The Lyonnais counterfeit of the 1501 Aldine Petrarch

The Lyonnais counterfeit of the 1501 Aldine Petrarch.

Petrarca, Francesco (1304-1374). Le cose vulgari di Messer Francesco Petrarcha. [Lyon, ca. 1502].

See the complete description here.

The Lyonnais counterfeit edition of the widely celebrated Petrarca printed by Aldo Manuzio in Venice in 1501 represents an ideal starting point for investigations into the book market and its commercial connections during the early years of the sixteenth century, in the wake of Aldo’s revolution of the printing tradition.

Importantly, the closely contemporary Lyonnais piracy represents the first appearance in print of Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374) in France, and significantly contributed to the growth of the poet’s popularity outside of Italy. The first ‘true’ French Petrarch would only be published in 1545.

From this perspective, the illicit production may also be regarded as a sort of publishing gambit: it was certainly more risky than replicas of classical works, and it responded to the great demand of what was then a diverse and receptive audience, so much so that the Lyonnais piracies were actually reprinted more frequently, and were possibly also more widely sold, than the original Aldine versions.

However, as with the other Lyonnais counterfeits, it is not possible to reduce the present edition to a mere ‘duplicate’ of the Venetian original; rather, such counterfeits must be considered in their own right as a fundamental part of the Aldine phenomenon or vogue, the result of an unprecedented ‘market analysis’, and an essential piece for tracing the European spread of Italian Latin humanism and the italic type (see A. Nuovo. “Transferring humanism: The edition of Vitruvius by Lucimborgo de Gabiano (Lyon 1523)”, G. Proot (ed.), Lux Librorum. Essays on books and history for Chris Coppens, Mechelen 2018, pp. 17-37).

The Lyonnais counterfeit of the 1501 Aldine Petrarch.

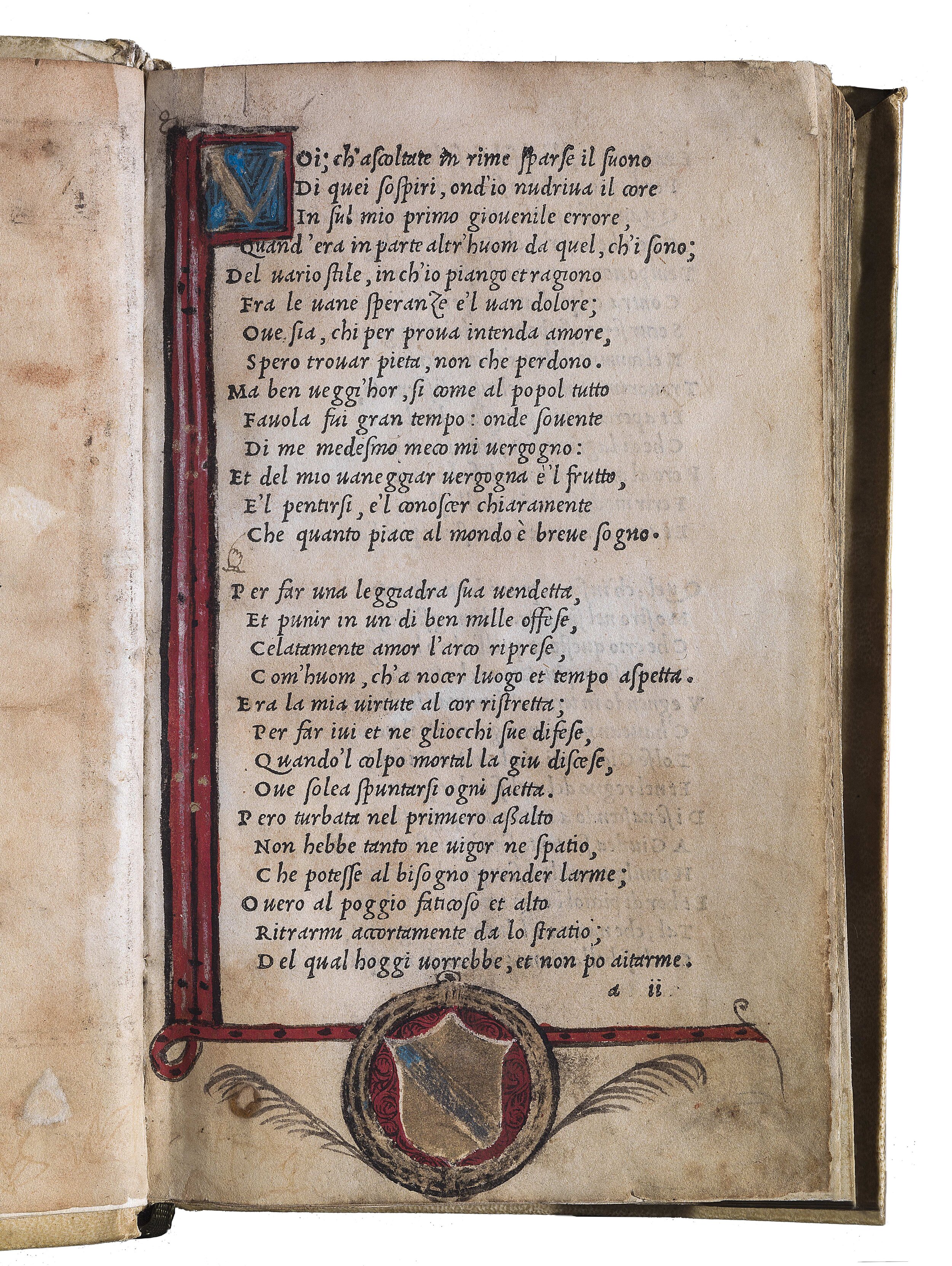

Petrarch’s collection of Italian poems – including the Canzoniere (or, as the poet himself referred to them, the Rerum vulgarium fragmenta) and the Trionfi – was the first of Manuzio’s vernacular books to be set in italic type when it came to light in July 1501 ‘nelle case d’Aldo Romano’. In 1501, Aldo Manuzio revolutionized book printing with his libri portatiles in formam Enchiridii: classical texts issued in the highly portable octavo size and printed in a small new italic type that was highly praised by Erasmus of Rotterdam for its clarity and legibility. The series was inaugurated with the celebrated edition of Virgil, printed in April 1501, which was soon followed by editions of Horace (May 1501), Juvenal (August 1501), and other Greek and Latin writers.

In addition to such classical authors, Aldo included two masterpieces of Italian literature in the new pocket-sized series: Le cose volgari di Messer Francesco Petrarca and Dante’s Commedia, untraditionally titled Le Terze rime di Dante, which appeared in August 1502, and whose publication had been announced by the printer in his postscript to Petrarch. This choice proved to be revolutionary as well: for the first time two Italian vernacular writers were elevated to classical heights. Their works were, furthermore, edited with the same degree of care and scrupulousness, thus laying the foundations of Italian philology. Both editions were edited for Manuzio by the Venetian patrician and humanist Pietro Bembo (1470-1547), who – for the first time in the history of philology – based his editorial work on the collation of different manuscripts rather than on the authority of a single codex, as had previously been the case.

As with other famous – or, from Aldus’ perspective, notorious – unauthorized copies of his octavo editions, the daring counterfeit presented here was realized at the initiative of one of the most astute and active group of merchants of the period: the de Gabiano family.

Originally named Lanza, the de Gabiano took their toponymic from a small village in Piedmont strategically placed between Venice and Lyon, cities where the family’s presence is documented since 1485.

Balthasar de Gabiano – who was in fact responsible for producing the counterfeit Aldines – had been active in the book business since 1493. In Lyon, he represented the Venetian booksellers’ partnership Compagnie d’Ivry, founded by his uncle Giovanni Bartolomeo along with Lorenzo Aliprandi. Balthasar founded his own shop in 1497 in rue Pépin, where he worked until 1517, at which point he returned to his hometown Asti, in Piedmont, to spend the last two years of life as a publishing financier (see H. G. Fletcher. New Aldine Studies. San Francisco 1988, p. 92).

The relationship between the Venetian and the Lyonnais branches of the Gabiano family is still not fully understood despite the numerous extant documentary sources that were thoroughly studied by Henri Braudier in his Bibliographie lyonnaise (Lyon 1895-1921). More recently Corrado Marciani published forty-six Venetian documents that, despite postdating Balthasar’s death, confirm the leading role of the Venetian motherhouse as the primary source for directives and workforce (see C. Marciani, “I Gabiano, librai francesi del XVI secolo”, La Bibliofilia, 74, 1972, pp. 191-213).

The original Aldine Petrarch of 1501.

This copy, presented in the 2016 catalogue Raccolta di Edizioni dantesche, n. 61, is now sold.

In layout and content, the counterfeit Petrarch is nearly identical to the genuine Venetian edition, although the Lyonnais replica lacks Aldus’ address to the reader, the errata, and more importantly the colophon bearing the printer’s name.

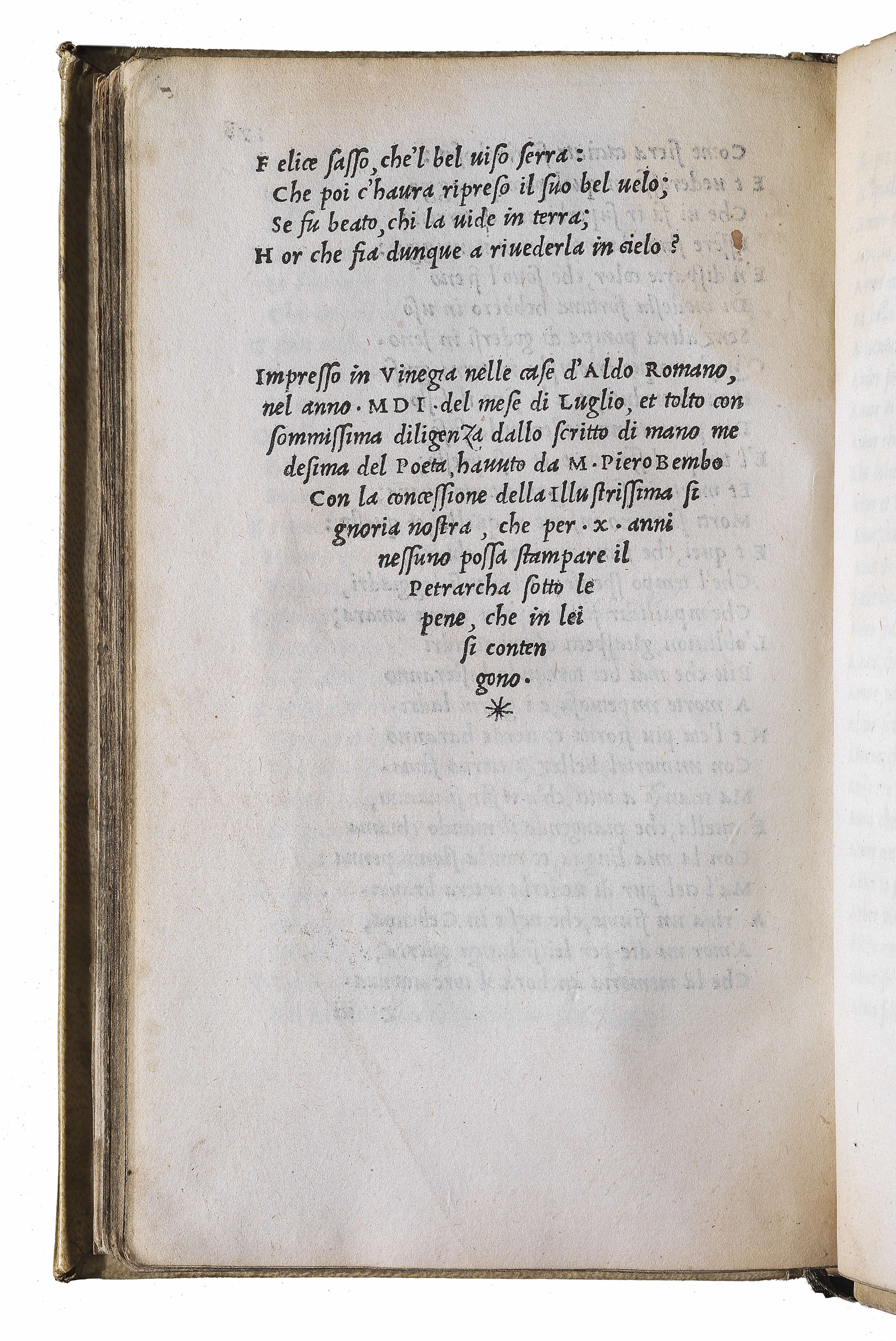

The colophon in the new Aldine octavo editions is of particular interest, representing a link to the emergence of a new requirement against plagiarism and illicit competition inaugurated by Aldus’ bestsellers. Its absence in the French counterfeits thus constitutes a clue for further investigations into the commercial connections of de Gabiano’s Lyonnais printing house.

Since the preparation of the Virgil edition, the potential for the innovatory octavo format – which until then had been reserved to religious works – was immediately evident: easily portable books at cheaper prices made classical texts available to a wider audience, whereas the modern and elegant italic type designed and cut by the talented Bolognese punch-cutter and type-founder Francesco Griffo (1450-1518) would guarantee their collection. Legend held that the type was similar to Petrarch’s own handwriting, the result of a misunderstanding of the 1501 colophon, which states that the text was edited on the basis of a manuscript held by Bembo himself and written in the poet’s own hand. The model of the Aldine italic has also been linked to other distinguished hands, including those of the humanist Pomponio Leti and the renowned scribe Bartolomeo Sanvito.

Despite such discussions of a possible template, Aldus considered this new type an ‘invention’ of his own printing press, just like any other technological novelties introduced in Venice at that age. It is therefore not surprising that in March 1501 he asked the Venetian Senate to protect the new pocket-sized volumes and the innovative typeface, ultimately receiving a ten-year privilege, as recorded in the colophon of his vernacular Petrarch.

Colophon from the original Aldine Petrarch of 1501.

In a second petition against counterfeits dated 18 October 1502, Aldus addressed the Senate once again, this time denouncing illicit editions of his books in Brescia and the production of counterfeited types destined to Lyon. The territorial limit on the monopoly granted by the Venetian Senate made the French counterfeits perfectly legal. The ineffectiveness of this system of book privileges induced Aldus, exasperated by the loss of money and damage to his reputation, to change strategies and turn directly to his public: on 16 March 1503 he printed a broadside titled Monitum in Lugdunenses typographos, a warning against the Lyonnais typographers and their piracies:

“Now from Lyon (as far as I know) editions have been printed with lettering very similar to our own [...] But on all of these you will find neither the name of the printer, nor the place [...] nor the date”.

In the broadside, Aldus explained how to distinguish the counterfeits from his genuine editions: apart from the omission of the colophon, he stated that the Lyonnais counterfeits could be identified by the inferior quality of the paper, the heaviness of the types, the lack of ligatures, and the numerous errors in the text.

If the inaccuracies of the non-authorized editions mentioned in Aldus’ Monitum (Virgil, Horace, Juvenal with Persius, Martial, Lucan, Catullus with Tibullus and Propertius, and Terence) would seem to confirm Aldus’ criticism, the present Petrarch edition presents another story; on the contrary, according to bibliographies, this counterfeit is generally deemed to be an excellent edition, superior even to the Venetian original.

Only a few mistakes, or misprints are in fact detectable. For one, the general title on fol. a1r reads ‘le cose vvlgari’ in place of the original ‘le cose volgari’.

Only a slight variation exists in the titling between the 1502 Lyonnais counterfeit (left) and the original Aldine Petrarch of 1501 (right).

Further, the divisional title on fol. a1v is printed as ‘sonetti et canzone in vita di madonna lavra’ and not correctly as ‘sonetti et canzoni… in vita di madonna lavra’, while the Aldine divisional title ‘sonetti et canzoni in morte di madonna lavra’ on fol. n3v became, in the Lyonnais counterfeit, ‘sonetti et canzoni in morte di madona lavra’.

Alighieri, Dante (1265-1321). La Comedia di Dante Aligieri con la nova espositione di Alessandro Vellutello.... Venice, Francesco Marcolini, June 1544.

According to David J. Shaw, two issues of the vernacular Petrarch were printed in Lyon around 1502 and 1508, respectively. The present copy is in the first issue, datable to 1502. Along with a different number of leaves comprising the volume, this early state is notably represented by the Provençal verse ‘Dreç 7 [i.e. ‘et’] rayson es quieu ciant em demori’ printed on fol. d6v (Sonetto 70, Lasso me, ch’i non so in qual parte pieghi), which here faithfully adheres to the original taken from troubadour tradition. The later counterfeit datable to 1508, meanwhile, shows an evident process of textual Gallicization with the same verse transformed, or better translated, into French as “Droit et raison es que Ie chante damor”. It is especially noteworthy that the Lucchese Alessandro Vellutello (b. 1473) adopted this French ‘translation’ of the Provençal verse for his successful edition of Petrarch supplemented with his commentary – Le volgari opere del Petrarca con la esposizione di Alessandro Vellutello da Lucca, first issued by the Nicolini da Sabbio brothers in Venice in 1525. Thus, Vellutello, one of the foremost exegetes of Petrarch in the sixteenth century and well known for his commentary to Dante’s Commedia printed in 1544 (see a complete description of a copy of this work once owned by Marcus Fugger here), based his editorial work not on the original Aldine, but rather the Lyonnais counterfeit of 1508 (on this see C. Pulsoni, ‘I classici italiani di Aldo Manuzio e le loro contraffazioni lionesi’, Critica del testo, 5, 2002, pp. 477-487, esp. pp. 483-484). This would seem to confirm William Kemp’s hypothesis that the Lyonnais ‘pseudo-Aldines’ or ’quasi-Aldines’ were not uniquely intended for the French market, but were in fact widely circulated throughout Europe.

Binding for the available copy of the Lyonnais counterfeit.

A substantial number of the counterfeits may therefore have been shipped to Italy and traded there with impunity, being issued entirely anonymously and without date. Shaw lists numerous copies enriched with handsome illuminations executed by Italian, or even more specifically Venetian artists, housed in nice contemporary bindings tooled in Italian style, or bearing early Italian ownership inscriptions (see W. Kemp. ‘Counterfeit Aldine and Italic-Letter Edition Printed in Lyons 1502-1510: Early Diffusion in Italy and France’. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada, 35, 1997, pp. 75-100), thus suggesting that the distribution of these pirated Aldines was especially widespread in Milan and in Rome.

The copy presented here of the Lyonnais Le cose volgari di Messer Francesco Petrarca offers further evidence for Kemp’s suggestion, having evidently circulated in the Papal city. The earliest known owner was a certain Alessandro Grassi, who wrote his name on the first leaf.

The second ownership inscription, written on the front pastedown by John Barker, offers further details: ‘Roma, 15. d’Apr-1671. di Sig.r Ales. Grassi, incontro il palazzo del Gouernatore’. John Barker had purchased the counterfeited Petrarch in Rome on 15 April 1671 from Grassi.

The British Library preserves a miscellany that contains four Italian – and primarily Roman – seventeenth-century editions of plays that likewise bears the ownership inscription of John Barker, likewise written in Rome.

Excerpts from “Some English, Welsh, Scottish, and Irish Book-Collectors in Italy, 1467-1850” by Dennis E. Rhodes, included in the 1994 collection of essays in honour of A. Hobson (D. E. Rhodes ed., Bookbindings & Other Bibliophily. Essays in Honour of Anthony Hobson, Verona 1994, pp. 247-276).

This information comes from the paper “Some English, Welsh, Scottish, and Irish Book-Collectors in Italy, 1467-1850” by Dennis E. Rhodes, which was included in the 1994 collection of essays in honour of A. Hobson (D. E. Rhodes ed., Bookbindings & Other Bibliophily. Essays in Honour of Anthony Hobson, Verona 1994, pp. 247-276). Evidently, John Barker belonged to the group of Englishmen who “flocked to Italy in large number”, and more precisely to the “gentlemen on the Grand Tour, which began in the seventeenth century” (ibid., p. 247). Rome was one of the favorite stops in this cultural journey, and Barker sojourned there for several months, at least between November 1670 and April or July 1671, according to his own inscriptions in both the miscellany of the British Library and this Lyonnais Petrarch.

Many issues remain open to discussion: who really was John Barker? Did Barker buy other books in Rome? The possession of the ‘quasi-Aldine’ Petrarch reveals his special collecting taste: did he own other Aldines, no matter their level of authenticity, either genuine or counterfeited? And who was Alessandro Grassi? A Roman collector, or a merchant located near the Palace of the Governatore? Clearly, this ownership inscription deserves further research. However, for the moment we are pleased to pay homage to the unforgettable Dennis Rhodes by finding another book (and what a book!) that once belonged to the curious John Barker.

John Barker’s ownership inscription in the Lyonnais counterfeit.

How to cite this information

Francesca Biffi, “The Lyonnais counterfeit of the 1501 Aldine Petrarch” PRPH Books, 20 May 2020, https://www.prphbooks.com/blog/petrarch-counterfeit. Accessed [date].This post is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

![The Lyonnais counterfeit of the 1501 Aldine Petrarch.Petrarca, Francesco (1304-1374). Le cose vulgari di Messer Francesco Petrarcha. [Lyon, ca. 1502].See the complete description here.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c748f03aadd346d92d68bd1/1589955031203-HHHTXTSNPKN6LNGTSHLZ/petrarch+1.jpg)