Pablo Picasso and Max Jacob

This week we are highlighting a selection of special copies from the collection of M. A * * * celebrating the friendship and collaboration between Pablo Picasso and the French poet and artist Max Jacob (1876-1944). The two met in 1901, after a 19-year-old Picasso settled in Paris, and formed a deep friendship. At first, the two communicated via Picasso’s Paris dealer, Pedro Manac, as well as through sign language, until Jacob helped the Spaniard with his French. Jacob is also said to have introduced the young artist to the French literary avant-garde scene, including such figures as Guillaume Apollinaire. Apollinaire, in turn, is responsible for making the acquaintance between Picasso and Georges Braque, his “co-founder” in the development of Cubism. Picasso’s illustrations for Jacob’s Saint Matorel (1911) are considered critical works in his own development of the style, as discussed below. Picasso likewise had great influence on Jacob, who described his poetry as “Cubist,” as with Le cornet à dés of 1917, for which Picasso contributed the only known harlequin rendered in his Cubist style.

Jacob was Jewish by birth but converted to Roman Catholicism in 1909, a transition reflected in Saint Matorel (1911) and La Défense de Tartufe (1919). He was, nonetheless, arrested by the Gestapo on 24 February 1944. He died in the internment camp at Drancy on 5 March of that year.

Picasso: Les livres d’artiste, The collection of Mr. A *** is currently on view at PrPh until November 23. See the complete catalogue of the collection here.

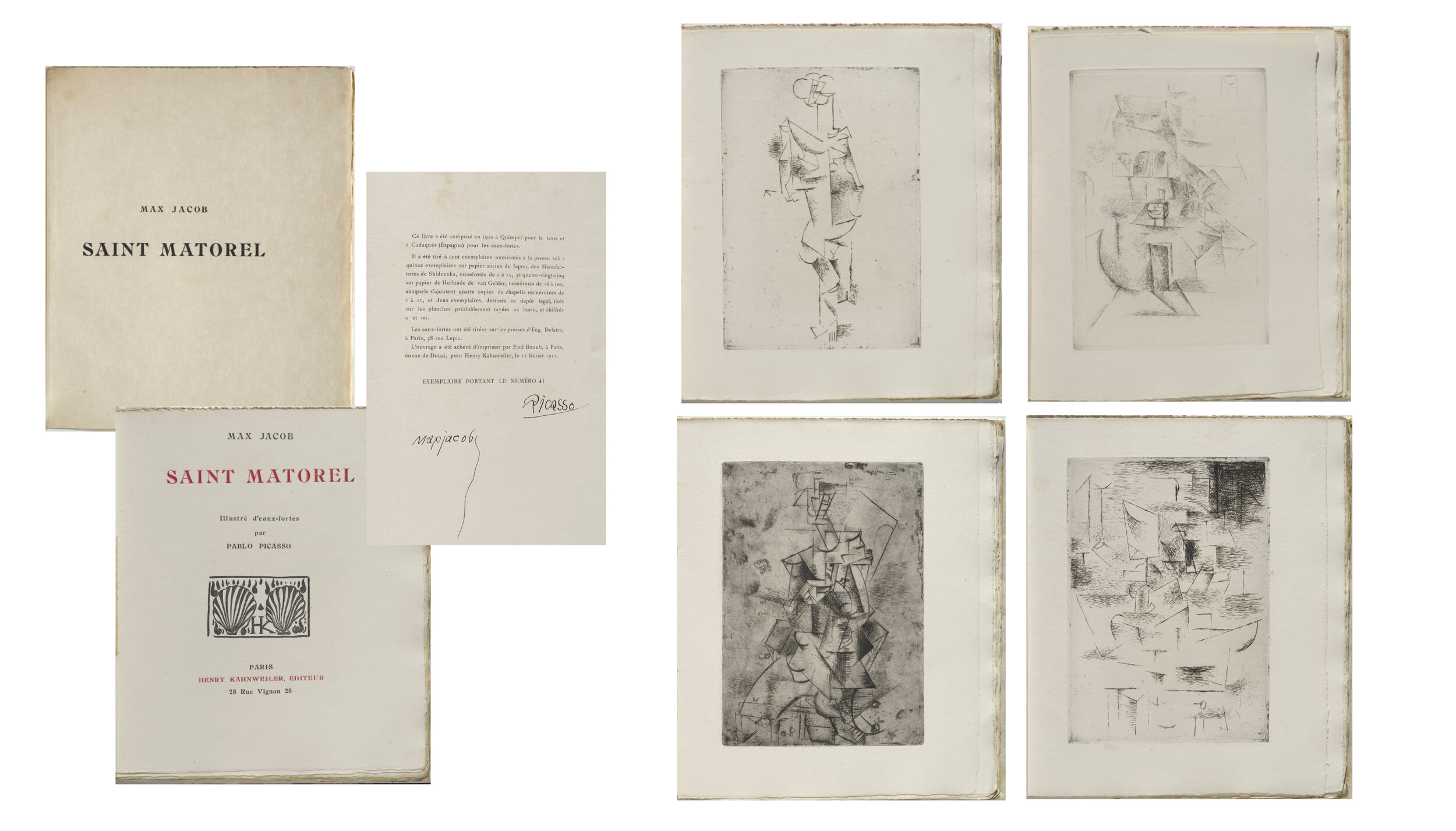

Max Jacob, Saint Matorel, 1911

Edition: 106 copies (15 copies on ancient japan, numbered from 1 to 15; 85 copies on van Gelder holland laid, numbered from 16 to 100; 4 copies on van Gelder holland laid, numbered from I to IV; 2 deposit copies with impressions of the canceled plates, marked 0 and 00. All copies are signed in ink by the author and the artist.)

Printing: (February 11, 1911). Paul Birault, Paris, for the text and typography. Les Presses Eugène Delâtre, Paris, for the etchings.

Saint Matorel was the first book of the so-called ‘Matorel-Jacob’ trilogy. It was followed by Les oeuvres brulesques et mystiques de Frère Matorel in 1912, illustrated by André Derain, and Le siège de Jérusalem in 1914, illustrated by Picasso. The artist produced a number of etchings for the project over the summer of 1910, four of which were ultimately selected for the publication.

Jacob’s bizarre, semi-autobiographical tale follows the religious experience of Victor Matorel until his ultimate retreat to the monastery of Saint Teresa at the end of his life. Picasso was particularly taken with Mademoiselle Léonie, the hero’s great love, and represents her in two of his four illustrations. The other two represent a table still life and the Saint Teresa monastery, respectively. Of course, this is not immediately obvious, as Picasso rendered the illustrations in his Analytic Cubist style. This early phase of Cubism sought to deconstruct the traditional modes of image-making by fragmenting the object and faceting space. One can still trace elements of the figures or scenes in Picasso’s “illustrations”; indeed, as abstract as his works may seem, Picasso always resisted complete abstraction. Thus, Madame Léonie can be “found” in certain details like the arc of a breast, though angular lines and dense cross hatching work to fracture the planes.

The forward-looking Kahnweiler was an early supporter of Picasso’s Cubism. As he later wrote, when Picasso produced these etchings in the summer of 1910, he began “to blow up the coherent form” (B. Baer, Picasso the Printmaker, Dallas 1983, p. 36). Indeed, today, Picasso’s Saint Matorel etchings are considered defining works of Cubist printmaking.

This is number 41 from the edition of 85 printed on Vergé Holland van Gelder, signed in ink by the author and the artist.

Sm. 4to (265 x 223 mm). [52] leaves including half title, title page printed in black and red with a woodcut vignette by André Derain with the monogram ‘HK’, and justification with the signatures of the artist and the author at the bottom. Editor’s japan wrappers with lettering on the front cover. Uncut.

Max Jacob, Le Siège de Jérusalem, 1914

Printing: (January 21, 1914). Paul Birault, Paris, for text and typography. Les Presses Eugène Delâtre, Paris, for the prints.

Edition: 106 copies (15 copies on ancient japan, numbered from 1 to 15; 85 copies on van Gelder holland laid, numbered from 16 to 100; 4 chapelle copies on van Gelder holland laid, numbered from I to IV; 2 deposit copies with impressions from the canceled plates, marked 0 and 00. All the copies are signed in ink pencil by the author and the artist.)

Le siège de Jérusalem is the third book of the so-called ‘Matorel-Jacob’ trilogy. It was preceded by Saint Matorel (1911), illustrated by Picasso, and Les oeuvres brulesques et mystiques de Frère Matorel (1912), illustrated by André Derain. Although Derain was the initial impetus for the project, the artist declined to illustrate what he considered to be a strange mixture of literary genres; the art dealer, writer, and publisher Henry Kahnweiler thus turned to Picasso, who readily agreed to the work, particularly given his close relationship with Jacob. For Le siège de Jérusalem, Picasso provided three etchings and drypoints, completed in the winter of 1913/14.

Jacob’s story shifts between dream and nightmare and involves a multitude of characters fighting around Matorel in an apocalyptic war for the conquest of celestial Jerusalem. Although Picasso provided an illustration for each act – two female nudes and a still life with a skull – they bear little relation to the text and are visually difficult to discern as Cubist cacophonies of evaporating shapes and dense shading. In this way, however, the illustrations capture the abstract nature of Jacob’s ideas while visually echoing the ambiguity of the text.

This is number 26 of 85 copies on van Gelder holland laid, numbered 16 to 100, signed in ink by the author and the artist on limitation page.

8vo (218 x 150 mm). [76] leaves. Editor’s japan wrappers with lettering on the front preserved. Bound by Jacques Anthoine Legrain in large-grain black gilt morocco with red and black insets forming a leaf motif, gilt edges, red suede pastedowns and flyleaf. Smooth spine with author’s and artist’s names and title in gilt. Half-morocco chemise with smooth spine bearing the name of the author and the title in gilt, and matching slipcase, signed by Legrain.

This is a special copy, bound by Pierre Legrain, containing a long note by Max Jacob to an anonymous friend in which he declares to have used, for the first time, his astrological knowledge to the construction of characters. It also includes seven original drawings (three folding) depicting characters from the book, executed by Jacob with manuscript captions; another autograph note on the half title, in which Jacob states how it made sense, in 1914, that Picasso should illustrate his works as at the time they were never apart from one another.

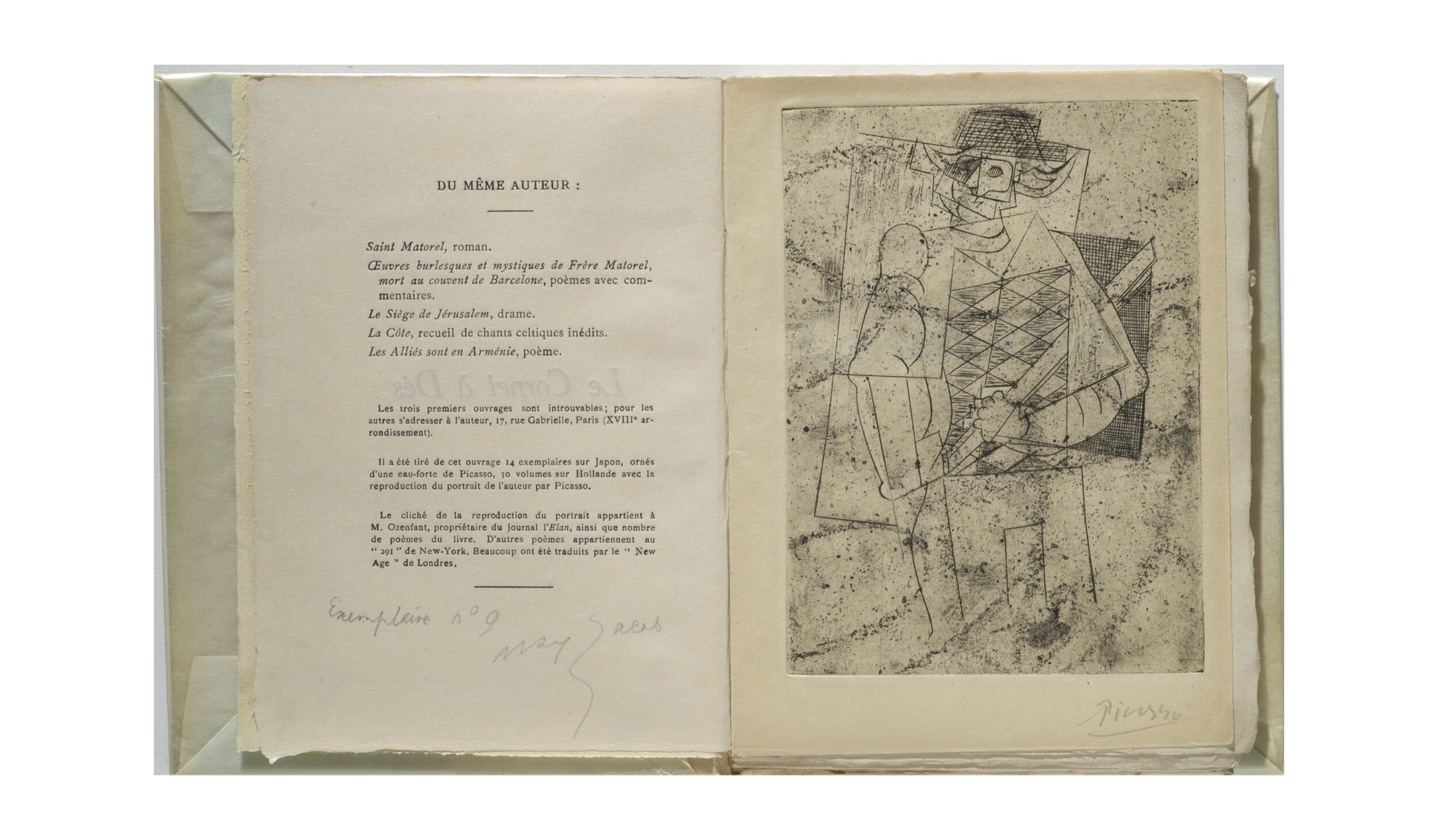

Max Jacob, Le cornet à dés, 1917

Printing: [1917]. Imprimerie Levé, Paris, for the text and typography. [Les Presses Eugène Delâtre, Paris, for the engraving.]

Edition: 44 copies (14 copies on Vieux Japon, with the engraving, signed in black ink by the author, numbered from 1 to 14; 30 copies on holland, with a reproduction of a portrait of the author by Picasso, numbered from 15 to 44).

Max Jacob conceived of the majority of the 300 prose poems included in this groundbreaking work between 1904 and 1910, though it was not until 1917 that the poet, artist, and critic finally managed the nerve and financial backing to realize their publication. Suffuse with puns, the varied texts combine in a sort of organized chaos like the roll of a dice, an image he captures in the title, Le Cornet à Dés, à cause de la diversité de leurs aspects et du côté hasardeux de l’ensemble. The shifting, striking, ambiguous forms developed in the poems work together in the reader, as Jacob emphasizes the constructedness of the poem and the unique aesthetic experience one has upon engaging with it.

Picasso’s engraving for the 14 deluxe editions is a fine example of Synthetic Cubism. Whereas the earlier phase of Analytic Cubism sought to deconstruct the image by fragmenting objects and faceting space in order to consider a multitude of viewpoints and perspectives, Synthetic Cubism, sought to reconstruct those fragmented pieces into new kinds of reality, emphasizing interlocking shapes and the development of collage. The shift to Synthetic Cubism was also accompanied by a shift toward lighter subject matter (and, in painting, to brighter colours); for Picasso this meant the reappearance of the harlequin, the artist’s alter ego. But despite the character’s heavy use in Picasso’s paintings of the period, the engraving included here is the only known print of the harlequin in Picasso’s Cubist style. This is particularly surprising since the paper support is ideally suited to Synthetic Cubism’s goal of ultimate flatness, a fact Picasso seems to stress through the multiple rectangles that both frame and make up the harlequin’s body.

This is number 9 of 14 on Vieux Japon, with the engraving, signed in black ink by the author, numbered 1 to 14.

8vo (202x155 mm). 96 leaves. Uncut, original wrappers preserved in a half-morocco chemise signed “A. Devauchelle”, with matching slipcase. Smooth spine with author’s name, title, date, and “Eau-forte de PICASSO” in gilt.

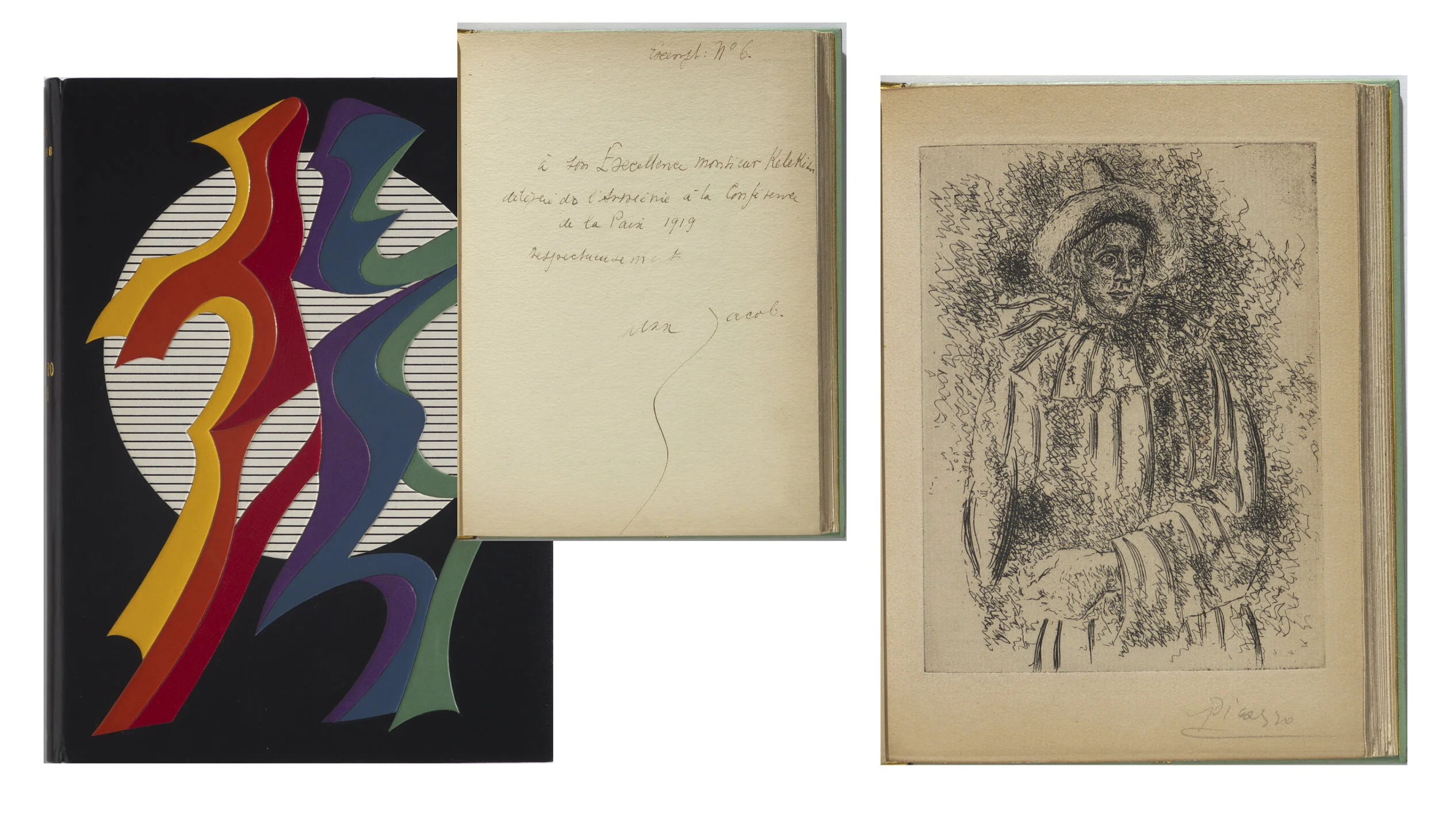

Max Jacob, Le Phanérogame, 1918

Printing: [1918]. Imprimerie Levé, Paris, for the text and typography. [Les Presses Eugène Delâtre, Paris, for the etching].

Edition: [20 copies on Vieux Japon.]

To help pay for the printing of Le Phanérogame, Picasso produced an etching of a Pierrot to be included with the deluxe edition. Jacob dedicated the work “to the poet, André Salmon, in memory of the rue Ravignan”, the site of the “Bateau-Lavoir” where Jacob, Picasso, Salmon, and Apollinaire congregated and collaborated so fruitfully in the early years of their careers. He further explained the text as reflecting “the gaiety of that first youth which is the golden age of art”.

In the spring of 1918 Picasso was working on a series of works inspired by the theatre, particularly the Commedia dell’Arte, but the subject was hardly new: harlequins, jesters, and acrobats feature prominently in his work during the years recalled by Jacob, prompting some to describe it as his Circus Period. During that time, the young group visited the circus frequently, feeling deep sympathy for the performers. It is fitting, then, that Picasso produced an engraving of Pierrot for Jacob’s book. Though Picasso’s model was likely the dancer and choreographer Léonide Massine, the pensive clown also recalls his earlier saltimbanque figures and their close association with his circle. For example, Apollinaire, Jacob, and Salmon are unerstood to represent the three male figures in Picasso’s famous painting The Family of Saltimbanques of 1905, the period recalled in Salmon’s book. That same year Picasso also used Jacob as the model for his sculpture Head of a Jester, which had begun as a portrait one evening after the group returned from the circus. Apollinaire died in November 1918, and while the timing had to have been coincidental, with Picasso’s etching, Salmon’s tribute to the group’s artistic youth takes on an extra elegiac function.

This is number 6, as written by the author. Printed sur Vieux Japon, the etching printed on Arches laid and signed in pencil by the artist. With a signed dedication by the author: “Exempl: N° 6, à son Excellence Monsieur Kelekian délégué de l’Arménie à la Conférence de la paix 1919, respectueusement Max Jacob.”

8vo (190 x 137 mm). [4], 96, [4] leaves including half-title and title page. Black leather binding signed by Paul Bonet and dated 1963, with modern design composed of yellow, orange, red, purple, blue, and green, forming arabesques superimposed upon a white and black striated circle. Yellow suede pastedowns and flyleaf, framed in light green. Smooth spine with author, title, and date in gilt. Gilt edges; original wrappers preserved. Housed in a quarter-leather chemise with matching case.

This copy contains a dedication by Jacob to Dikran Kelekian, who, as the author notes, served as the Armanian delegate at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Kelekian was a prominent collector of modern paintings and Coptic and Islamic art, as well as an important dealer in Middle Eastern art across all periods. His portrait was painted by such noted artists as Mary Cassatt and Milton Avery.

Max Jacob, La Défense de Tartufe, 1919

Printing: (November 22, 1919). Hérissey, Evreux, for the text and typography. [Les Presses Eugène Delâtre, Paris, for the engraving.]

Edition: 830 copies (25 on Rives wove, with the engraving, numbered from 1 to 25; 25 on Rives wove, with drawings by Max Jacob, numbered from 26 to 50; 30 on Rives wove, numbered from 51 to 80; 750 on brown paper, numbered from 81 to 830.

Along with Saint Matorel (1911), La Défense de Tartufe describes Jacob’s religious experience through the diary of a convert who feels surrounded by temptation. It is dedicated to Juan Gris, one of the early “members” of the Bateau-Lavoir group; the group also included, among others, Apollinaire and Salmon, to whom Saint Matorel and Le Phanérogame are dedicated, respectively.

Picasso – who was made godfather to Jacob when the latter was baptized in 1915, the same year Picasso returned to realistic imagery – contributed an engraving of a head of a woman to Jacob’s publication. He had created the engraving three years earlier, in 1916. Deborah Wye suggests this print is a “rare likeness” of Eva Gouel (née Marcelle Humbert), Picasso’s lover and muse between 1912 and 1915, when the young woman died. Because this coincides with the artist’s most abstract phase of Cubism, Gouel is difficult to “find” amongst Picasso’s works, though she can be traced in such celebrated pieces as Ma Jolie (1912). Wye further observes how the artist’s use of the roulette tool “creates evocative shadows and gives his representation a sense of memory more than reality” (D. Wye, A Picasso Portfolio, New York 2010, p. 120). In the intriguing sectioning of her face, there is also a connection to Picasso’s first Cubist sculpture of 1909, a faceted bust of Fernande Olivier, Picasso’s lover and muse from the days of the Bateau-Lavoir.

This is number 2 of 25 on Vélin de Rives, with the engraving signed in pencil by the artist. 16mo (165 x 130 mm). [4], 213, [3] pp., including half title, title page, justification, and table of contents. Original greenish wrappers with lettering on front cover and spine preserved. Slipcase and box.

This copy is accompanied by two autograph letters by Max Jacob to an unidentified “Mademoiselle”, both dated 1919 and relating to a gouache painting he had sent her.

Max Jacob, Chronique des temps héroïques, 1956

Edition: 170 copies, on Montval laid (30 copies with a suite on ancient japan, numbered from 1 to 30; 120 copies, numbered from 31 to 150; 20 copies, numbered from I to XX. All copies are signed in pencil by the artist.)

Printing: (October 24, 1956). Imprimerie Union, Paris, for the text and typography. Atelier Desjobert, Paris, for the lithographs. Atelier Georges Leblanc, Paris, for the drypoints. Georges Aubert, Paris, for the incision of the wood-engravings.

This book was published in 1956, on the 80th anniversary of Max Jacob’s birth, well after his death at a concentration camp at Drancy in 1944. The text actually comes from Jacob himself and consists of a set of recollections written at the request of Domenica Guillaume (née Juliette Léonie Lacaze, later Mme Jean Walter); in 1935, she had asked Jacob to contribute to a book she intended to make in memory of her late husband, the art dealer Paul Guillaume, who had passed away in 1934, though the project was ultimately abandoned. Paul Guillaume had been one of the few art dealers interested in Cubism before the First World War, and he was among the first to sell Cubist art when Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (its primary dealer) was exiled during the war. His interest in African art, which he shared with Apollinaire and Picasso, was also ahead of its time, and he traded in and organized several exhibitions on this subject as well. In his recollections, written between 1935 and 1936, Jacob places the impressive dealer within the context of the first three decades of the 20th century, discussing Picasso and Apollinaire, artistic developments and the avant-garde scene more generally, and even the cabarets of Montmartre, where Domenica Guillaume had worked early on.

For this tribute to Jacob, Picasso contributed three drypoint portraits of his beloved friend, all produced on 7 September 1956. They include one of the poet writing, a nude seen from behind, and a portrait in profile. He also made two colour lithographs for the cover and slipcase, and a lithographic portrait he had drawn of Jacob on 23 September 1953 came to serve as the frontispiece.

This is exemplaire d’exposition II/III not present in Cramer. Signed by the artist at the limitation page.

Sm. 4to (252 x 190 mm). Loose in Montval laid wrappers with a lithograph on the covers and spine. Laid paper-covered protective boards with lettering in red and in black on the spine. Montval laid paper-covered slip-case with a lithograph on the covers and spine. On Montval laid.

References

B. Baer, Picasso the Printmaker, Dallas 1983.

P. Cramer, Pablo Picasso. The Illustrated Books: Catalogue Raisonné, Geneva 1983.

F. B. Deknatel, “A Lost Portrait of Max Jacob by Picasso,” Annual Report (Fogg Art Museum), No. 1972/1974 (1972-1974): 37-42.

D. Wye, A Picasso Portfolio, New York 2010.

How to cite this information

Julia Stimac, "Pablo Picasso and Max Jacob," 13 November 2019, www.prphbooks.com/blog/picassoandjacob. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.