Giuseppe Zocchi and Il Calcio Fiorentino

Giuseppe Zocchi’s Veduta della Chiesa, e Piazza di S. Croce con La Festa del Calcio fatta L’anno 1738 alla Real presenza de Regnanti Sovranti is a masterful ode to the artist’s native Florence at a moment of transition in the city’s history. The final plate of his Scelta di XXIV Vedute delle principali contrade, piazze, chiese, e palazzi della Città di Firenze, published in 1744 from the presses of Giuseppe Allegrini, it shows the piazza with its halo of architecture from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries setting the stage for a game of calcio fiorentino, while in the foreground a host of carnivalesque characters flood the page: a snapshot of pageantry, debauchery, and an early instantiation of “the beautiful game”.

Giuseppe Zocchi (1711/6-1767), Pl. XXIV. Veduta della Chiesa, e Piazza di S. Croce con La Festa del Calcio fatta L’anno 1738 alla Real presenza de Regnanti Sovranti (View of the church and piazza of Santa Croce on the occasion of the festival of Calcio in 1738 in the royal presence of sovereign kings) from Scelta di XXIV Vedute delle principali contrade, piazze, chiese, e palazzi della Città di Firenze. Giuseppe Allegrini, 1744.

The Scelta di XXIV Vedute delle principali contrade, piazze, chiese, e palazzi della Città di Firenze was one of two sets of views by the artist to appear in 1744, both commissioned by the Florentine aristocrat Marchese Andrea Gerini (1691-1766), the other being Vedute delle ville e d’altri luoghi della Toscana, a series of 50 views of villas just outside the city.

Following the end of Medici rule in 1737, Francis Stephen, Duke of Lorraine, assumed the Regency of Tuscany, although he and his wife Maria Theresa of Austria, Queen of Bohemia and Hungary, visited only once, from 20 January to 20 April 1739, providing the occasion for the celebrated Calcio captured in Zocchi’s veduta. In their absence, a Regency Council was created which passed certain administrative measures that ultimately led to vacancies in the villas surrounding the city: as Richard Harprath has persuasively argued, the Vedute delle ville e d’altri luoghi della Toscana may have been at least partially conceived to attract travellers from the Court of Lorraine to reside closer to the city by highlighting the many beautiful villas that had become available. (See R. Harprath, ed., Giuseppe Zocchi: Veduten der Villen und Anderer Orte der Toscana, Munich, 1988)

Presenting the glories of Florence to a broader audience on the international stage was most definitely part of the impetus behind the “Choice” views presented in the Scelta di XXIV Vedute, which Gerini dedicated to Maria Theresa of Austria. This was, after all, the age of vedute. Italian for ‘views’, vedute are essentially topographical renderings of urban or rural areas that contain enough detail to allow for identification. The genre was popular from the late seventeenth century to the Napoleonic Wars, corresponding with the age of the Grand Tour, when wealthy men (and some women) travelled to major cultural sites throughout Europe – and above all those in Italy – to complete their ‘education’. In this context vedute functioned as lavish souvenirs, like monumental postcards, that paid tribute both to the location’s history and the traveller’s experience. And just as Canaletto was the vedutist par excellence for Venice, so Zocchi’s name became synonymous with views of Florence.

Giuseppe Zocchi (1711/6-1767), Pl. VI. Veduta di una parte di Lung' Arno, e del Ponte a S. Trinità presa dal Palazzo del Sig. March. Ruberto Capponi (View along the Arno from the south bank towards the east with the Ponte S. Trinita in the foreground and the Ponte Vecchio behind), from Scelta di XXIV Vedute delle principali contrade, piazze, chiese, e palazzi della Città di Firenze. Giuseppe Allegrini, 1744.

One of the things that makes Zocchi’s work so special is its human dimension. By nature, vedute involve a combination of architectural record and genre scenes, the goal being to present daily life as it unfolds within these great places. But with Zocchi there is a heightened level of human interest, skilfully conveyed by the artist with remarkable grace and wit. Initially trained as a figure painter, his scenes rejoice in a cast of individuated characters and anecdotal detail rendered with penetrative insight, humour, and sympathy.

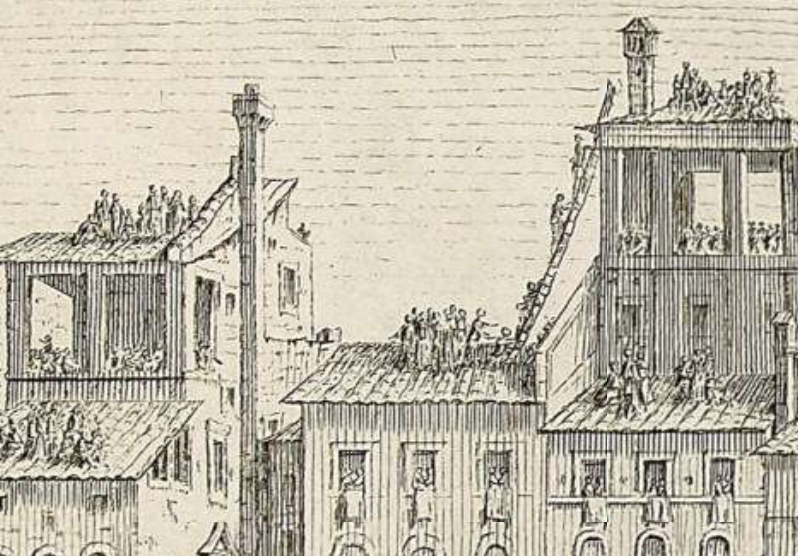

Certainly, the Calcio plate presented here provides a unique entry into the irreverent commotion of Florentine festival life ca. 1739 (Zocchi’s date of 1738 accords with the earlier Florentine convention), with figures in fancy dress and masks circulating among dogs, horse-drawn chariots and people from all walks of life trying to go about their business whilst a horde of viewers gather precisely everywhere, even rooftops, for a chance to witness the fantastic spectacle of calcio fiorentino.

The famous Basilica Santa Croce – the largest Franciscan church in the world (presented, of course, without its nineteenth-century façade) – regally bears down upon them, a monument to the city’s illustrious past. Counting a number of chapels decorated with frescoes by Giotto and his pupils, the basilica is known as the Tempio dell'Itale Glorie (i.e. the Temple of the Italian Glories) and serves as the final resting place for such towering figures as Leon Battista Alberti, Niccolò Machiavelli, Michelangelo Buonarroti, and Galileo Galilei, among myriad others. In the nineteenth century it also became the site of an elaborate, if empty, tomb for Dante Alighieri, whose marble likeness by Enrico Pazzi was also erected in the middle of the piazza in 1865; it later had to be moved from the centre of the square to in front of the basilica to accommodate the piazza’s other claim to fame, its function as the “Teatro del Calcio”.

So, what is il calcio fiorentino? Roughly a mix of football, rugby, and wrestling, bearing a resemblance to American football today. The name comes from the Italian word for ‘kick’ but both feet and hands are allowed. The game is played on a measured dirt pitch with a medium-sized ball and two teams of 27 young men, a main referee, six linesmen, and a field master. The object is to score a caccia by getting the ball passed the other team’s goal line, and most forms of violence were permitted in this endeavour.

Jan Van der Straet (known as Giovanni Stradano; 1523-1605), Calcio in Santa Maria Novella in the Sala di Gualdrada, 1561-1562, fresco, Florence, Palazzo Vecchio.

From this description one might expect to find a rowdy, brawling mass of limbs and dirt at the centre of Zocchi’s print, but the curious gaze is met with just the opposite – spanning the width of the pitch are two teams of well-dressed, well-heeled gentlemen daintily moving in procession with their flag bearers, drummers, trumpeters, and pages, a striking reversal of the wild revelry occupying the foreground.

Sometimes considered a derivation of the Roman game Herpastum, calcio was played in Florence at least as early as the fifteenth century. At that point, members of wealthy banking and mercantile families could readily play alongside those belonging to the labour guilds: the quest for honour was the driving force behind matches, and on this particular “battlefield” it could be won with courage, shrewdness, and physical prowess.

Notably, the teams also represented the city’s historic districts or Quartieri. By the early sixteenth century, when the game was regularly played during carnival on Shrove Tuesday, this meant that it provided a potent metaphor for the social fabric of the Republic:

The Florentine army at this time, although incorporating many mercenaries, was also made up of a core of ‘National Militia’ formed into four battalions – one from each of the four Quartiere – created through the ‘Republican Draft’. This conscription, brought back in 1506 by Machiavelli while he was adviser to the Gonfaloniere of Justice Piero Soderini (1440-1522), came from Machiavelli’s conviction that there is no point discussing ‘the proper form of government unless and until a state could adequately defend itself.’ Thus, in the form of the Quartieri – teams made up of mercenaries and Florentines – the game represented the divided administrative order of the city, but as an event it represented the city’s unity as a singular body. (C. Frost, “The Calcio Storico in Florence”, p. 99)

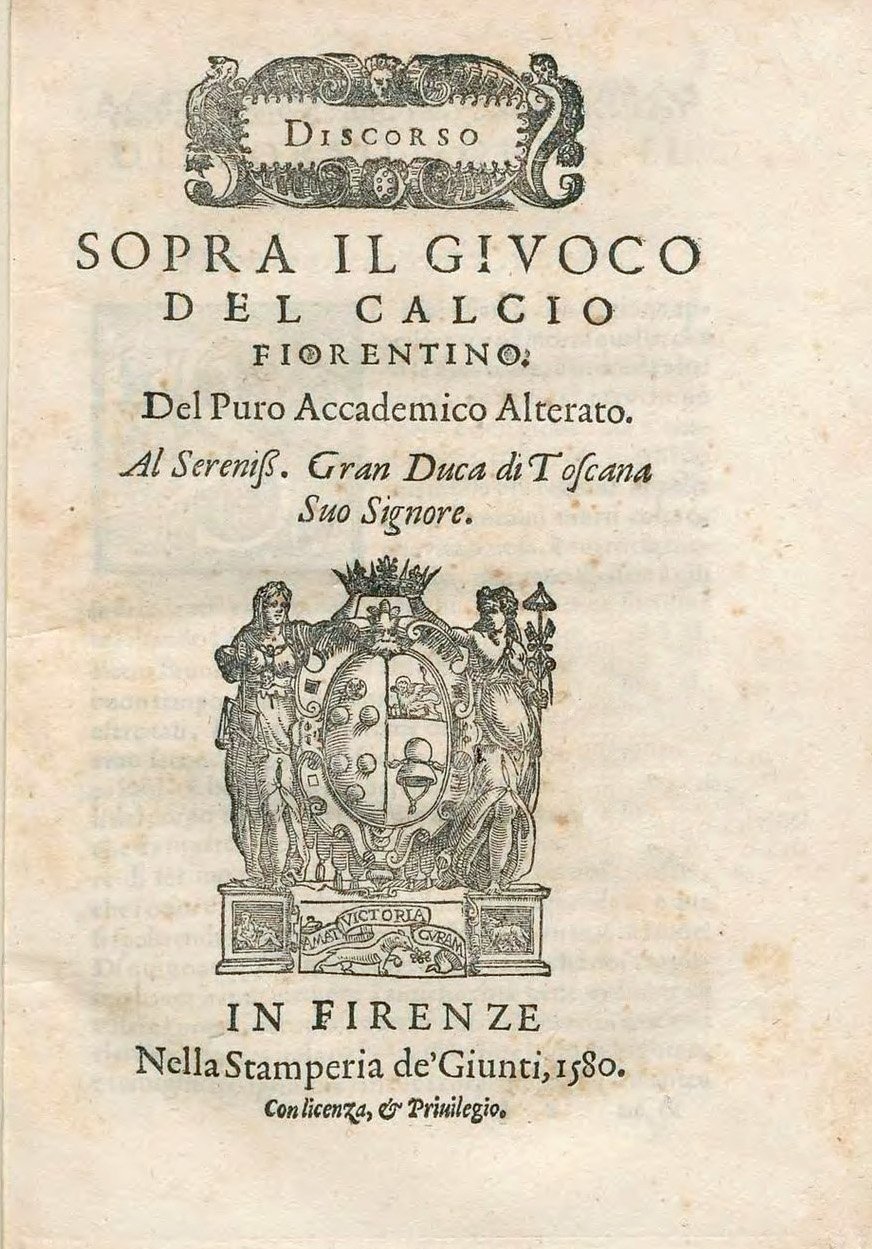

Indeed, as Giovanni de’ Bardi would later remark in the first technical treatise on the sport, calcio was “proprio giuoco nostro Fiorentino” – i.e. justly our own Florentine game – and its connection to the city was deep and resilient. (G. de’ Bardi, Discorso sopra il giuoco del calcio fiorentino del Puro Accademico Alterato, Florence, 1580, p. 4)

View of a Calcio match in Piazza Santa Croce by an anonymous artist, from Giovanni da’ Bardi, Discorso sopra il giuoco del calcio fiorentino, Florence, Giunti, 1580.

The Florentine spirit fostered through calcio was particularly well demonstrated in the most famous match, which took place in the Piazza Santa Croce on 17 February 1530, the square having by then already become the city’s primary calcio arena. Amidst a siege by troops of the Holy Roman Empire and the Papal State, Florentine giovani asserted their independence by holding the annual Calcio, broadcasting their defiance with much visible spectatorship and particularly loud musical accompaniment, continuing the game even despite a canon being fired at the game’s musicians. (Benedetto Varchi, Storia fiorentina, Book XI) As an emblem of courage, the episode became part of Florentine history, and since the 1930s it has been celebrated with an annual calcio match held in the very same piazza.

Soon after the siege, however, the game became intricately tied to the ruling elite. With the establishment of the Medici Duchy in 1532, the game was co-opted by the family’s extremely effective propaganda machine. Spontaneous matches of calcio were still held, but now special “calcio in livrea” became a choice festivity among the numerous forms of celebration arranged for special occasions like aristocratic births, weddings, or visits, always invested with great pomp and pageantry.

The players, too, were now limited to the nobility. In his Discorso, dedicated to Francesco I de’ Medici and first published in Florence by the Giunti in 1580, Giovanni de’ Bardi (himself an influential member of the Florentine elite) stated plainly his justification for reserving participation for the ruling class:

“…si come l’Olimpiade non ammetteva ogni sorte d'huomini: ma i padri delle lor patrie, e Regni, cosi nel Calcio non è da comportare ogni gentame, non Artefici, non servi, non ignobili, non infami, ma soldati honorati, gentilhuomini, Signori, e Principi.”

“…just as the Olympiad did not admit every kind of man, but the fathers of their homelands and kingdoms, so in Calcio it is not every kind of man, not craftsmen, not servants, not the ignoble, not the infamous, but honored soldiers, gentlemen, lords and princes, that should be included.” (Bardi, Discorso, p. 10)

Bardi’s text became the standard reference for calcio, with new editions appearing in 1615, 1673, and 1688, and the text being printed again in 1766. The first three editions each contained a single plate by anonymous artists while the 1688 edition, retitled Memorie del calcio Fiorentino Tratte da diverse Scrittute and published on the occasion of the marriage of Ferdinand de Medici and Violante Beatrice of Bavaria, included a plate by Alessandro Cecchini, along with an additional folded engraving detailing the positions of players on the field. Always the association with the nobility remained clear, and yet the public appeal never seemed to wane.

Title page for Pietro di Lorenzo Bini (ed.), Memorie del calcio fiorentino tratte da diverse scritture e dedicate all'altezze serenissime di Ferdinando Principe di Toscana e Violante Beatrice di Baviera. Firenze, Stamperia di S.A.S. alla Condotta [1688].

Alessandro Cecchini, “Veduta della piazza di S.ta Croce della città di Firenze nel atto di principare il gioco del calcio”, from Pietro di Lorenzo Bini (ed.), Memorie del calcio fiorentino tratte da diverse scritture e dedicate all'altezze serenissime di Ferdinando Principe di Toscana e Violante Beatrice di Baviera. Firenze, Stamperia di S.A.S. alla Condotta [1688].

Indeed, with the exception of a disruption in games as a consequence of the terrible plague epidemic of 1631-33 followed by a certain lessening of interest among the aristocracy, who were increasingly concerned with more elegant and distanced spectacles held in sumptuous interiors (as opposed to combattive brawls in dusty public squares), organized “calcio a livrea” remained an important part of festival culture right up to the end of Medici rule in 1737, hence Zocchi’s stylish nobles performing for the courtly festival. (L. Artusi, Calcio fiorentino, p. 49)

Before the calcio revival of 1930, the match immortalized in Zocchi’s print was the last historical “livery” game to be played in Florence, organized in February 1739 to celebrate that first and only visit of the new sovereigns from the Lorraine dynasty, Francis Stephen, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and Maria Theresa of Austria. From Zocchi’s treatment of the event, it was evidently a great spectacle in keeping with the calcio tradition, even if the event itself marked the decline of the game’s popularity.

Indeed, Zocchi’s vision presents calcio fiorentino as a timeless, seamless part of Florentine culture, one that, despite its association with the ruling class, retained an important place in public life, particularly given the transformative nature of carnival, where stations and classes could be inverted and thought of anew. This calcio would, at least for the moment, provide a sense of consistency within its own dynamic nature, a firmly Florentine celebration that remained of and for the city despite the changing tides of its governance.

How to cite this information

Julia Stimac, “Giuseppe Zocchi and Il Calcio Fiorentino,” PRPH Books, 4 May 2022, www.prphbooks.com/blog/calcio. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.