Updating Ptolemy

A date is especially meaningful in the Renaissance rediscovery of Ptolemy’s Geographia: 13 September 1475, i.e., the date of the first appearance, in print, of its translation into Latin. The version was made in 1406/09 by the humanist Jacopo Angeli (or Angelo, from Scarperia, near Florence), a pupil of Manuel Chrysoloras (ca. 1350-1415), the exiled Byzantine scholar who had brought over several manuscripts of Greek works—including the Geographia composed by Ptolemy in the second century AD—from Constantinople in 1387. Chrysoloras had begun the translation himself, possibly before 1400, on the basis of a hitherto unidentified Greek manuscript. Angeli mainly based his translation on a composite text deriving from two different manuscripts and changed the title from Geographia to Cosmographia. The Latin edition of this landmark geographical text enjoyed wide and enduring popularity. The editio princeps, in Greek, appeared in Basel only in 1533, and the circulation of the Latin text throughout Europe in the fifteenth century greatly influenced (both directly and indirectly) the shaping of the modern world.

Ptolemy’s work, divided into eight books, describes the known inhabited world (or oikoumene), divided into three continents: Europe, Libye (or Africa), and Asia. Book I provides details for drawing a world map with two different projections (one with linear and the other with curved meridians), while Books II-VII list the longitude and latitude of some 8,000 locations, and Book VII concludes with instructions for a perspectival representation of a globe. In the eighth and final Book VIII, Ptolemy breaks down the world map into twenty-six smaller areas and provides useful descriptions for cartographers.

The text published in 1475 was edited by Angelus Vadius and Barnabas Picardus, and issued from the printing house established in Vicenza by the German printer Hermann Liechtenstein, a native of Cologne also known by his surname ‘Leuilapis’. It was one of the first books ever printed in Vicenza, where printing was first introduced in the spring of 1474 by Leonardus Achates, who originated from Basel. The edition is very rare, and it is even rarer to find a copy of this monumental achievement of geographical knowledge still—as with the outstanding, wide-margined copy offered here—in pristine condition and in its strictly contemporary binding of wooden boards, partly covered in brown leather (for the complete description click here).

No maps were issued in this first edition of 1475, and they were probably not present in the manuscript which served as copy-text; the only illustrations included are the three diagrams in chapter XXIV of Book I, showing the ‘modus designandi in tabula plana’, and that depicting the Polus antarcticus.

From 1475 onwards, one of the primary challenges of cosmography has been the updating of Ptolemaic oikoumene (i.e., known land), above all in terms of its visualization. The first illustrated edition of Ptolemy appeared in Bologna in 1477, supplemented with copperplates the drawing of which is usually attributed to the famous painter and illuminator Taddeo Crivelli. Since then, the numerous editions of the Geographia that followed up until the second half of the sixteenth century clearly show this process, gradually adding an increasing number of new tables to the canonical sequence of twenty-six maps illustrating the three continents known to Ptolemy: modern maps which are related not only to the newly discovered Americas, but also to Asia, Africa, and Europe as well, an assemblage in which the tabulae modernae are inserted as an appendix, or more significantly intercalated with the Ptolemaic tables.

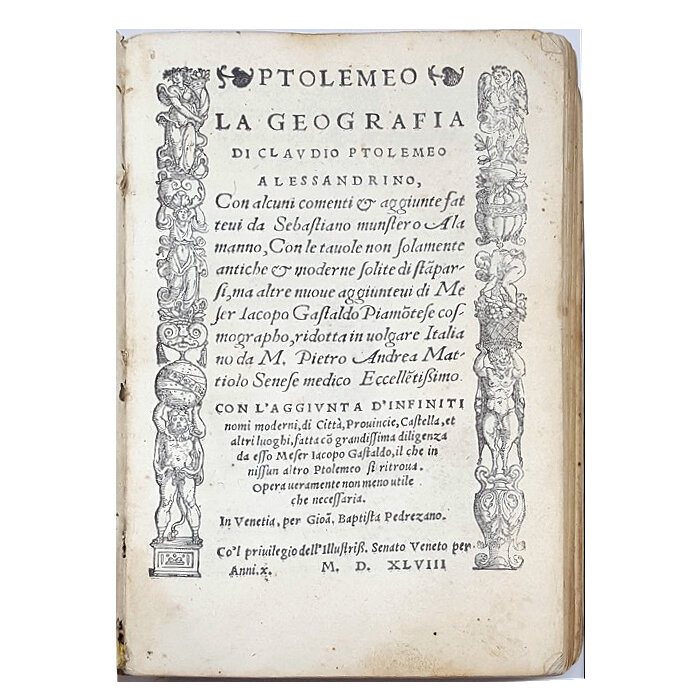

We present here a work that played a very relevant role both in mapping the early modern world and in showing the Renaissance reading of Ptolemy: the first edition of the first Italian vernacular translation of the Geographia, which appeared in Venice in 1548, offered here in a beautiful copy with its original limp vellum binding and complete with all the engraved maps (for the complete description click here).

As of the 1530s, Venice had become an important centre for cartography and the map trade, owing to its broad commercial relationships and the presence of wealthy merchants who were deeply interested in learning about the maritime world and the possibilities of new shipping routes. This demand had favored the birth, in Venice, of workshops specialized in the production of nautical charts, coastal views, topographies, and maps of European countries and the New World. Numerous cartographers therefore came to choose Venice as a privileged place for remunerative activity: among them, the name of Giacomo Gastaldi—responsible for the handsome maps illustrating the Ptolemy of 1548—unquestionably stands out.

Born in Villafranca (Piedmont) around 1500, the engineer, cosmographer, and mapmaker Gastaldi moved to Venice around the end of the 1530s. His name first appears in official documents in 1539, when he was granted a privilege from the Venetian Senate to publish a calender or lunario, now lost. He soon became the most important and sought-after Venetian mapmaker of the sixteenth century, and the Venetian Consiglio dei Dieci (i.e., the Council of Ten) invited him to paint wall maps in the Ducal Palace, also sadly now lost. Gastaldi was active in Venice until 1560, during which time he produced around a hundred maps, making use of all geographic and cartographic information available at the time and benefiting from his close friendship with the geographer, diplomat, and secretary of the Venetian Senate, Giovanni Battista Ramusio (1485-1557), well-known author of the collection of travel accounts Delle Navigationi et Viaggi, which first appeared in 1550 and which includes maps by Gastaldi.

Title page from Claudius Ptolemaeus (ca. 100-168) - Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), Ptolemeo. La geografia di Claudio Ptolemeo alessandrino, con alcuni comenti et aggiunte fattevi da Sebastiano Munstero Alamanno, con le tavole non solamente antiche et moderne solite di stamparsi, ma altre nuove aggiuntevi di messer Iacopo Gastaldo piamontese cosmographo, ridotta in volgare italiano da m. Pietro Andrea Mattiolo [...], Venice, Niccolò Bascarini for Giovanni Battista Pederzano, October 1547.

The Geografia of 1548 represents a groundbreaking publishing initiative in many regards. It aimed at disseminating geographical knowledge to a broader reading public, thus departing from the earlier tradition of Ptolemy editions written in Latin, issued in large format, and addressed to a more scholarly audience. The work was, in effect, not only rendered more accessible from a linguistic point of view, but from a practical one as well, since for the first time in the history of printing it was offered as a pocket-size publication: it is the first ‘atlas’ ever printed in the octavo format. As Gastaldi himself wrote in his address to readers, the publication was intended not only for princes and rulers, condottieri, captains and admirals of fleets, but also for sailors, soldiers, merchants, gentlemen and dames (gentilissime Madonne), wayfarers, and pilgrims: a portable instrument for travelling, studying, reading, or simply viewing the world through the pages of a book.

Claudius Ptolemaeus (ca. 100-168) - Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), Ptolemeo. La geografia di Claudio Ptolemeo alessandrino, con alcuni comenti et aggiunte fattevi da Sebastiano Munstero Alamanno, con le tavole non solamente antiche et moderne solite di stamparsi, ma altre nuove aggiuntevi di messer Iacopo Gastaldo piamontese cosmographo, ridotta in volgare italiano da m. Pietro Andrea Mattiolo [...], Venice, Niccolò Bascarini for Giovanni Battista Pederzano, October 1547.

The translation was made by the renowned physician from Siena Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501-1577), well known for his edition of Dioscorides’ De materia medica, which first appeared in Italian vernacular in Venice in 1544 as an unillustrated edition (notably printed by Niccolò Bascarini, the same printer responsible for Gastaldi’s Geografia), followed in 1554 and 1565 by enlarged and splendidly illustrated Latin editions (see the complete description of the 1565 edition here). For his translation, Mattioli did not rely directly on the original Greek text, but rather on Wilibald Pirkheimer’s Latin translation, as it was corrected and emended by renowned German cartographer and Hebraist Sebastian Münster (1488-1552)—the well-known author of the monumental Cosmographia (1544), the most famous cosmography of the Renaissance—for the Ptolemy published in Basel in 1540.

Gastaldi was entrusted with the illustrative apparatus supplementing Mattioli’s Italian translation. The volume would only be published in 1548, but the cartographer had already gotten to work on the illustrations by the early 1540s, as attested by the map of Germany (Germania nova tabula, no. 9), the inscription for which bears the year ‘1542’ as the date of execution. Gastaldi produced a total of sixty double-page maps, all newly drawn and engraved in copper. The maps are mainly signed with the letter G, generally visible at the corner of the frame, and obviously designating Gastaldi.

The use of copperplate engravings in the service of cartography had fallen into disuse in the first half of the sixteenth century until the appearance of this Venetian edition: this pocket-size publication was the first to re-introduce the process and made it something of a necessity moving forward, as the technique was uniquely able to ensure a high level of quality and accuracy in the rendering of cartographic details despite the small format adopted for the volume. The traditional woodcut technique was reserved for the border framing the title-page, the in-text illustrations and diagrams, and the portrait of Ptolemy as the ‘Prince of the Astronomers’ on fol. ☩2r, where he is depicted holding an astrolabe in his hands, an indispensable instrument in the compilation of astronomical tables.

Gastaldi’s tabulae are set in the traditional Ptolemaic grid of meridians and parallels. Explanatory texts are printed on the verso, mainly taken from the aforementioned Latin Ptolemy published by Münster in 1540. Of the sixty maps realised by Gastaldi for the Geografia of 1548, twenty-six belong to the Ptolemaic canon, mapping the old world. These are complemented by thirty-four modern maps or the tabulae modernae, in order to improve illustration according to the new voyages of discoveries, and to reflect the developing geographical knowledge of Europe itself. Significantly, the tabulae modernae relating to Europe, Africa, and Asia are not inserted as an appendix, but rather intercalated with Ptolemy’s canonical tables, offering a unique, updated sequence, and revealing how the Ptolemaic order was still considered the most authoritative, and above all substantially flexible representation of the world. The sequence opens with the first map of Ancient Europe (“Tabula Europae I”) depicting the British Islands, followed by the modern map titled “Anglia et Hibernia Nova”, while the “Tabula Europae VI” is updated with the Italia nova tabula, which is in turn followed by the first modern regional maps of Italy ever produced, including those of Piedmont (“Piemonte Nova Tavola”), the Marca Trevisana (“Marcha Trevisana Nova Tavola”), and the Marca Anconetana (“Marcha de Ancona Nova”). The tabula europae vii is followed by the modern maps of Sicily and Sardinia (“Sicilia Sardinia Nova Tabula”).

Claudius Ptolemaeus (ca. 100-168) - Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), Ptolemeo. La geografia di Claudio Ptolemeo alessandrino, con alcuni comenti et aggiunte fattevi da Sebastiano Munstero Alamanno, con le tavole non solamente antiche et moderne solite di stamparsi, ma altre nuove aggiuntevi di messer Iacopo Gastaldo piamontese cosmographo, ridotta in volgare italiano da m. Pietro Andrea Mattiolo [...], Venice, Niccolò Bascarini for Giovanni Battista Pederzano, October 1547.

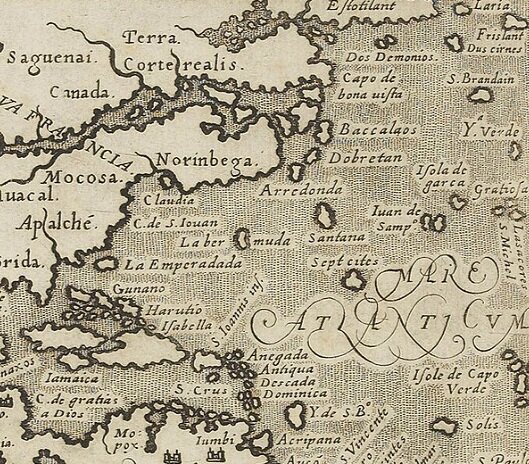

The final maps of the Geografia are obviously those depicting the Americas, i.e., the part of world still unknown to Ptolemy, and the edition is indeed rightly defined by Nordenskiöld as “the very first atlas of the New World”. In fact, Gastaldi’s five detailed maps devoted to the New World are of the greatest importance, representing the earliest American regional maps ever printed: the “Tierra Nova” (South America), “Nueva Hispania Tabula Nova”, “Tierra Nueva” (Eastern North America), and separate maps of Cuba and Hispaniola (now the Dominican Republic), bearing the titles “Isola Cuba Nova” and “Isola Spagnola Nova”, respectively.

“Isola Spagnola Nova” map by Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), from Claudius Ptolemaeus (ca. 100-168) - Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), Ptolemeo. La geografia di Claudio Ptolemeo alessandrino, con alcuni comenti et aggiunte fattevi da Sebastiano Munstero Alamanno, con le tavole non solamente antiche et moderne solite di stamparsi, ma altre nuove aggiuntevi di messer Iacopo Gastaldo piamontese cosmographo, ridotta in volgare italiano da m. Pietro Andrea Mattiolo [...], Venice, Niccolò Bascarini for Giovanni Battista Pederzano, October 1547.

The “Tierra Nueva” map, i.e., the map of Eastern North America and representing the Atlantic coast from Labrador to Florida, deserves special attention. Remarkably, this map contains the first mention in printed cartography of the ‘Tierra de Nuremberg’ (Norumberga, or Noruberga), a designation used by cartographers from 1548 until 1614, when Captain John Smith renamed the region New England. The ‘Tierra de Nuremberg’ (the etymology of which is still debated) was first noticed by the Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano (1485-1528) during his 1524 voyage to the New World on behalf of Francis I, King of France. What’s more, Gastaldi’s coastline includes the mention of the harbor ‘Angoulesme’, so named by Verrazzano in honour of the French King, known before his ascent to the throne as the Count of Angoulême: it is the first European name for New York Bay. Gastaldi’s map is also in all likelihood the first to record the travels of the French navigator Jacques Cartier (1491-1557) to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in Eastern Canada between 1534 and 1542.

“Tierra Nueva” map by Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), from Claudius Ptolemaeus (ca. 100-168) - Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), Ptolemeo. La geografia di Claudio Ptolemeo alessandrino, con alcuni comenti et aggiunte fattevi da Sebastiano Munstero Alamanno, con le tavole non solamente antiche et moderne solite di stamparsi, ma altre nuove aggiuntevi di messer Iacopo Gastaldo piamontese cosmographo, ridotta in volgare italiano da m. Pietro Andrea Mattiolo [...], Venice, Niccolò Bascarini for Giovanni Battista Pederzano, October 1547.

Finally, the last two maps included show the whole world now known: the “Universale Novo”, which is a reduced version of Gastaldi’s first world map published separately in 1546, and the navigational chart “Carta Marina Nova Tabula”, which clearly represents Asia and America as a unique continent, connected to Northern Europe through Greenland. Both maps contain one of the earliest appearances in print of the California peninsula.

“Universale Novo” map by Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), from Claudius Ptolemaeus (ca. 100-168) - Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), Ptolemeo. La geografia di Claudio Ptolemeo alessandrino, con alcuni comenti et aggiunte fattevi da Sebastiano Munstero Alamanno, con le tavole non solamente antiche et moderne solite di stamparsi, ma altre nuove aggiuntevi di messer Iacopo Gastaldo piamontese cosmographo, ridotta in volgare italiano da m. Pietro Andrea Mattiolo [...], Venice, Niccolò Bascarini for Giovanni Battista Pederzano, October 1547.

“Arta Marina Nova Tabula” map by Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), from Claudius Ptolemaeus (ca. 100-168) - Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-1566), Ptolemeo. La geografia di Claudio Ptolemeo alessandrino, con alcuni comenti et aggiunte fattevi da Sebastiano Munstero Alamanno, con le tavole non solamente antiche et moderne solite di stamparsi, ma altre nuove aggiuntevi di messer Iacopo Gastaldo piamontese cosmographo, ridotta in volgare italiano da m. Pietro Andrea Mattiolo [...], Venice, Niccolò Bascarini for Giovanni Battista Pederzano, October 1547.

Significantly, the 1548 Geografia does not contain any ‘old’ world map, intending to present itself as the visualization of the Renaissance oikoumene, including the Americas.

The portable Ptolemy was never reprinted, but the maps included had a wide circulation, and many of them were later copied or revised by such outstanding cartographers as the great Gerard Mercator, Jodocus Hondius, Abraham Ortelius, and Willem and Joan Bleau. Particularly noteworthy in this regard is the world map “Universale Novo”, which is considered one of the most important maps of the sixteenth century and was adopted by Ortelius in his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum of 1570.

In the history of Italian cartography, a group of Gastaldi’s maps were re-used—mainly on a larger scale and with minor changes—in subsequent editions of the Geographia, especially in the new Italian translation made by Girolamo Ruscelli, first printed by the Venetian printer Vincenzo Valgrisi in 1561, and thereafter frequently reprinted until 1598. Some maps were also included in the Latin Ptolemy of 1562, edited by the mathematician Giuseppe Moleti and issued in folio size, likewise from the Valgrisi press (see the full description of our available copy here).

Title page from Claudius Ptolemaeus (ca. 100-168) - Giuseppe Moleto (1531-1588), Geographia Cl. Ptolemaei Alexandrini Olim a Bilibaldo Pirckheimherio traslata, at nunc multis codicibus graecis collata, pluribusque in locis ad pristinam ueritatem redacta a Iosepho Moletio mathematico, Venice, Valgrisi Vincenzo, 1562.

Girolamo Ruscelli’s “Tierra Nueva” map in Claudius Ptolemaeus (ca. 100-168) - Giuseppe Moleto (1531-1588), Geographia Cl. Ptolemaei Alexandrini Olim a Bilibaldo Pirckheimherio traslata, at nunc multis codicibus graecis collata, pluribusque in locis ad pristinam ueritatem redacta a Iosepho Moletio mathematico, Venice, Valgrisi Vincenzo, 1562.

The influence of Gastaldi’s maps is also recognizable in the Universale fabrica del mondo, overo Cosmografia by geographer Gianni Lorenzo da Anania (1545-1609), which first appeared in Naples in 1573 and contains, along with an engraved map titled “Orbis Descriptio”, four engraved maps of the continents known at the time, depicting Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The name ‘Giacomo Gastaldo’ is entered in the preliminary list of sources referenced, and the map bearing the title “America” includes the land of ‘Norinbega’, closely following Gastaldi’s model.

Anania’s work was well appreciated, and two editions followed in Venice in the sixteenth century, in 1576 and 1582, respectively. We present here the Venetian edition of 1582, in an exceptional copy once preserved in the celebrated library assembled by the Pillone family over several generations in their Villa of Casteldarno in Val Cadore, near Belluno (for a complete description click here). The volume is housed in a magnificent vellum binding decorated with India ink and wash drawings by Cesare Vecellio (1521-1601), a cousin and pupil of Titian. The Pillone Library was large and varied, and well supplied with geographical books and travel narratives. This copy of Anania’s Universale fabrica del mondo or Cosmografia is one of only twenty-one volumes bound in vellum whose covers were finely decorated by Vecellio with drawings appropriate to the content of the book: on the upper cover, the artist depicts a map of Europe, Asia, and Africa, while the lower cover bears a map depicting the Mondo Novo.

Decorated upper cover by Cesare Vecellio (1521-1601), with map of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Gianni Lorenzo da Anania (1545-1609), L’uniuersale fabrica del mondo, overo Cosmografia... Diuisa in quattro Trattati... Di nuouo ornata con le figure delle quattro parti del Mondo in Rame, Venice, Andrea Muschio for Giacomo Aniello De Maria, 1582.

Decorated lower cover by Cesare Vecellio (1521-1601), with map of the New World (Mondo Novo). Gianni Lorenzo da Anania (1545-1609), L’uniuersale fabrica del mondo, overo Cosmografia... Diuisa in quattro Trattati... Di nuouo ornata con le figure delle quattro parti del Mondo in Rame, Venice, Andrea Muschio for Giacomo Aniello De Maria, 1582.

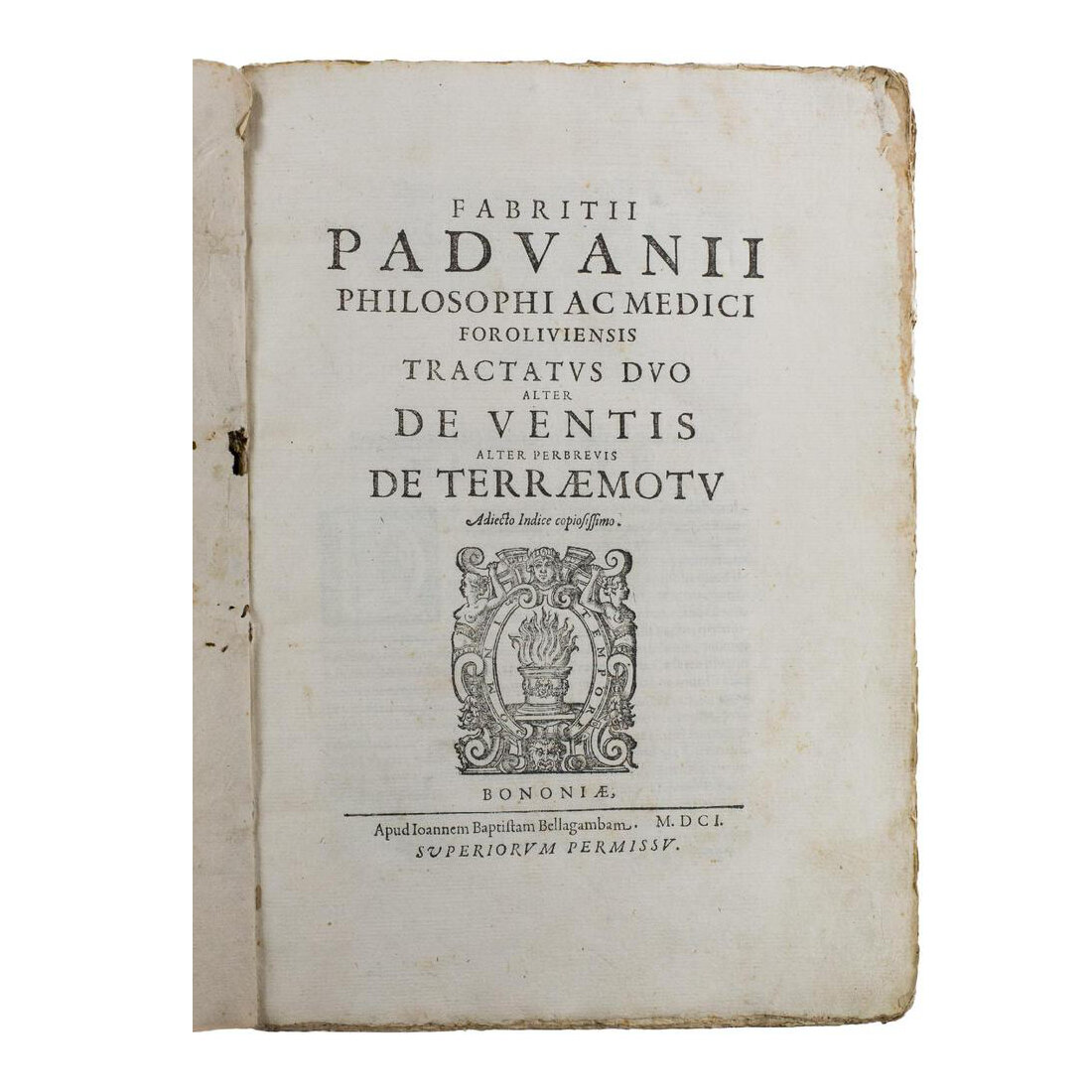

Finally, a re-use of Gastaldi’s cartography is also found in one of the most finely illustrated Italian books produced in the early seventeenth century, the Tractatus duo, alter De Ventis, alter perbrevis De Terraemotu by the ‘philosophus ac medicus’ from Forlì, Fabrizio Padovani, which appeared in Bologna in 1601 (for a complete description click here). As stated on the title-page, the work addresses the effects of wind, with the last leaves concerning earthquakes, as it was traditionally believed these could be caused by subterranean winds.

The volume is supplemented with an illustrative apparatus of the highest quality, including a total of thirty-nine engraved maps and plates of wind roses, compasses, and other technologies.

Padovani’s Tractatus duo also contains two full-page charts of the world, both showing the Americas in Gastaldi’s style. One of these closely recalls the famous nautical chart executed by the Piedmontese mapmaker for the ‘small’ Ptolemy of 1548, offering clear evidence of the lasting influence of this Venetian edition and its essential role in updating the Ptolemian visualization of the world.

How to cite this information

Margherita Palumbo, "Updating Ptolemy," 8 January 2020, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/updatingptolemy. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.