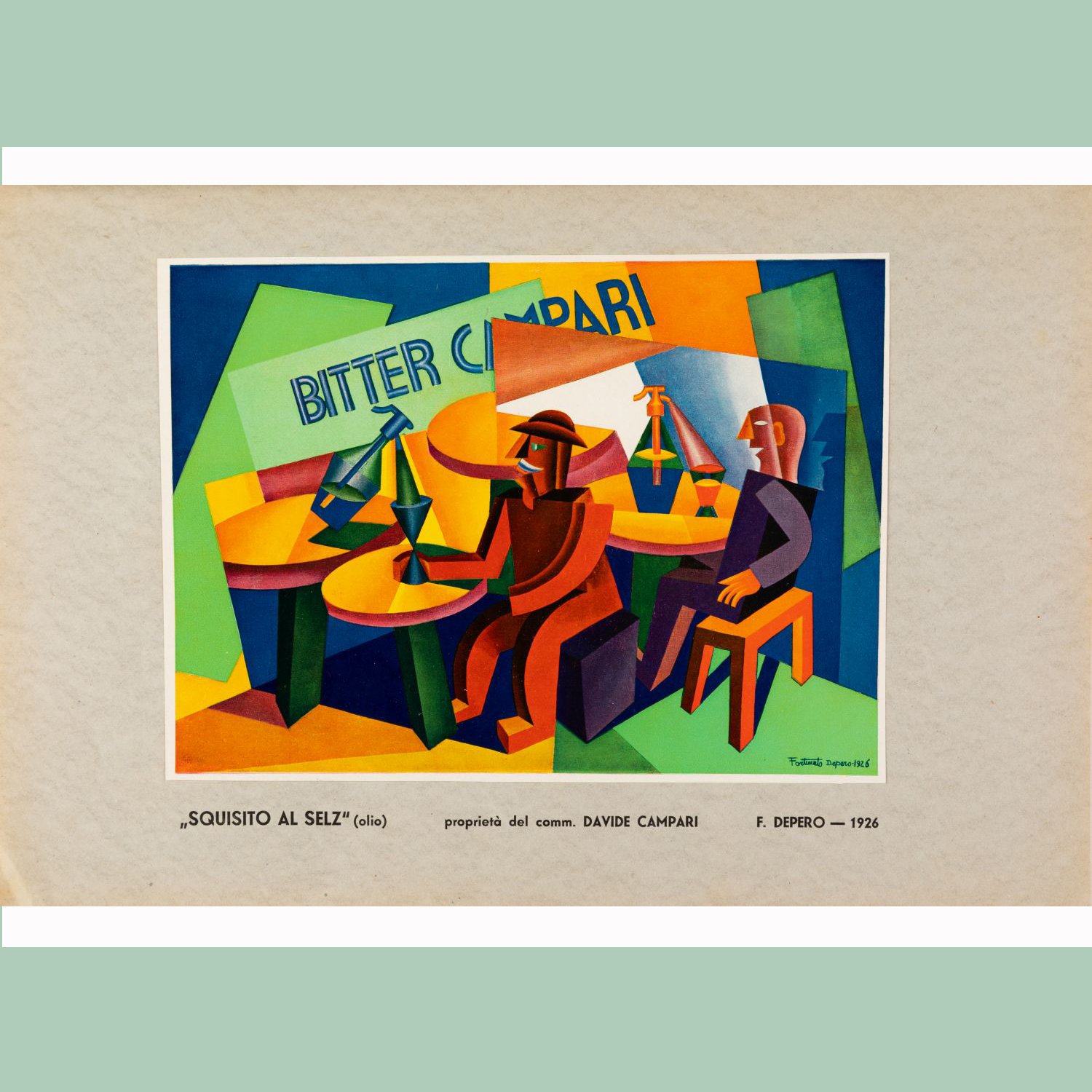

Folio (245x340 mm). [16] leaves, of which three are printed on glossy paper, and the last three on yellow paper, including advertisements of companies and shops located in Rovereto. Marinetti’s halftone photographic portrait, printed on glossy paper, and protected by tissue paper; two colour plates, both protected by tissue paper: ‘Mucca in montagna, Arazzo di Depero’ (1926), and ‘squisito al selz’ (1926), the latter mounted on cardboard. Eight monochrome plates. Illustrations and parolibere in text. Publisher’s original salmon-pink wrappers printed in black and gold. On the upper cover, four-line title written in black between five gilt lines, the first and last of which extend to form, respectively, the letters ‘F’ (referring to ‘Futurismo’ as well as to ‘Filippo’, i.e. Marinetti’s first name) and ‘T’ (referring to ‘Trentino’ as well as to ‘Tommaso’, i.e. Marinetti’s second name). On the lower cover, an advertisement for ‘cordial campari’, printed in black and gilt, and signed by Depero. Light fading to the upper cover, minor loss to spine. A very good copy, corners slightly bumped.

Provenance: Dedication copy to Arturo Benvenuto Ottolenghi (1887-1951; Fortunato Depero’s autograph address on the title-page (‘Sempre ed immutabilmente ad Arturo Benvenuto Ottolenghi Fortunato Depero Rovereto 18 aprile 1932’; Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s address ‘a Arturo Benvenuto Ottolenghi con simpatia futurista T.T. Marinetti’, penned at the margins of his photographic portrait.

$3,700

First edition of this ‘numero unico’ or unique issue, one of the best examples of Depero’s highly innovative and influential graphic design, published on the occasion of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s visit to Depero’s hometown of Rovereto.

The publication gathers texts and parolibere, or words-in-freedom, composed not only by Depero, but also by Marinetti and other Futurists, including the Battaglia di via Mercanti – written by Marinetti after the anti-socialist ‘battle’ instigated by Mussolini’s followers in Milan in April 1919 – and the manifesto L’Aeropittura futurista, written in 1929 by, among others, Marinetti, Giacomo Balla (1871-1958), Enrico Prampolini (1894-1956), and Depero himself.

The present copy is an example of the rarer and more sought-after issue of the publication, with pink wrappers and an illustrated advertisement for Cordial Campari printed in gilt and black on the lower cover. Indeed, the Milan-based liquor company was partially responsible for sponsoring the publication of the Saggio futurista 1932.

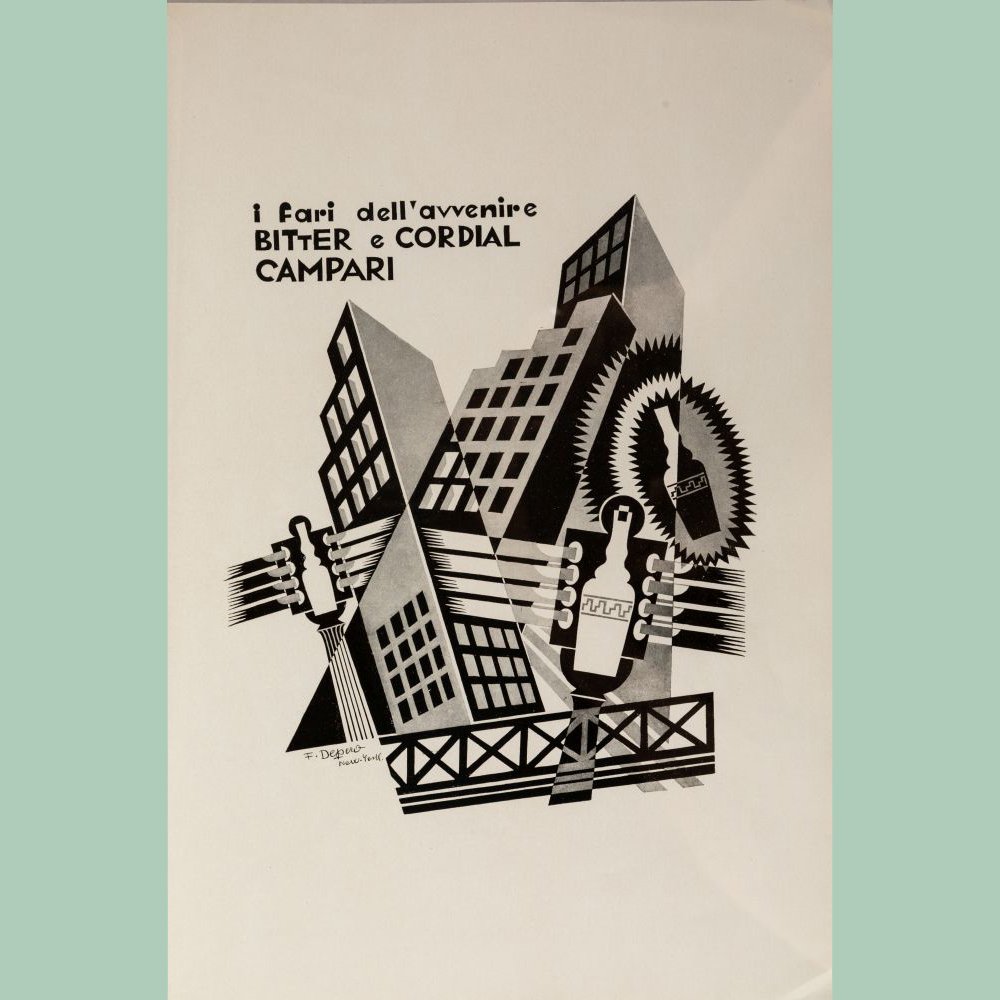

Depero officially began collaborating with Campari in 1927, after having painted, for the xv Venice Biennale of 1926, the Squisito al Selz advertisement, iconic in its parolibere-inspired lettering, broken lines, and strong colouring. Its reproduction is included in the Saggio futurista 1932, along with other Campari advertisments printed in black and white.

In 1931, Campari commissioned the Numero unico futurista Campari, containing Depero’s Il futurismo e l’arte pubblicitaria, a revolutionary manifesto in which the artist breaks down the divide between ‘high art’ and advertising and envisages companies as heirs of great Renaissance patronage. The copy presented here is itself a testament to this new form of patronage, in that Depero gave it as a gift to his own great patron, the entrepreneur and art collector Arturo Benvenuto Ottolenghi. Ottolenghi and his wife Herta von Wedekind zu Horst (1885-1953) had transformed their residence at Acqui Terme, in Monferrato (Piedmont), into a center for artists, and Depero himself was invited to work at the villa. Ottolenghi was also the main sponsor of Depero’s first trip to New York in 1928 – a journey visually and textually documented in the Saggio futurista 1932 and made possible thanks to the ‘10.000 lire’ gifted by his generous patron. Hence Depero’s grateful dedication to Ottolenghi on the title-page of this copy: ‘sempre e immutabilmente’, ‘always and unalterably’.

D. Cammarota, Futurismo. Bibliografia di 500 scrittori italiani, Milano, 2006, 169.5; C. Salaris, Riviste futuriste. Collezione Echaurren, Pistoia 2012, p. 274; C. Salaris, Il futurismo e la pubblicità: dalla pubblicità dell’arte all’arte della pubblicità, Milano 1986, pp. 130–131; G. Bianchi, “1926: la prima volta dei Futuristi alla Biennale; strategie e retroscena della marcia su Venezia”, Venezia arti, 17/18. 2003/04 (2006), pp. 119-134; M. Mojana, Depero con Campari. Galleria Campari, 18 marzo – 18 giugno 2010, Roma 2010; R. Bedarida, “Bombs Against the Skyscrapers. Depero’s Strange Love Affair with New York 1928-1949”, International Yearbook of Futurism Studies, 6 (2016), pp. 43-70; R. Cremoncini, The Art of Campari, Cinisello Balsamo, Milano 2018; G. Ginex, Not Just Campari! Depero and Advertising, in Fortunato Depero, “Italian Modern Art” (monographic issue), 1 (January 2019), https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/depero/; F. Fontana et al., Villa Ottolenghi Wedekind. Una residenza del Novecento ad Acqui Terme, Torino 2015.